Online screening, 27 August-6 September 2021

I was booked to cross the Tasman to see Royal New Zealand Ballet’s recent double bill program, The Firebird and Paquita, but the pandemic got in the way yet again. So I was pleased that a stream of Firebird was available, filmed in Wellington on its opening night there on 28 July 2021.

This Firebird was commissioned from Loughlan Prior, choreographer in residence with Royal New Zealand Ballet, and, while Prior used the music of Igor Stravinsky, familiar to many dance audiences, what resulted was a unique take on the story rather than what many might expect from a production named The Firebird. In essence, Prior’s Firebird is about hope in a world plagued by environmental crises and other chaotic matters, and the Firebird is portrayed as a phoenix-like character who gives hope as she rises from the ashes of destruction.

For most of the time the setting is grim and dark and seems mostly to take place in a run down corner of a harbour town where, in the background, we can see the remains of a ship and a gangplank or two that give the upstage area some height. This world is populated by two groups of people, the Wastelanders who work to survive in harsh conditions and the Scavengers who are constantly and sometimes unpleasantly on the lookout for food and water. Occasionally the scene shifts from a corner of this settlement to a forest-like area (no trees, just scrims and darkness) where the search for food and water takes place. The main figure among the Wastelanders is Arrow (Harrison James). He is without water and falls asleep in the forest area where he is discovered by the Firebird (Ana Gallardo Lobaina). After their encounter she gives him a feather, plucked from her body: it is capable of drawing up water from the depths of the earth.

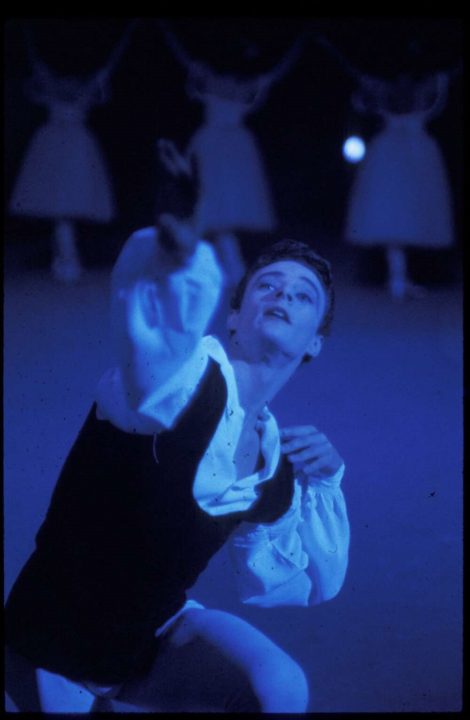

But later the Firebird is captured by the Scavengers, led by the Burnt Mask (Paul Mathews) and his partner Elizaveta (Kirby Selchow). The Firebird is eventually released by Arrow’s partner, Neve (Sara Garbowski), but, angry at having been captured, the Firebird calls on the dark side of her powers to create an inferno that initially engulfs the harbour settlement. Then, drawing on her last remaining strength, she extinguishes the inferno and collapses into Arrow’s arms. Her body bursts into flames. But from the ashes she is reborn and hope fills the world.

