My review of the latest Chaos Project from QL2 Dance was published online on 19 October by CBR CityNews. Read it at this link. Below is a slightly enlarged version of the review.

The Chaos Project from QL2 Dance has become an annual event on Canberra’s youth and community dance scene: an event that gives young, aspiring dancers an opportunity to experience dance in a theatrical environment and to celebrate dancing on stage with colleagues.

Elemental, the 2024 project, was, however, a little different from previous productions. It was the first Chaos Project directed by Alice Lee Holland, who just recently has taken over the reins of QL2 Dance from Ruth Osborne. Elemental consisted of five separate works. They explored the elements of fire, space, air, earth and water, with each created by a different choreographer, or choreographers in the case of the final work.

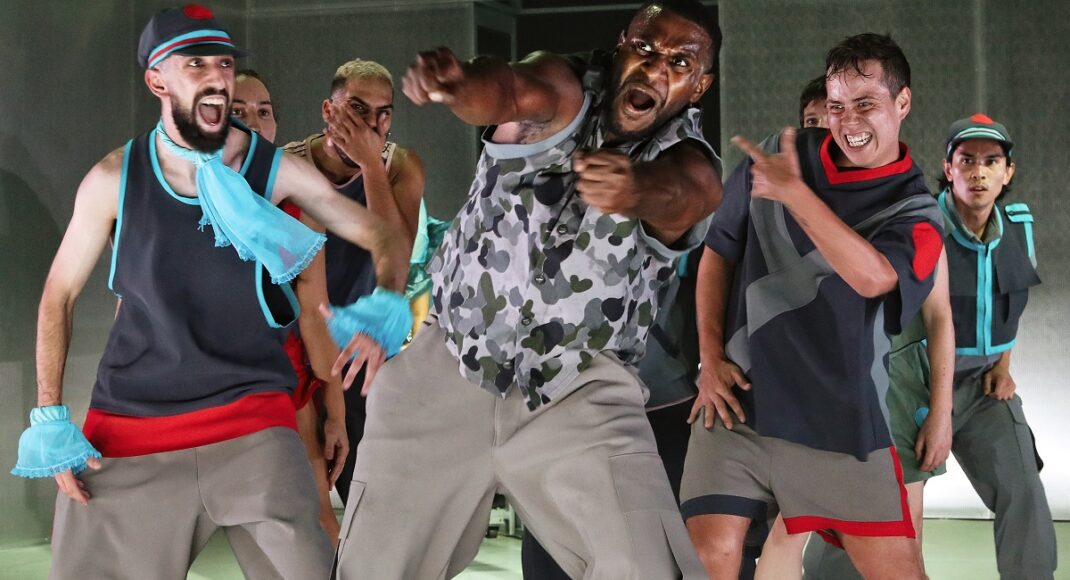

The standout work by far was Earth choreographed by Alice Lee Holland. Although, as is the case with all five sections, the cast (of ten dancers in the case of Earth) was acknowledged as contributing to the choreography, it was Holland’s compositional input that really made the work the standout. Her extensive and varied use of the performing space, and the way she used groupings of dancers and had them interact with each other, meant that the work was always interesting to watch. In addition, her clear and dedicated development of the choreography gave the dancers a strong structure in which to work. Every one of them used their emerging performance skills with admirable courage and power.

The other four works, Fire from Jahna Lugnan, Space from Max Burgess, Air from Jason Pearce, and Water from Lugnan, Burgess and Pearce working together, did not to my mind have the same choreographic strength. All seemed to focus on movement of the arms and hands to the detriment of use of the whole body, and in some cases groupings of dancers seemed somewhat muddled. This was especially noticeable in the final work, Water, which had the largest cast and seemed not to have a strongly focused structure (as a result of having three choreographers working together perhaps?).

Pearce’s Air was something of an exception given that his aim was to explore the role of air on the body and how that aspect of the element can be expressed as a cohesive whole. Arm movements thus, rightly, played a major role, as did the gathering of the dancers in a single group for much of the work. Costumes for Air were quite exceptional. All the performers wore white to reflect an Arctic landscape and, while the colour was unvaried, the actual designs were all different and quite beautiful to look at. Their strength and beauty was, however, best seen without the blue-ish lighting that occasionally flooded over them.

Lighting for Elemental was designed by the individual choreographers. Costume coordination was by Natalie Wade, although it is not clear who actually designed the costumes.

The major difference from previous Chaos Projects was the ending. Gone was a fully choreographed finale as we have become used to seeing—one of Ruth Osborne’s signature additions over the years of her directorship. The production finished, as most dance performances do, with the cast simply taking a curtain call. But, being used to a choreographed finale, I guess a simple curtain call was more of a shock than anything.

It will be interesting to see how the Chaos Project develops in future years under the direction of Alice Lee Holland. Personally, I hope the future may bring stronger choreographic input across the entire production.

On a closing note, I loved the image on the back of the printed program, which I think was created by Millie Eaton. She is acknowledged in the program’s list of the ‘creative & production team’ as doing ‘Program illustrations’. She also appeared in Fire, the work for the youngest members (aged about 8) of Elemental. The image indicated a complete involvement in the production, which is a feature, or certainly the aim, of every Chaos Project.

Michelle Potter, 20 October 2024

Featured image: Dancers from QL2 in a moment from Earth. Photo: Olivia Wikner, O&J Photography