Cecil Bates had a remarkably diverse career both in and outside of dance. Born into a family in which the arts held a prominent place, he recalled that his first stage experience came at the age of three when, in one of his mother’s ballet concerts, he took the role of a teddy bear.

I first appeared in these shows, I believe, at the age of three, as a teddy bear. I remember being very angry with my mother because she didn’t think that I would know the time to come on to the stage, to know the right cue. But I was perfectly well aware of when to go on and, when she reminded me by giving me a gentle push, I was very angry and almost missed the entrance.1

His mother was a dancer and an operatic soprano. She was a pupil of Melbourne-based teacher Jennie Brenan and appeared in several productions by J. C. Williamson. She taught ballet in Maitland where her son was a pupil until he left primary school.

His father served in World War I and then took up teaching. It was he who convinced Bates to give up ballet once he entered high school and, at the end of his schooling, Bates took up a traineeship in metallurgy. He worked with Rylands Brothers Wire Mills in Newcastle while undertaking a technical college course in metallurgy.

But he was ‘restless’, as he remarked in an oral history interview, and began taking ballet classes in Newcastle with Grace Norman. Then, with a fellow ballet student, he went to Sydney to take a class with Hélène Kirsova and, as a result, moved to Sydney, changed his course to a similar one at Sydney Tech, and began working for Commonwealth Industrial Gas.

