Some charming writing about Valentina Blinova, during her engagement with the Monte Carlo Russian Ballet for the company’s Australasian tour of 1936–1937, unexpectedly came to light while I was researching a totally different topic. I came across two typewritten pages, which may have been misfiled by J. C. Williamson Theatres Ltd. as I found them alongside material relating to the promotion by JCW of a Russian ballet tour of a much later date.* It is not clear who wrote the two short articles (Blinova and the JCW publicity team perhaps?), nor whether they were ever published. I have reproduced them below.

A day in the life of a dancing star

A typical day in the life of Valentina Blinova, one of the principal dancers of Colonel de Basil’s Monte Carlo Russian Ballet.

Up at 8.30 in the morning. A cold shower, gymnastics and physical exercises for twenty minutes. A cup of coffee with some toast for “breakfast.” Then a brisk walk to the theatre. Practice. Then rehearsal till quarter to one. Lunch comprising steak or other meat, salad, a sweet, no alcoholic drink, no smoking. Back to the theatre for rehearsal at 2.30 or 3 o’clock until 5.30 or 6. Home for a rest. A cup of tea. Then if she is dancing in the first ballet back at the theatre at 7 o’clock (no dinner). After the performance supper comprising meat, salad and perhaps a glass of Australian wine, which the principals of the Russian Ballet are very fond of. Then to bed.

This is Blinova’s daily routine, the only variation being Sunday which is spent in the open air—in the hills or the bush or on the beach.

And now you know why the members of the Russian Ballet have those slim figures.

How Christmas is spent

Valentina Blinova

Valentina Blinova was born in St Petersburg where she spent her girlhood—at Christmas time her thoughts go back to those days—a gorgeous Christmas tree loaded with candles, nuts, fruits, many sparkling things and presents for all. Christmas Day is regarded as a solemn occasion, not a time for feasting until the evening star is seen in the sky. The children wait longingly for the evening repast—a feast of good things, Then after the presents have been distributed they sit round the fire and seek to pierce the future when other Christmas days shall come. This fortune telling is carried out in a very quaint way. A large piece of wax is melted and thrown into a dish of water and, according to the shadows that are thrown or the shapes the wax takes, so each one interprets their future. But, as Blinova says, it has to be interpreted with a great deal of imagination!

Last Christmas was spent by Blinova in Hamburg, Germany, where she was a member of Leon Woizikowsky’s Company. Christmas was here spent similarly to Russia though the Germans have their own way of celebrating it, which, says Blinova, they do in a very serious way. “We had a Christmas tree,” said Blinova, “but there was the usual performance and when it was over we went to our rooms, where we had supper, and sat around the fire and talked of childhood days in Russia.”

“That was our last Christmas Day. As regards the next:—there will, of course, be no performance. We shall have a party amongst ourselves and, of course, we shall spend most of the day in the beautiful surf on the Sydney beaches.”

Not a great deal of information is available about Blinova’s career, although Kathrine Sorley Walker tells us that she was not trained at the Imperial School in St Petersburg but was ‘the product of a course founded after the Revolution in an attempt to reform teaching methods.’ After her training she went to Germany with Vera Trefilova and Pierre Vladimirov, danced in Monte Carlo, established a partnership with Valentin Froman and came to Australia with de Basil’s company in 1936.

(The story of an apparently spectacular break up with Froman is recounted by Elisabeth Souvorova at this link in one of her letters from Australia.

Michelle Potter, 6 December 2016

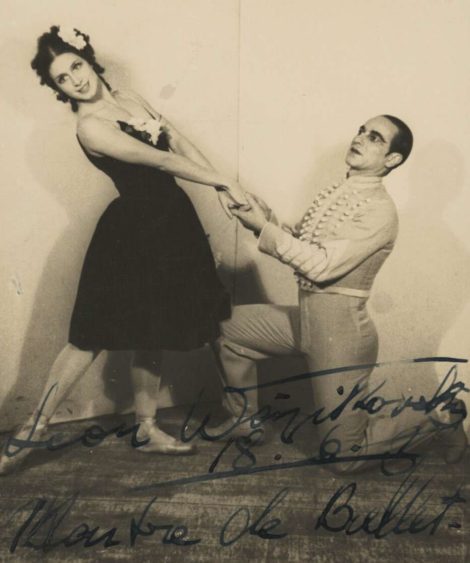

Featured image: Valentina Blinova and Leon Woizikowsky in Le beau Danube, 1936, Bettine Brown Collection, National Library of Australia. Photo: Leicagraph Pty. Ltd., Melbourne. Inscribed: ‘Leon Woizikowsky 18.6.37, Maitre de Ballet’.

* Source: Records of J. C. Williamson, National Library of Australia, MS 5783, Box 353