Dr Ewan Murray-Will (1899-1970) was by profession a dermatologist with a practice in Macquarie Street, Sydney. He studied medicine at Sydney University graduating in 1923 and followed that initial study with further work in Vienna and London. He was honorary dermatologist to a number of Sydney hospitals including Sydney Hospital, St Vincent’s Hospital and the Coast Hospital (later Prince Henry Hospital). Murray-Will also served in World War II in the Middle East and later in North Queensland and was awarded an MBE at the conclusion of the War. He was also a passionate supporter of the arts and a friend and patron of the Ballets Russes dancers who visited Australia between 1936 and 1940.

His home movies documenting performances by, and weekend activities of the dancers of the visiting Ballets Russes companies have been known in Australian dance circles since the late 1990s when they were donated to the National Film and Sound Archive. Some of this remarkable footage was used in The Ballets Russes in Australia: an avalanche of dancing, produced in 1999 by the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Library of Australia. Some was also screened in a compilation of archival footage that accompanied the National Gallery of Australia’s 1999 exhibition of Ballets Russes costumes, From Russia with love.

Perhaps the most engaging of the footage is that shot on Bungan Beach, a beach north of Sydney that even today remains relatively isolated. It is hidden from the main road and accessible only by a walking track. It was at Bungan Beach that Murray-Will regularly rented out a beach house and also regularly invited a number of the dancers to visit on weekends. Much of the beach footage is filmed in slow motion and often shows the dancers demonstrating particular steps or lifts: Paul Petroff seemed to delight in performing grands jetés en tournant the length of the beach and Tamara Toumanova and Petroff enjoyed demonstrating the now well-known ‘presages lift’ from the slow movement of Massine’s Les presages. Other material shows the Ballets Russes dancers performing excerpts from their repertoire. A beautiful clip shows Nina Golovina in a scarlet swimming costume with her long dark hair falling over her shoulders dancing with Anton Vlassoff in an excerpt from the Bluebird pas de deux from Aurora’s Wedding. Some of Murray-Will’s footage, including the ‘Bungan Ballet’ a watery spoof created by four of the dancers, is available online from the National Film and Sound Archive’s australianscreen site:

http://aso.gov.au/titles/home-movies/ballets-russes-de-monte-carlo/

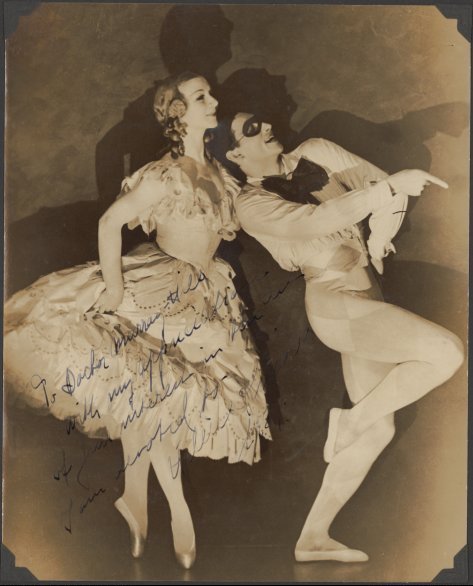

But Ewan Murray-Will also bought art and moved in those Sydney circles where contemporary art was promoted and where both developments in the visual arts and the activities of the Ballets Russes were seen as part of the same attitude to contemporary creative endeavour. Murray-Will was, for example, a friend of publisher and patron of the arts Sydney Ure Smith, as Ure Smith’s collection of letters in the Mitchell Library in Sydney indicates. He was also close to Ballets Russes dancer Hélène Kirsova, whose second husband was Peter Bellew, first secretary of the Sydney branch of the Contemporary Art Society and in part responsible for securing Sidney Nolan’s commission to design Icare for Australian performances by the Original Ballet Russe in 1940. Kirsova autographed to Murray-Will a photograph of her and Igor Youskevitch in Le Carnaval with the words: ‘To Doctor Murray-Will, With my appreciation of your interest in the arts I am devoted to, Helene Kirsova, 1937’.