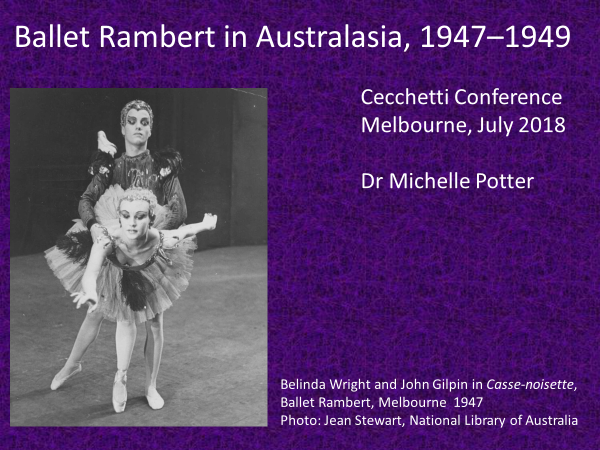

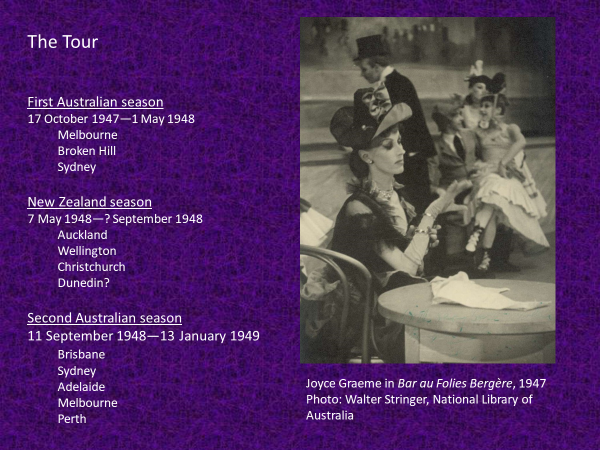

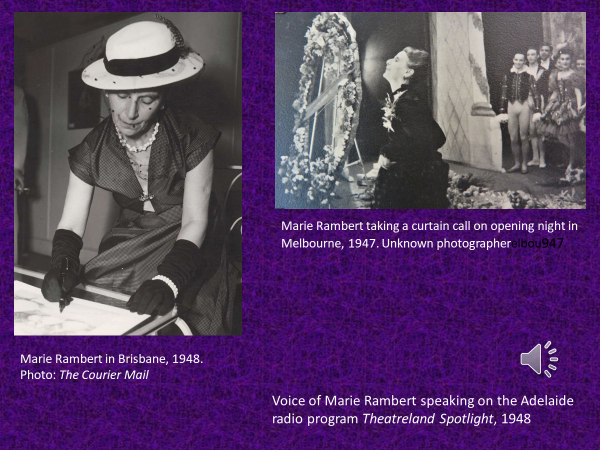

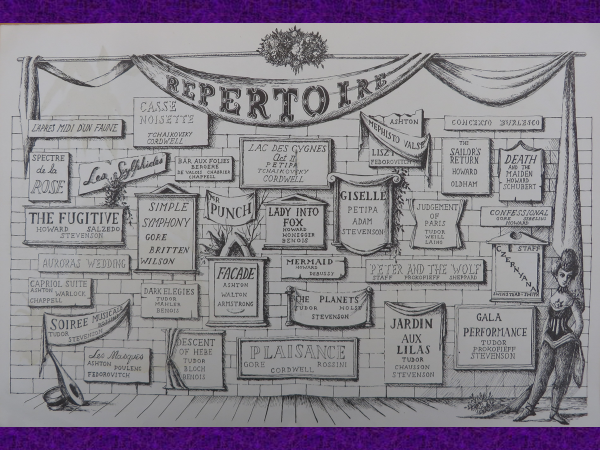

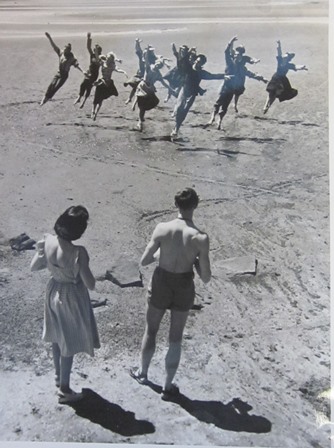

Although Bates didn’t ever dance with the Kirsova Ballet, Kirsova was impressed with his potential and suggested to Marie Rambert that she audition him for the Rambert Australian tour of 1947–1949. Bates joined Ballet Rambert in Melbourne in 1947 where he made his debut as a professional dancer. He toured Australia and New Zealand with Ballet Rambert and, when the company returned to England in 1949, he went with them.

In England he became a principal dancer and later ballet master with Ballet Rambert and then, on leaving the Rambert company in 1953, danced with Walter Gore and in a variety of other productions including pantomime and film. It was during his time in England, encouraged by Marie Rambert, that he began to choreograph. His early choreographic works included two Scottish-themed productions for Rambert’s Ballet Workshop and a new version of Carnival of the Animals for the Rambert company. It was also the time when he took classes from Audrey de Vos, whose impact on his career continued throughout his life.

