- The Johnston Collection. On Kristian Fredrikson

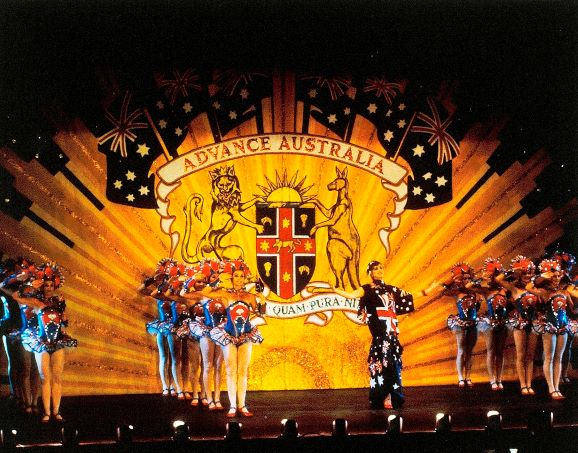

My talk for Melbourne’s Johnston Collection, Kristian Fredrikson. Theatre Designer Extraordinaire, will finally take place on 22 June 2022 just one year later than scheduled. No need, I am sure, to give a reason for its earlier cancellation. I am very much looking forward to presenting this talk, which will include short extracts from some of the film productions for which Fredrikson created designs, including Undercover, which tells the story of the founding of the Berlei undergarment brand.

Further information about the talk is at this link: The Johnston Collection: What’s On.

- Australian Ballet News

The Australian Ballet has announced a number of changes to its performing and administrative team. In May, at the end of the company’s Sydney season, ten dancers were promoted:

Jill Ogai from Soloist to Senior Artist

Nathan Brook from Soloist to Senior Artist

Imogen Chapman Soloist to Senior Artist

Rina Nemoto from Soloist to Senior Artist

Lucien Xu from Coryphée to Soloist

Mason Lovegrove from Coryphée to Soloist

Luke Marchant from Coryphée to Soloist

Katherine Sonnekus from Corps de Ballet to Coryphée

Aya Watanabe from Corps de Ballet to Coryphée

George-Murray Nightingale from Corps de Ballet to Coryphée

In administrative news, the chairman of the board of the Australian Ballet has announced that Libby Christie, the company’s Executive Director, will step down from the position at the end of 2022, after a tenure of close to ten years.

But the Australian Ballet will also face a difficult time in 2024 when the State Theatre at the Arts Centre in Melbourne, where the Australian Ballet performs over several months, and which it regards really as its home, will close for three years as part of the redevelopment of the arts precinct. Apparently David Hallberg is busy trying to find an alternative theatre in Melbourne. But then the company faced similar difficulties a few years ago in Sydney when the Opera Theatre of the Sydney Opera House was unavailable as it too went through renovations. It was perhaps less than three years of closure in Sydney but the company survived then and I’m sure it will this time too.

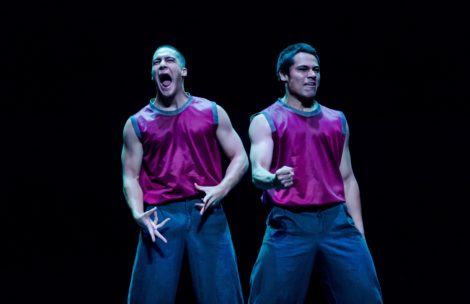

- And from Queensland Ballet

Queensland Ballet’s Jette Parker Young Artists, along with artistic director Li Cunxin, a group of dancers from the main company, and Christian Tátchev from Queensland Ballet Academy, will head to London any day now. The dancers will perform in the Linbury Theatre of the Royal Opera House from 4-6 June as part of a cultural exchange between Australia and the United Kingdom. They will be taking an exciting program of three works under the title of Southern Lights. Those three works are Perfect Strangers by Jack Lister, associate choreographer with Queensland Ballet and a dancer with Australasian Dance Collective; Fallen by Natalie Weir, Queensland Ballet’s resident choreographer; and Appearance of Colour by Loughlan Prior, resident choreographer with Royal New Zealand Ballet.