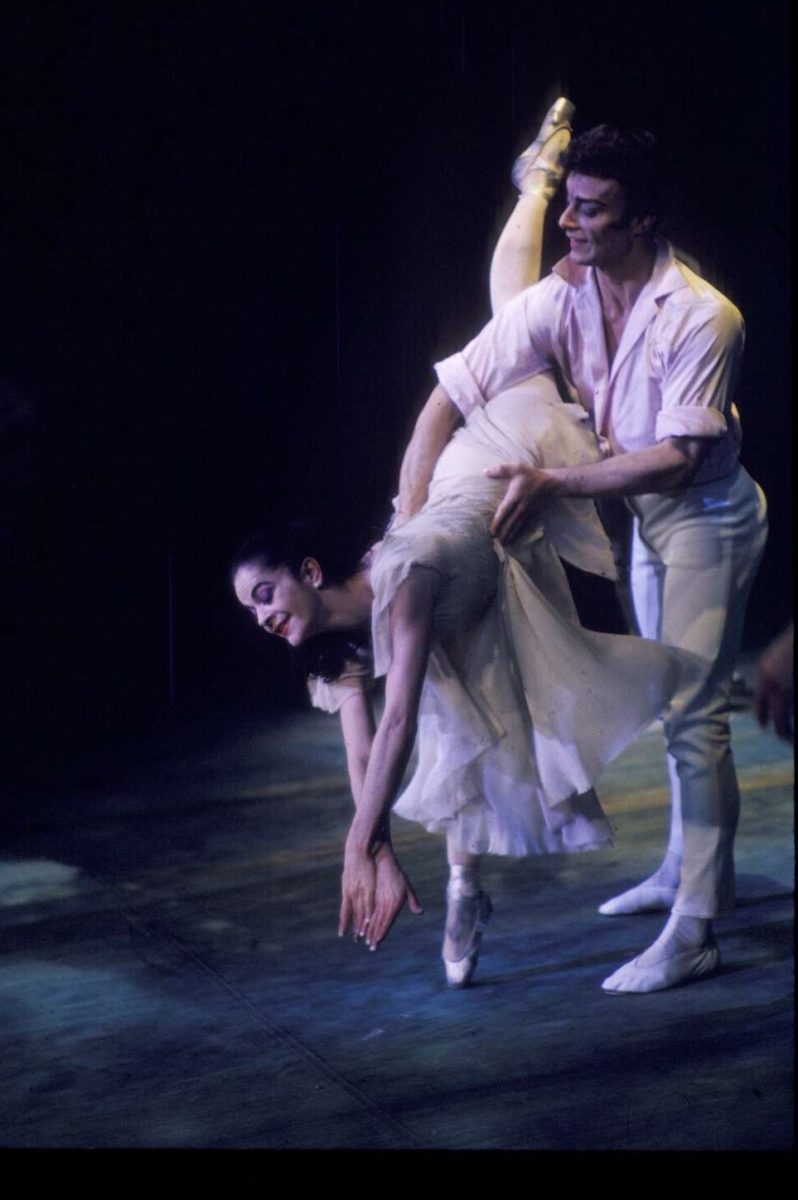

Ana Gallardo Lobaina’s performance as the Firebird is an absolute standout, as is Prior’s choreography for her. At times, especially in her first solo, her movement is quite grounded, but at other times her arms have such a beautiful, lyrical quality, and the way she moves her neck and head tells us so much about her character. Her various pas de deux with Arrow are filled yet again with swirlingly beautiful arms and exceptional lifts. The duet after their first encounter is especially interesting. Harrison James’ performance here is at first hesitant and anxious; he is unsure of how to react to the creature he has just encountered. But he shows growing pleasure in the meeting and we see those changes of emotion quite clearly in the choreography and the performance of it.

Another choreographic highlight is the manner in which Prior develops the idea of the inferno that the Firebird creates. Four dancers surround her and support her as she storms her way around the stage, and at times they gather around her in poses that extend her arms so her wing span looks huge and confronting. Lobaina’s death throes are also beautifully structured and performed, as is her rebirth at the end of the work.

There were one or two moments that I thought needed some extra work from Prior. These were times when groups of dancers stood around watching the main events. Often they appeared not to be involved in the action taking place before them and they reminded me of the young ladies of the village in some productions of Giselle who stand around admiring each other’s dresses rather than being involved in the downstage action. On the other hand, the final group dance as the Firebird was reborn was great to watch with everyone joining in the spreading joy.

I was not a fan of some of Tracy Grant Lord’s costumes, in particular the ‘dropped crotch’ pants worn by many of the characters. While such clothes are something of a fashion item these days, they just look daggy to me, although I guess that added to the shabby look (no doubt intentional) that distinguished those characters and the roles they were playing. The costume for the Firebird, however, was quite spectacular in colour, fabric and cut.

I was blown away by Jon Buswell’s lighting and the exceptional use of visuals and animation from POW Studios, including the orange-red flame and sparkling red spots of light that preceded the comings and goings of the Firebird. Then there were the images of water covering the stage and the crashing waves that appeared in the background as chaos began to rage through the settlement. And, after the incendiary red orb, the darkness and the clouded sky behind the ruined ship that made up the main part of the set, the arrival of the light was quietly beautiful, especially the huge, softly-petalled pink flower that replaced the darkness of the sky.