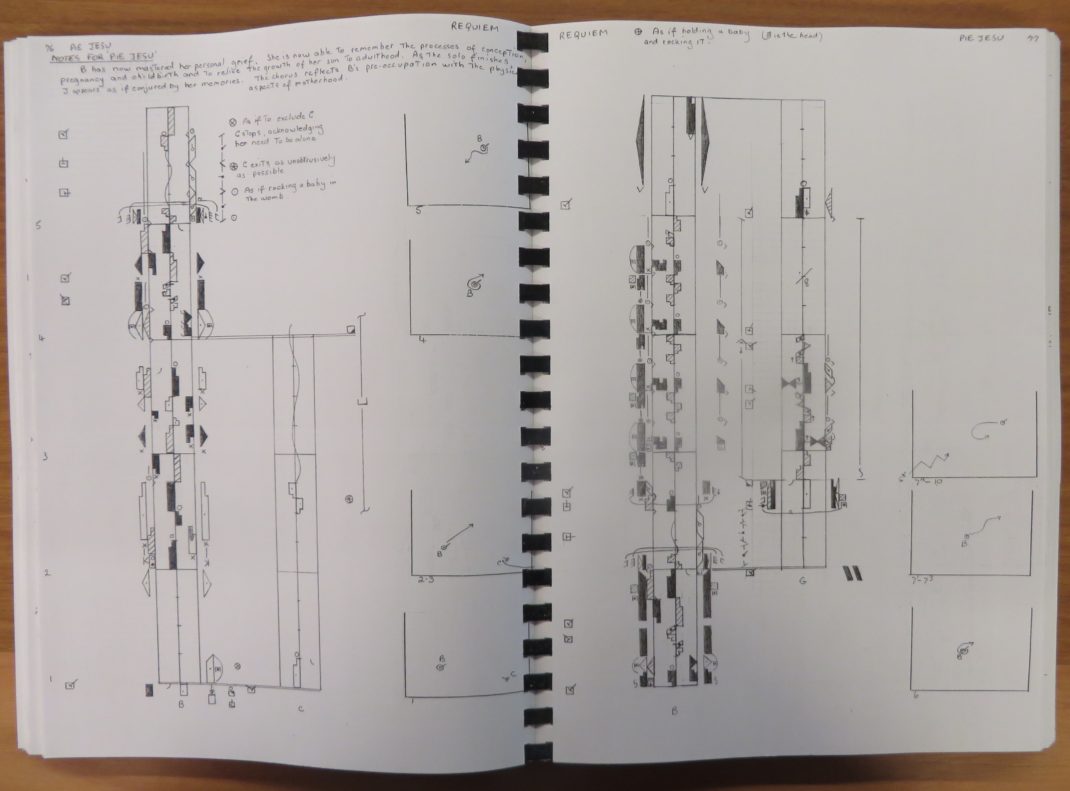

After the breakdown of his 1950 marriage to Rambert dancer Mary Munro, Bates returned to Australia to dance once more with Walter Gore who had set up Australian Theatre Ballet. When Gore’s Australian company folded, Bates went to work with Joanna Priest in Adelaide teaching and producing for her various initiatives and, in 1962, became artistic director of the recently-formed South Australian National Ballet Company. He also returned to choreography producing Design for a Lament (later staged as Requiem and dedicated to his mother, Frieda Bates), Villanelle for Four, Comme ci, comme ça, Seven Dances and A Fig for a King. In Adelaide Bates also staged some of the ballets he knew from his London experiences. They included Peepshow, Death and the Maiden, Czernyana and Façade. He also established his own dance school and then a small company, South Australian Repertory Ballet.

Bates eventually moved into a more academic life and began teaching maths and science, and drama on some occasions, at a series of high schools in Adelaide. He undertook a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English and Economic History at the University of Adelaide.

Bates was also an experienced Laban notator. His interest in notation began in London when he began taking lessons in Laban notation from an ex-dancer from the Kurt Jooss company. It was not, however, until he began working in Adelaide that he resumed his studies in notation, eventually taking a University course in the subject. He notated his own works and works by others with whom he had been associated, including Walter Gore, Andrée Howard, and Joanna Priest. He was later asked by Meg Denton to notate his work Requiem for Denton’s Australian Choreographic Project.2

Bates is survived by his second wife, Glenis, his three children and numerous grandchildren.

Cecil Hugo Bates. Born Maitland, New South Wales, 26 May 1925; died Adelaide, South Australia, 20 December 2019

An oral history interview recorded in Adelaide in 2005 for the National Library of Australia’s Oral History and Folklore Collection, from which much of the information in this obituary has been obtained, is available at this link.

Michelle Potter 3 March 2020

Featured image: Cecil Bates in the pas de trois from Swan Lake (detail), 1940s? Photographer not identified. National Library of Australia, Papers of Cecil Bates, MS 9427

Notes:

1. Oral history interview with Cecil Bates recorded by Meg Denton in 1985. J. D Somerville Oral History Collection, Mortlock Library of South Australiana, OH 84/16. A transcript of this interview is in the National Library of Australia, Papers of Cecil Bates, MS 9427.

2. For more about the Australian Choreographic Project see Meg Abbie Denton, ‘Reviving Lost Works: The Australian Choreographic Project.’ Brolga, 2 (June 1995), pp. 57-69.