Sue Healey has been working on her On View series for several years now. I recall with much pleasure seeing (live—it was pre-Covid!) her very arresting program On View. Live Portraits in 2015, and I also recall, again with pleasure, a number of the portraits of Australian dance ‘icons’ she has made over the years. But Healey has worked on a number of occasions in Japan, Hong Kong and other Asian countries and much her work in the On View series has been collated and edited into an hour-long masterly production called On View: Panoramic Suite, which was recently shown as part of Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art.

This digital presentation began in something of a philosophical way with three performers explaining how they perceived the notion of dance portraiture, which was, at least in part, the focus of the production. ‘The dancer as an expert in being seen,’ said Martin del Amo; ‘How do you see a thought in a gesture?’ asked Nalina Wait; and ‘How are we perceived by others in a changing world?’ mused Shona Erskine.

From there the performance crossed every kind of boundary we might have imagined was possible for a dance on film production. It was panoramic not only in the way the footage was collated from so many different places across three distinct areas—Australia, Hong Kong and Japan—but also because it featured 27 different dancers whose ages ranged from 28 to 106; because the footage was presented from so many different angles, including close-up shots, aerial views and everything in between; and because it was presented with such a variety of screen views including multiple views at any one time.

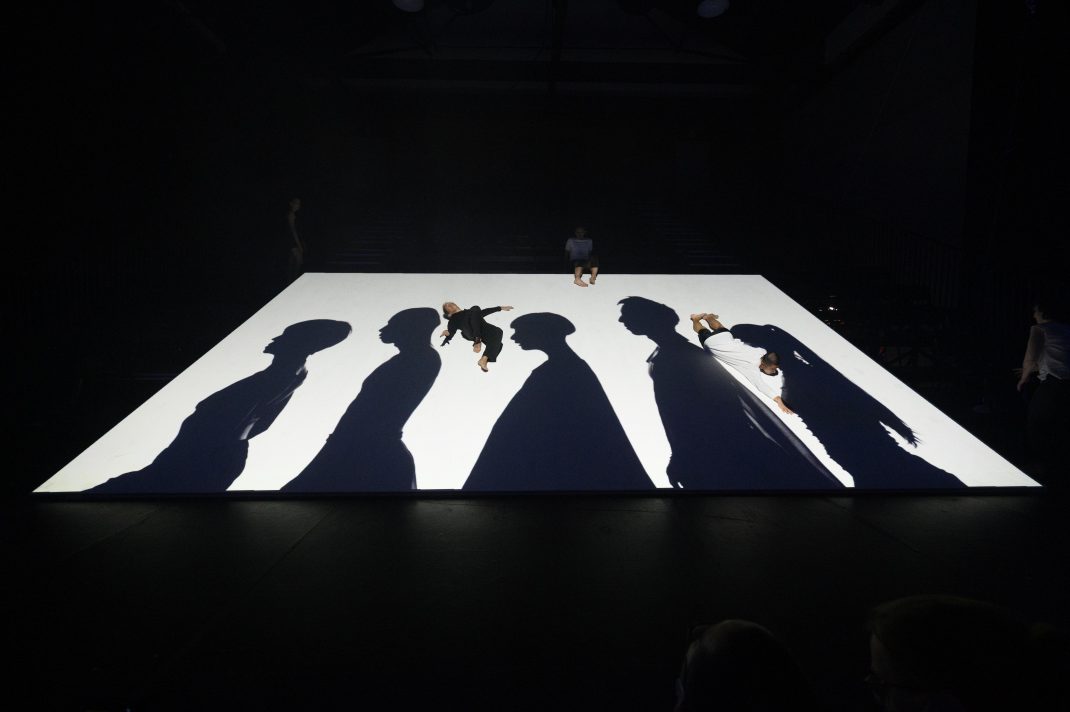

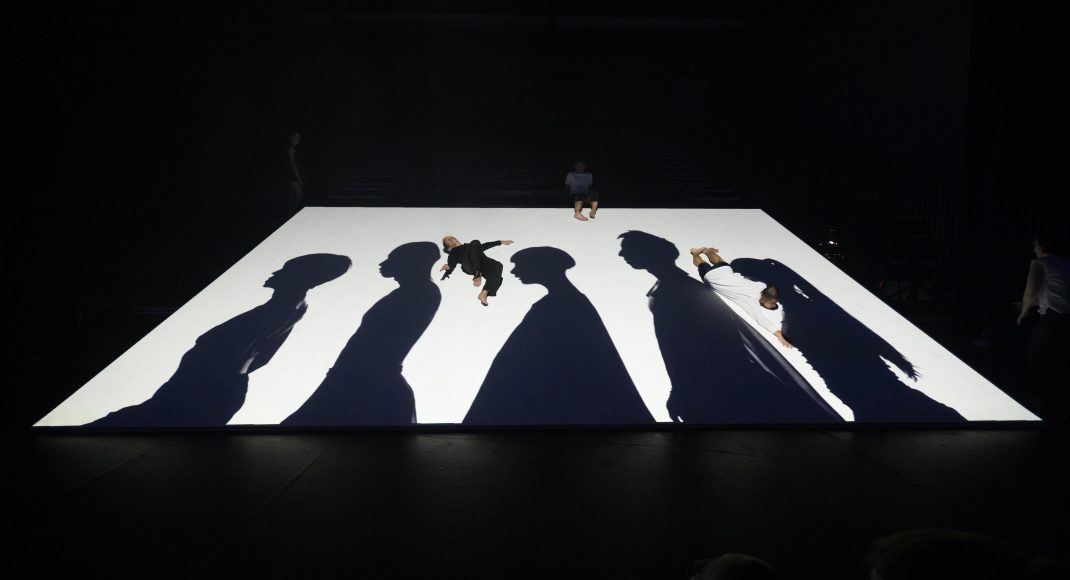

Several sections stood out for me. I found quite fascinating a section that began with percussionist Laurence Pike playing while seated in a square of light. As he played dancers appeared to be falling from a sheet of white material that gradually transformed into a sheet of blue sky. At one stage Pike disappeared from the screen and his place was taken by shadows of performers whose individual shapes kept changing.