Ewan Murray-Will’s contribution to our knowledge of the Ballets Russes aesthetic as it was understood in Australia also includes that he collected, and then bequeathed to major institutions, paintings and drawings with a connection to the Ballets Russes. At least two designs by Alexandre Benois for Petrouchka were bequeathed by Murray-Will to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. They are a costume design for ‘Un jeune artisan ivrogne’ (A drunken young workman), a character that perhaps never appeared on stage in productions of Petrouchka, and a set design for ‘La chambre du nègre’ (The Negro’s bedroom), which is a variation on the better-known set for that scene in the ballet.

But perhaps more pertinent in the context of the influence the Ballets Russes had on Australian artists are those items bequeathed to the National Gallery of Australia by Murray-Will that are currently on display in the exhibition Rupert Bunny: artist in Paris at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. They include three oils on canvas painted in Paris between 1913 and 1920: Peleus and Thetis, The prophetic nymphs and Poseidon and Amphitrite. Any Ballets Russes influence on Bunny, best described perhaps as an expatriate Australian, came of course from Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes rather than from the touring companies that Australians saw in the years following Diaghilev’s death in 1929. The colours of Bunny’s palette in all three paintings recall the juxtapositions for which Léon Bakst became famous with his costume and set designs for Diaghilev. And the swirl of Amphitrite’s hair in Poseidon and Amphitrite, which was owned at one stage by Edouard Borovansky, recalls the decorative elements of flowing scarves and other items that feature in Bakst’s costume designs.

The most interesting of the three paintings, however, is Peleus and Thetis and, while Bunny’s colour juxtapositions may be a result of the influence of late nineteenth/early twentieth-century European artists, including Paul Gaugin, rather than, or as well as Baskt, there are nevertheless clear references to the Ballets Russes in this painting. Bunny painted Peleus with her feet and knees turned to the side as if on a frieze. Her body, however, is facing the front although her head is in profile. Such a pose clearly recalls the choreography for the nymphs in Afternoon of a Faun (1912), Vaslav Njinsky’s groundbreaking work for Diaghilev. Moreover, the angular position of Peleus’ arms, especially the way her left elbow is bent into a triangular shape as she resists Thetis’ advances, is similar to the arm positions of Nijinsky and the leading nymph in Faun as the two engage with each other before the nymph drops her scarf and flees. Even the hairstyle of Peleus recalls the wigs worn by the nymphs in the ballet, which closely fitted the head like a skull cap but had long strands of curls emerging at the back from the nape of the neck.

Ewan Murray-Will is reported to have been a reserved man. He left, however, a legacy to the arts world whose significance is probably yet to be fully explored. That legacy is largely a result of his exploits as an amateur filmmaker. But his activities as a collector of paintings and drawings, especially as they elucidate further the activities and aesthetic of the Ballets Russes in Australia and on Australians, are also of significance.

Postscript: Rupert Bunny: artist in Paris is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until 21 February 2010 and then travels to Melbourne and Adelaide.

© Michelle Potter, 27 November 2009

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Australia Dancing. ‘Dr Ewan Murray-Will’ as archived at this link

- Benois, Alexandre-Nikolayevich. ‘Jeune artisan ivrogne’, costume study for Petrouchka, 1936, watercolour, gouache and pen and ink over pencil sketch, 32.2 x 24.8 cm sheet (irreg), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Bequest of Dr Ewan Murray-Will 1971, 11.1971

- Benois, Alexandre-Nikolayevich. ‘The Negro’s Bedroom’, set design for Petrouchka, 1931, drawing, gouache and pen and ink over pencil sketch, 25.3 x 36.2 cm image/sheet, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Bequest of Dr Ewan Murray-Will 1971, 12.1971

- Edwards, Deborah. Rupert Bunny: artist in Paris (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2009).

- Potter, Michelle. ‘Mutual fascination: the Ballets Russes in Australia 1936-1940’. Brolga 11 (December 1999), pp. 7-15.

- Turnbull, Clive. The Art of Rupert Bunny (Sydney: Ure Smith, [1949?])