19 september 2009, The Playhouse, Sydney Opera House, Spring Dance

The Oracle, Meryl Tankard’s work set to Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, is a triumph. A solo work for Paul White, who dances with astonishing physicality and intensity, it is an example of how affecting a work can be when the creative team has a strongly shared vision and works single-mindedly to bring that vision into being. The Oracle was visually and choreographically focused and articulate. It moved from section to section as relentlessly as the music until it reached its dramatic conclusion.

Tankard’s choreography, with shared credit to White on the program, moved between small and intricate movements of the hands and fingers and even of the tongue, which required sensitivity of the smallest body part, and movements that demanded that White fling himself through the air, while always maintaining absolute control of the whole body as it hurtled through space. Introverted movements, sometimes executed with the dancer’s back to the audience or with his head shrouded in a chocolate-coloured length of velvety cloth, contrasted with steps of exceptional virtuosity, exuberance and extroversion. Some sections were acrobatic — at one stage White walked on his hands — others had a strong classical feel. This choreography required an extraordinarily versatile performer and White’s performance was quite simply a tour de force.

Tankard assembled The Oracle following the structure of the Stravinsky score but, in her hallmark manner, it was built on multiple layers of meaning and allusion. There were emotive links to Nijinsky, who first gave choreographic expression to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913. They were noticeable in some of the choreographic phrases, which seemed to refer back to Nijinsky’s movement phrases created for his own Rite of Spring. They were also noticeable in those moments when White seemed to be lost in a surreal world, which recalled Nijinsky’s descent into mental illness in the later years of his life. There were allusions to Martha Graham’s well known work, Letter to the World, in which she used her long skirt to give extra shape and form to her choreography. White used that long, chocolate-coloured swathe of velvet not this time to cover his head but as a skirt tied to his waist. He made it swirl through the air as he cart-wheeled and jumped and manipulated it across the floor as he slithered and twisted. The work drew on other sources of inspiration from the work of Norwegian artist Odd Nerdrum to Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman. But The Oracle is absolutely Tankard’s own. One of her great strengths as a choreographer is to make references while maintaining an individual integrity.

Regis Lansac, working again with Tankard as he has done over many years on set and video design, created an opening video sequence to a soundscape of whistling and other mechanical sounds and a recording of Magnificat by the Portuguese composer of the baroque period, João Rodrigues Esteves. This sequence picked up on aspects of the choreography and on images of White and manipulated both to explore a different view of the human body. It seemed also to set up a dance of its own that moved from the figurative to the abstract and back again melding and confusing the two ideas. At times throughout the piece Lansac’s projections and video sequences provided an evocative background. At other times they became essential to the unfolding of the dance, especially in those moments when White encountered his image on the backcloth and needed to contend with what he saw.

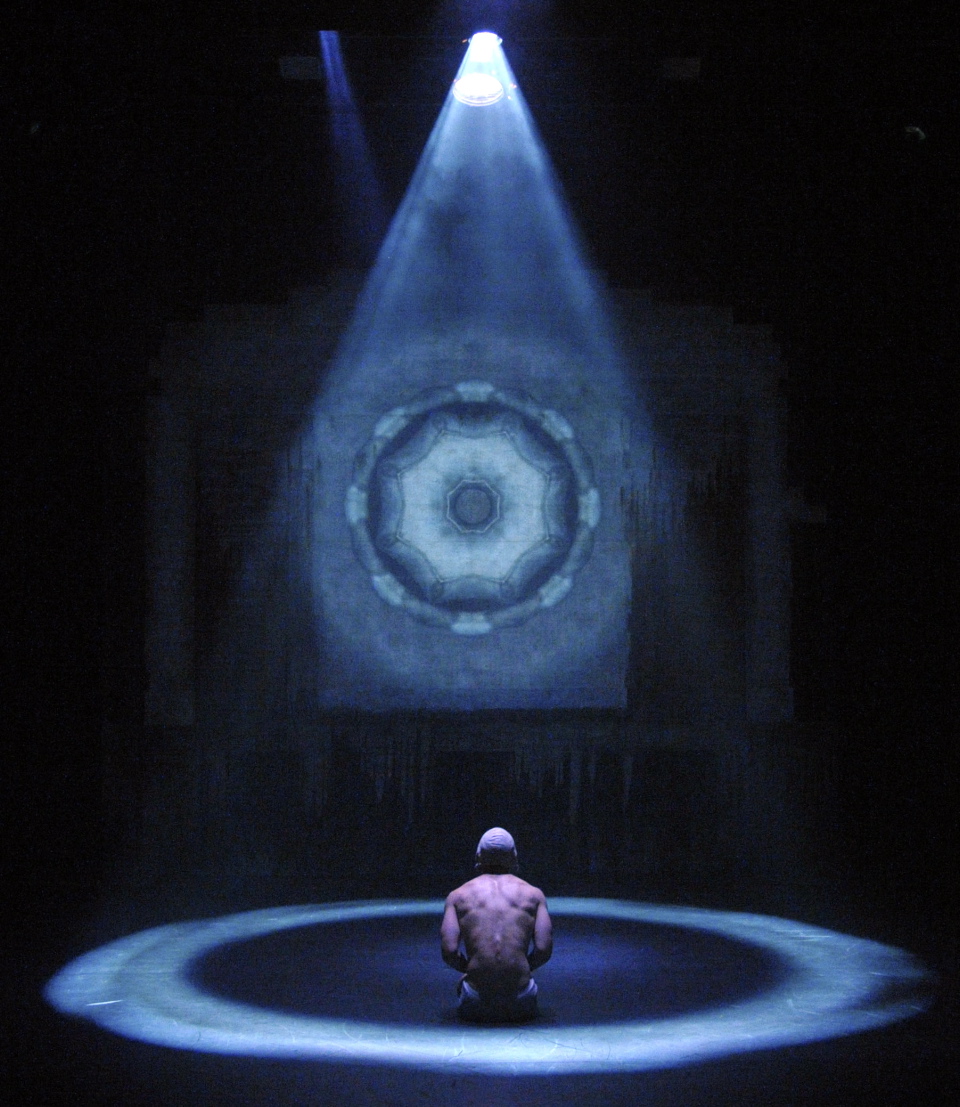

The Oracle was lit by Damien Cooper and Matt Cox. Highlights included the Rembrandt-esque lighting of White’s face, arms and legs in the opening moments; the expanding and contracting circle of light around whose circumference White made a slow and tentative progression; and the breathtaking closing moment as White, centre stage, jumped high into the air as a shaft of brilliant light closed down upon him.

The Oracle shows the collaborative work of Tankard and Lansac at its best. It is an awesome piece of dance and theatre and was received with well deserved shouts of bravo and a standing ovation at both performances I attended.