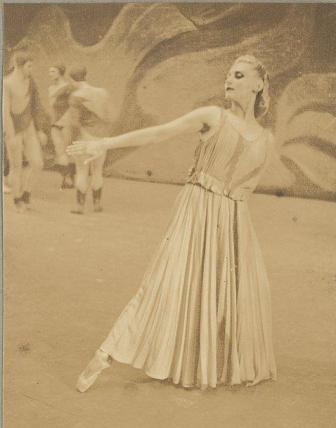

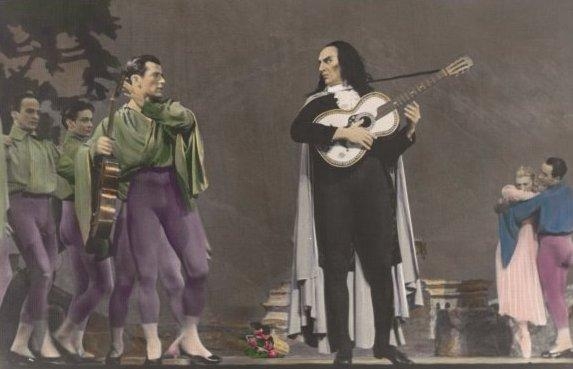

Michel Fokine choreographed and rehearsed his ballet Paganini in Australasia during the 1938-1939 tour by the Covent Garden Russian Ballet. He did not succumb to the suggestion, however, that the ballet be performed in practice clothes so that its world premiere could occur in Australia. He set this decision out in a letter to his friend Sergei Rachmaninoff, to whose music Paganini is set. The letter is reproduced, in part and undated, in Memoirs of a Ballet Master:

‘The ballet was completely choreographed and very well performed in Australia. There was such a demonstration of interest that the management evolved the mad idea of presenting the ballet without costumes and scenery!

Knowing that very often the scenery, and especially the costumes, hamper the dancers, that much that goes well at rehearsals, in practice costumes, gets lost when presented on the stage, I would have welcomed the idea. But in this particular ballet, many dances, if given without the necessary masks and props, without the lighting effects, without the platform, and so on, could not possibly be understood. Therefore I declined this suggestion …’

Paganini was eventually given its Australian premiere in Sydney on 30 December 1939 on the opening night of the third Ballets Russes tour, that by the Original Ballet Russe. This was just six months after the work’s world premiere in London on 30 June 1939. Australian performances of Paganini were foreshadowed by Arnold Haskell writing in 1939 in the Sydney Ure Smith publication Australia. National Journal. Haskell noted that the company was ‘at home’, that is in London, but awaiting a return to Australia. He updated Australian readers on additions to the company and on particular successes achieved during the London season. He reported that Paganini had been ‘the greatest popular success for many years’ but went on to comment that he, personally, was not impressed. He wrote:

‘Its craftsmanship is certain, in one dance set for Riabouchinska, it is vintage Fokine, but the rest seems to have come out of the stockpot of romantic paraphernalia, banished by Fokine himself in “Les Sylphides”. There is the same theme as in Symphonie Fantastique, the battle between good and evil, but it compares to that Ballet as a print from a Victorian Keepsake does to a painting by Jerome Bosch. Soudeikine’s decor greatly detracts. It is at times of a chocolate box sweetness, and the costumes are still worse. Tactful lighting greatly helped here. It is, at any rate, a pleasant spectacle, but somehow I expect more from the Russians.’

Paganini was, nevertheless, also an enormously popular ballet in Australia. It was given 55 performances during seasons in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide. In terms of numbers of performances it was outperformed only by Aurora‘s Wedding (56 performances), Swan Lake Act II (58 performances), and Graduation Ball and Les Sylphides (69 performances each). The initial critical response in Australia was, however, a little lukewarm. The anonymous critic for The Sydney Morning Herald also noted the similarities with Massine’s Symphonie fantastique, and commented that the Massine work was ‘the greater masterpiece by reason of its more elemental, almost seismic release of emotion’. The critic also commented on the orchestral playing noting in particular the impact of the short rehearsal time that had been available to the musicians. But while he (or she) noted that Paganini ‘as a spectacle … provides half an hour of daring, thunderous beauty’ he was unhappy with ‘the obviousness, and at times extravagance, of the symbolism that is employed’.

But perhaps the most interesting interpretation by an Australian came from Bernard Smith. Smith was 23 when he saw Paganini in 1940 and was at the beginning of a long and distinguished career as an art historian and teacher. His interest in the ballet may have been sparked by his interest at the time in surrealism and what he called ‘all the various modernisms’ that were being debated in Sydney art circles. And the Ballets Russes performances certainly offered those interested in these ‘various modernisms’ the opportunity to see first hand examples in the company’s sets and costumes. The repertoire of the Original Ballet Russe as presented in Australia included works with designs by Giorgio de Chirico, Joan Miro, André Masson and Natalia Goncharova, all then at the forefront of one ‘ism’ or another.

Smith was also a friend of Sydney Ure Smith, whose patronage of the Ballets Russes through his various publications is well known, and Peter Bellew, the second husband of Ballets Russes dancer Hélène Kirsova. At the time he was also reading widely from a range of Marxist and other left wing texts and by his own admission was ‘a very active young member of the Communist Party’. Given his artistic and political leanings, then, the tenor of his discussion of Paganini in an unpublished, typescript entitled ‘ “Paganini”, notes after attending the Monte Carlo Diaghilev Ballet in Sydney 1940’ is perhaps predictable. It is, nevertheless, somewhat startling and certainly unique in its point of view. It reads in part:

‘The ballet “Paganini” is one of those works of art which are created to satisfy the “soul-hunger” of the creator or as in this case of the creators. It satisfies a double wish-fulfillment; the desire of the creators, Fokine and Rachmaninoff to hearken back to a Golden Age when there were no class differences and the completely contradictory desire to captivate the hearts (and money) of the bourgeoisie as Paganini did.

The second scene is a feudalist-bourgeois conception of the people, of lovers in an ideal pastoral world, where there are no class barriers … The “people” of the second scene are not the mass of the people at all, they are only the idealised conception of what the bourgeois would look like if they could forget that their own freedom depended upon the slavery of others’.

Smith’s use of the word ‘Diaghilev’ in the name of the company he saw is, of course, erroneous, but his unpublished critique of Paganini offers further evidence that the Ballets Russes visits to Australia inspired a wide range of people working across the arts, and also that they prompted a wide range of responses.

© Michelle Potter, 24 September 2009

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Arnold Haskell, ‘The Covent Garden Russian Ballet’. Australia. National Journal, No. 2, 1939, p. 4.

- “Paganini”, notes after attending the Monte Carlo Diaghilev Ballet in Sydney 1940, unpublished typescript. Papers of Bernard Smith, National Library of Australia, MS 8680 Box 1, Folder 5, Item 5.

- Michel Fokine, Memoirs of a Ballet Master. Trans. Vitale Fokine. Ed. Anatole Chujoy (London: Constable, 1961).

- Oral history interview with Bernard Smith recorded by Hazel de Berg, 20 November 1975. National Library of Australia, TRC 1/888-889.

- ‘Summer: Exhibit A: Bernard Smith—changing the way we see’. Julie Copeland in conversation with Terry Smith and Peter Beilharz. Sunday Morning, Radio National, 22 January 2006. Transcript, accessed 23 January 2009.