In addition to the performances, Li will be joined by Royal Ballet director Kevin O’Hare and dancer Leanne Benjamin for an ‘In Conversation’ session, and Tátchev will conduct open classes for dancers from the Royal Ballet School

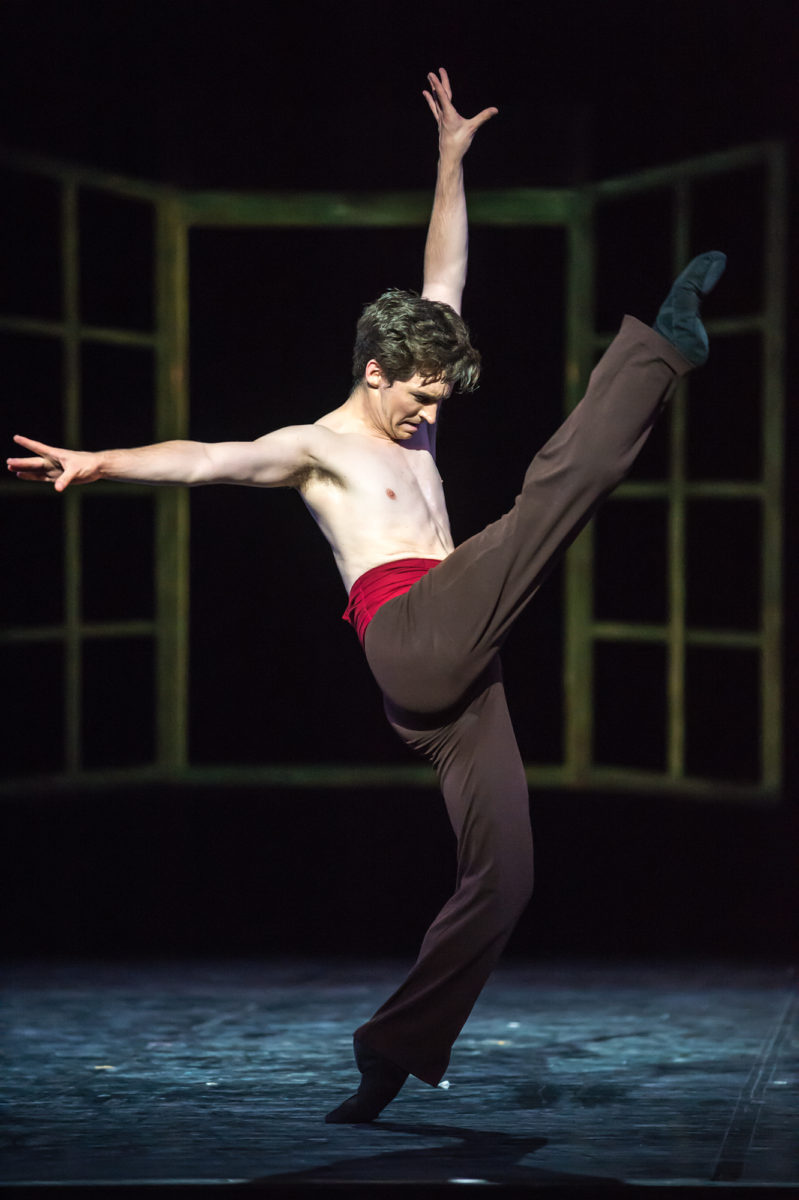

- Not forgetting New Zealand

The Royal New Zealand Ballet has also announced a retirement. Katherine and Joseph Skelton will give their last performance with the company in June. It has been a while since I saw Royal New Zealand Ballet perform live but I have especially strong memories of Joseph Skelton dancing the peasant pas de deux with Bronte Kelly in Giselle in 2016. Both dancers are mentioned in various posts on this website. See Katherine Skelton and Joseph Skelton.

RNZB is filming the pair in the pas de deux from Giselle Act II and the film will be made available on RNZB’s Facebook page on 1 June.

- Street names in Whitlam (a new-ish Canberra suburb)

There has been discussion at various times about naming streets in Canberra suburbs after people who are thought to be distinguished Australians. There was quite recently discussion about abandoning the process completely with complaints being made that the process was not an inclusive one, and that in particular men outnumbered women (along with several other issues). Well not so long ago I joined Julie Dyson and Lauren Honcope in helping the ACT Government select names of those connected with dance to be used as street names in the new-ish suburb of Whitlam. The suburb was named after former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and the decision was to name the streets after figures who had been prominent in the arts (given Whitlam’s strong support of the arts). I looked back at what was eventually chosen (and it was for an initial stage of development of the suburb), and its seems to me that the argument that diversity was lacking is not correct (at least not in this case). The names selected for this stage included men, women, First Nations people, and people known to belong to the LGBTI… community. Some have a lovely ring to them too—Keith Bain Crest, Laurel Martyn View, Arkwookerum Street for example. I’m looking forward to what the next stage will bring.

Michelle Potter, 31 May 2022

Featured image: Still from Undercover, Palm Beach Pictures, 1982