A Feast of Wonders: Serge Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes

Edited by John E. Bowlt, Zelfira Tregulova and Nathalie Rosticher Giordano (Milan: Skira, 2009)

In this very handsome volume published in conjunction with the exhibition Étonne-moi: Serge Diaghilev et les Ballets Russes, which opened in Monaco on 9 July 2009, Alexander Schouvaloff has an essay entitled ‘The Diaghilev Legend’. In it he remarks on the ‘continued fascination’ with the Ballets Russes. He writes, ‘It is puzzling. Artifacts and records remain to obsess scholars.’ Well, the contents of this book make his use of the word ‘puzzling’ a puzzling one indeed.

The publication contains, in addition to the Schouvaloff piece, eleven other essays most of which develop their topics in contexts that have not previously been widely examined in the existing English writing on the Ballets Russes. For example, Nicoletta Misler’s ‘Dance, Memory! Tracing Ethnography in Nicholas Roerich’ draws on a wide range of Russian sources to examine Roerich’s use of shamanistic and similar imagery, particularly in his designs for Le Sacre du printemps. Then, Evgenia Iliukhina traces the roles of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova in the Diaghilev enterprise. She notes Goncharova’s sources and the influence of other artists on designs for her major pieces, including those works, such as Liturgie, which were not realised but which nevertheless were significant developments. Iliukhina also looks at Larionov’s interest in choreography and the evolution of his attitude to the role of design in ballet. The article rightly positions Goncharova and Larionov as major artists in the post 1914 period of the Ballets Russes and as more than simply successors to Bakst and Benois.

These articles, and others of equal interest, suggest that the ‘continued fascination’ will last for decades yet, especially when there is still much primary source material awaiting the attention of scholars. Despite the fact that 2009 celebrates the centenary of Diaghilev’s first Ballets Russes season in Paris, it is clear that there is still much to be discovered and written about. And to return to Schouvaloff, if one follows his instructions regarding the ‘Find a grave’ website, which he gives at the end of his piece, it is clear too that Diaghilev’s charisma has not waned.

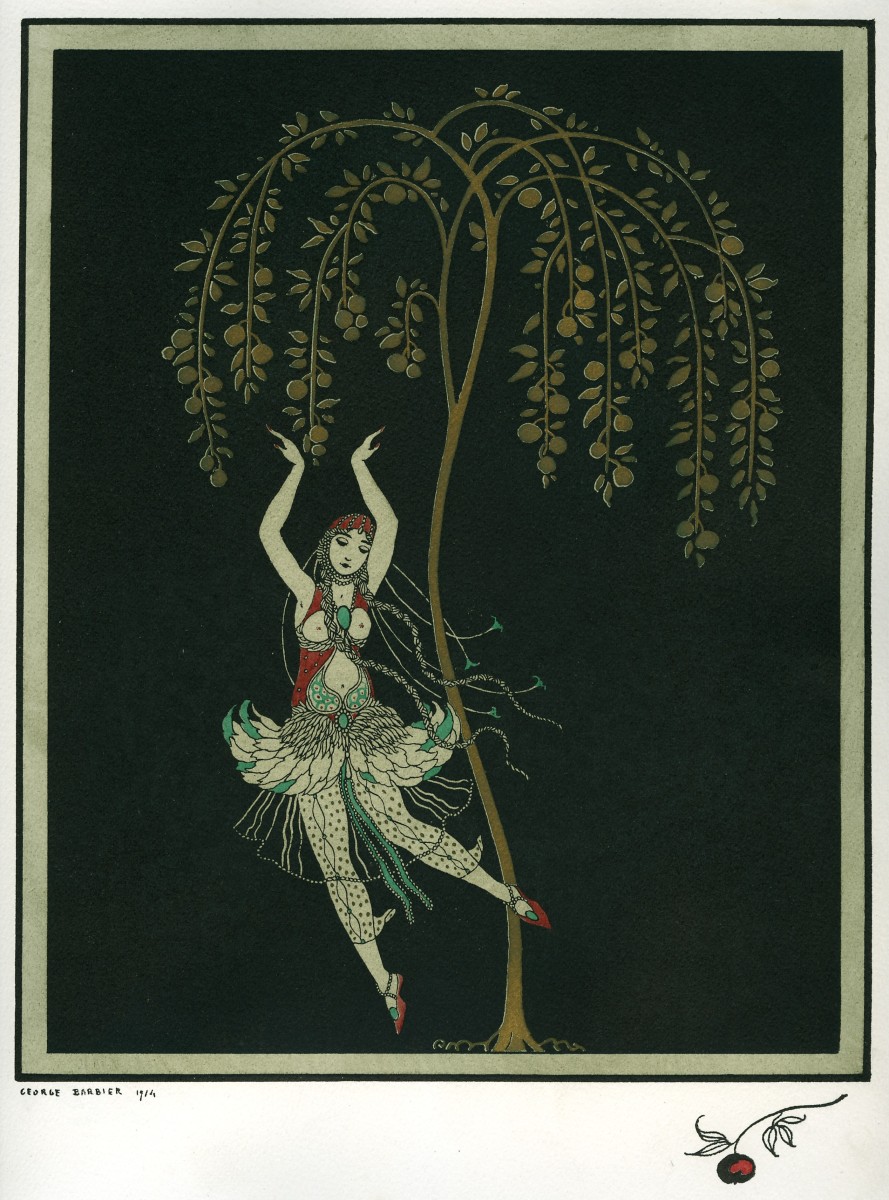

In addition to the essays, the book contains a list of operas and ballets for which Diaghilev was responsible. The list begins in 1908 with Boris Godounov and ends in 1929 with Le Bal. Its strength, or its particular interest, is the way in which the list is illustrated – not with a single image but usually with several from a variety of sources and of different media. So we have Le Coq d’or illustrated with set designs, set models, costumes, costume designs and photographs. The illustrations for Le Spectre de la rose include swatches of fabric, paintings, posters, costume designs, designs for stage props, photographs and sketches. The list is made all the richer as a result of this diverse illustrative material. In fact illustrations throughout the book are themselves a feast of wonders and go well beyond those that have become so familiar in the current literature.

The introductory pages contain a long list of lenders to the exhibition, which will move to Moscow in October 2009. The list of lenders, private as well as institutional, is interesting in its scope as well as for the one or two major collections that are not represented.

A Feast of Wonders is a beautifully and meticulously produced book and a delight both visually and intellectually—much more than an accompanying catalogue.

Michelle Potter, 26 July 2009