A section filmed on Lake George just north of Canberra, which featured dancer James Batchelor, was also particularly eye-catching. We saw Batchelor from an aerial perspective as a solitary figure in a wide, flat, uninhabited landscape, then on multiple screens sometimes with a screen of footage placed next to a screen that was simply a black space. Occasionally, there were close-up shots showing his hands, or his feet engaging with the dirt of the lake floor. It was an interesting reflection and comment on dance and the environment, a concept that was also mentioned by Shona Erskine in the narration at the beginning of the production. This Lake George section also sat in opposition to the section that preceded it when five dancers performed in a tight environment that consisted of nothing more than a small square of light. Not one dancer moved out of the square as they negotiated each other within that confined space.

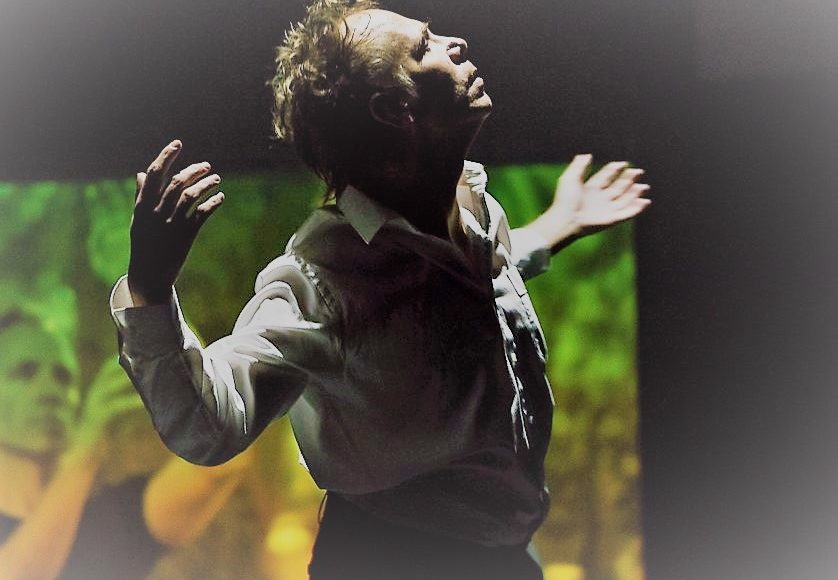

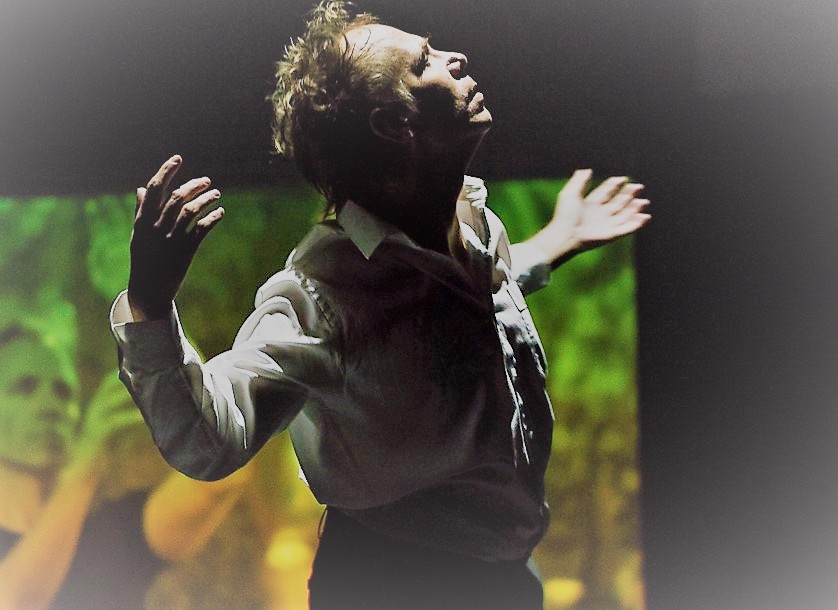

Of the dancers, I found Japanese Butoh artist Nobuyoshi Asai extraordinarily moving. Covered completely in white make-up and wearing only a minimal jock strap-style costume he moved at times as if in a trance, at others like an animal, while at times we saw fury and anger. His performance was intense, potent and physically arresting.

I also enjoyed some moments when Torres Strait Islander dancer, Elma Kris, performed first in a forest of tall, thin tree trunks, and then by the edge of the sea before dancing in the shallows. Again it was partly a reflection of a specific environment.

I have also to acknowledge the entire production/collaborative team for some extraordinary contributions, including Darrin Verhagen for his score and Karen Norris for her lighting. The production was dedicated to the memory of ballerina and esteemed teacher Lucette Aldous who died in June 2021 and who was one of Healey’s Australian dance icons.

Michelle Potter, 30 October 2021

Featured image: Still from On View: Panoramic Suite, 2021. Courtesy of Sue Healey