In the end this Firebird has to be seen as an outstanding example of collaborative input from an exceptional team of creative artists. I can’t help wondering if the kind of visual additions of a technological kind that we saw in this Firebird is the way forward. I have seen similar uses of technology by contemporary companies in Australia (Sydney Dance Company springs to mind) but ballet companies often seem to be a little more set in their ways, especially in large-scale narrative works lasting two or more hours, which may not be surprising. But let’s keep moving.

Michelle Potter, 29 August 2021

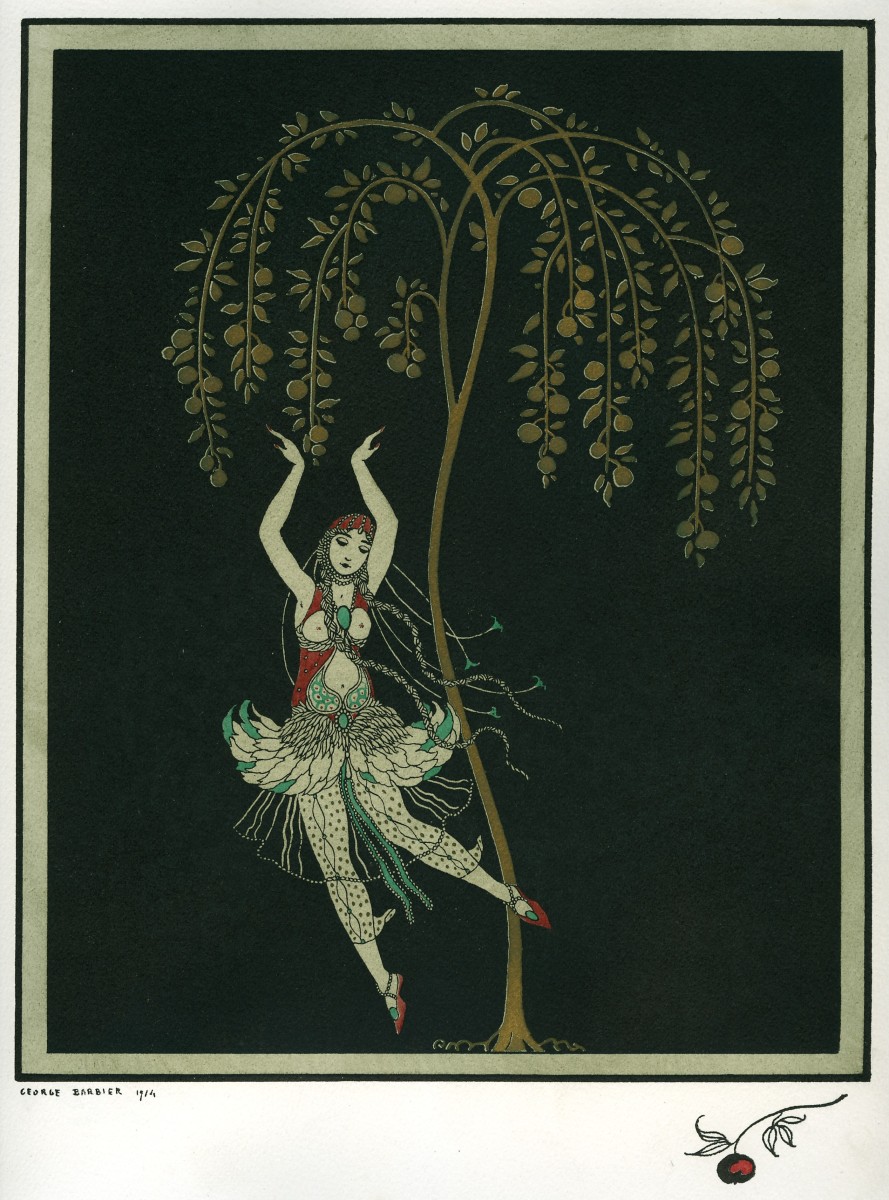

Featured image: The Firebird, Royal New Zealand Ballet, 2021. Photo: © Stephen A’Court