20 February 2020, David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, New York

Liebeslieder Walzer; Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2,

This double bill of works by Balanchine had two highlights for me: Teresa Reichlen’s performance in the leading female role in Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 and that of Wendy Whelan in Liebeslieder Walzer.

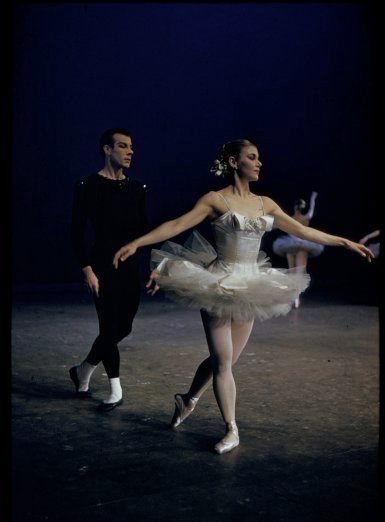

Teresa Reichlen, whom I remember admiring in a variety of solo roles in 2007, was promoted to principal dancer in 2009. Her dancing is still a little coltish but her limbs are beautifully proportioned in relation to her trunk and she is technically self-assured. But more than anything else she is an artist who understands how to maximise her technical ability and physical capacity. Her dancing shows in particular the expansiveness that can characterise balletic movement. In Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto her grands jetés en tournant provided a breathtaking example. Each time we watched this step unfold on stage, as Reichlen thrust the second leg into the air her chest opened, her neck stretched and her head lifted. Here before our eyes was the broadness of scale, the open and communicative nature of classical ballet.

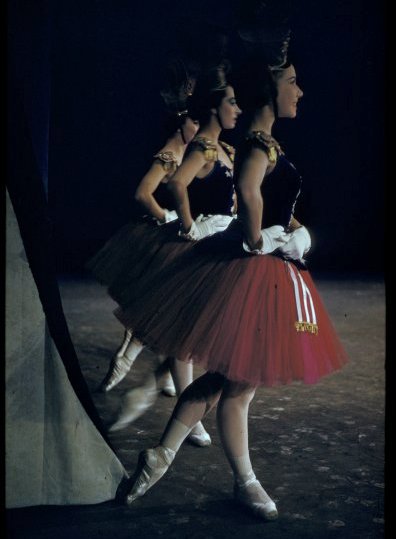

I continue to think, however, that this ballet, which in an earlier manifestation was called Ballet Imperial, would have more impact with the female dancers in tutus, as was earlier the case. Despite any changes that may have been made to the original 1941 version, the ballet is still structurally and in its vocabulary a Petipa-style ballet and begs to be costumed in the Petipa tradition. Those floating chiffon ‘night-dress numbers’ do nothing for it.

Wendy Whelan, in contrast to Reichlen, has been a principal since 1991 and her maturity as a dancer and an artist is clear. But again she is one of those dancers who is able to use technique as a means to an end. Liebeslieder Walzer, like the Tschaikovsky, also contained some breathtaking technical moments. Perhaps the most moving occurred in the very last pas de deux for Whelan and her partner when a series of posé turns by Whelan suddenly and unexpectedly gave way to a promenade in arabesque with her partner deftly moving into place to take Whelan’s hand and lead her into the promenade. The surprise of this movement was of course partly Balanchine at work, but it took Whelan’s fluid dancing to bring it so beautifully to life.

Both Reichlen and Whelan have that knack of showing an audience what artistry is about. They both are able to take ones breath away with what so often in the hands of lesser dancers looks like just another step.

Michelle Potter, 27 February 2010