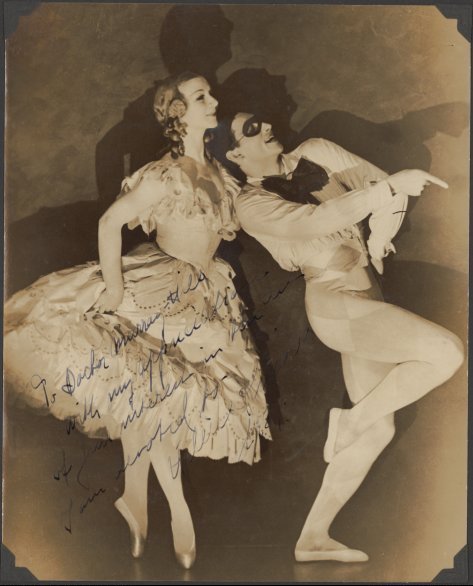

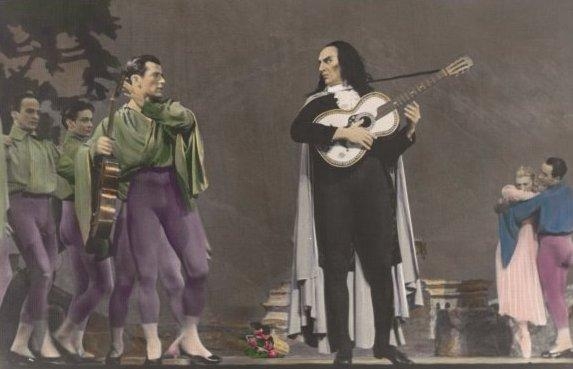

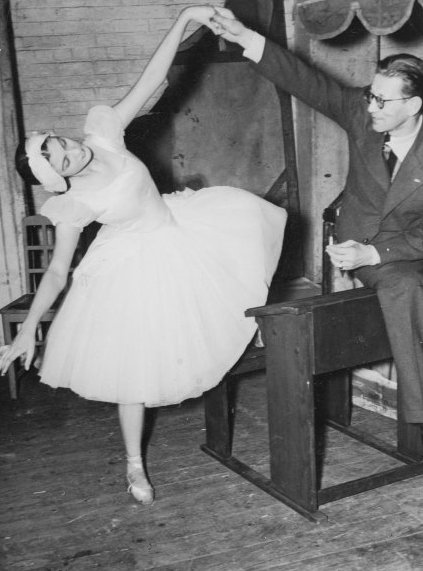

David Lichine choreographed close to fifty ballets during his lifetime. Graduation Ball, which premiered in Sydney on 1 March 1940, was probably his most successful. In Australia, from March to August 1940, the work was given 69 performances by the Original Ballet Russe, a statistic equalled only by one other ballet during the season—Les Sylphides, which also received 69 performances.

Lichine also created a sequel to Graduation Ball, scarcely known, apparently performed only in Argentina, and called Girls’ Dormitory. The Riabouchinska/Lichine papers held by the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts contain a letter from Lichine to the Director-General of the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, dated 13 March 1947, in which Lichine maintains that a sequel was in his mind ‘from the moment the curtain closed on the opening night of “Graduation Ball”‘. According to Anne Robinson, Girls’ Dormitory was planned for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1945, although it was never performed by that company. Its premiere performance was given in Buenos Aires in July 1947 by the Teatro Colón Ballet.

In the same letter to the Director-General Lichine writes ‘The ballet will have many comedy situations … and the corners filled to capacity with youthful abundance of virginal gaiety’, and he notes that the costumes will be similar to those of Graduation Ball. He writes: ‘The boys are all dressed as young cadets and all the girls in uniform with only slight alterations’.

Robinson records that the music for Girls Dormitory was by Offenbach, orchestrated by Antal Dorati, and that the work was designed by Mstislav Dobujinsky. However, a series of designs all dated 1949, clearly entitled ‘Girls Dormitory’ and signed by Alexandre Benois are part of the Manuscripts and Rare Books collection of the Boston Public Library. They appear to be for a different production entirely as the costumes for the girls are chaste night dresses rather than the uniforms mentioned in Lichine’s letter. They are labelled ‘Tenue de nuit de toutes les pensionnaires’. Other designs in the Boston collection are labelled ‘II—Le cauchemar’ and, according to Anna Winestein, in this second act ‘the protagonists find themselves in an exaggerated, nightmarish version of the school they attend’. In his letter to the Director-General Lichine also advises that he is enclosing a synopsis of Girls’ Dormitory but, frustratingly, this synopsis is not included as part of the Riabouchinska/Lichine papers. So the relationship between the ballet Benois designed and what went onstage in Buenos Aires remains unclear.

However, some of the Benois designs in Boston are of interest in the Australian context. Three of these designs are for teachers who appear in the Act II nightmare—’Le Maître de l’Histoire’, ‘Le Maître de Geographie’, and ‘Le Maître de la Grammaire’. While the designs for the professors of Mathematics and Natural History who appeared in the Australian divertissement ‘Mathematics and Natural History Lesson’ (see previous post) have not been located, the Boston designs give an insight into what they may have looked liked. They perhaps also suggest that the idea of the Australian divertissement may have been that of Benois rather than Lichine.

© Michelle Potter, 17 March 2010

Notes:

- Girls’ Dormitory was, according to Robinson, never seen onstage outside of Argentina, although a film combining Graduation Ball and Girls’ Dormitory was made in Mexico in 1961 by Jose Luis Celis.

- The Boston designs are reproduced in Anna Winestein’s Dreamer and showman. The work of Benois is still in copyright and this website is not in a financial position to be able to pay reproduction fees.

Bibliography

- Anne Robinson. ‘The work of dancer and choreographer David Lichine (1910–1972): a chronology of the ballets with a brief critical introduction’, Dance Research, 19 (No. 2, Winter 2001), PP. 7–51

- Anna Winestein. Dreamer and showman. The magical reality of Alexandre Benois (Boston: Boston Public Library, 2005).

- Papers of Alexandre Benois 1913-1959, Boston Public Library, MS 2029

- Papers of David Lichine and Tatiana Riabouchinska (unprocessed), Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts