6 March 2025. Te Auaha, Wellington Fringe Festival

Director, choreographer, performer: Lucy Marinkovich

Composer, pianist: Lucien Johnson

Co-choreographer, performer: Michael Parmenter

Lighting: Martyn Roberts

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The Night has a Thousand Eyes is an hour-long work described as a ‘nocturnal dreamscape of movement and mystery’. The first image is of a vast suspended square tent of white muslin, evoking the cloth draped over a baby’s cradle, lit from within, but empty yet. Piano music is gentle, lullaby-like. Soon the dancer moves in amniotic shadow inside the tent, we glimpse a limb, the edge of her torso, her arm gesturing up, then around, and down, the palms of her hands coming forward into focus. There’s a quiet mood of questioning and waiting as the work awakens to this exploration of space and place, and the piano carries us through.

This is Lucy Marinkovich in the first in a series of vignettes shared with Michael Parmenter, mostly solos, occasionally duets, that play with shadows and silhouettes from the dark and into the light that is sourced from side or back or front, with the two dancers’ bodies, especially arms and hands, striking 1, 000 shapes that hint, suggest, tease, whisper and play in the night.

Impressions are suggested—to wonder at the beauty of an arm outstretched then curved then dissolved—to hold and embrace an infant, perhaps—keeping silent reverie alone beneath a dark sky that shimmers with 1,000 stars, in no specific place but here. Nights are long but the piano, in Lucien Johnson’s driving score, carries us through.

Parmenter dances alternate sections, he too is a silhouette, then moving and flowing, then held in chiselled positions. He will later be the insomniac out in the night streets of Paris, marking out fragments of old tap dance routines, or flashing a thousand tiny lights onto a dark wall, imagining he’s alone but we are watching. These are film-like dream-like sequences, and still the piano carries us through.

The performers are not connected as characters, nor is any specific thematic narrative developed. They move in alternate sequences that build a sympathy and empathy between them as they share the thoughts and things that arrive in the nights—both theirs and ours. A scene comes to seem like a poem, each separate yet belonging together in a selected collection.

The hub of the work is the mesmerising Serpentine Dance reconstructed by Marinkovich after Loie Fuller moving in the earliest stagings of electric light on stage over 100 years ago. Vast swathes of white silk are held aloft with poles to extend the wings into a celestial realm. The carefully chosen moves and curves and swoops bring the silk into its own life, making invisible air now visible, eventually enveloping the dancer, and still the piano carries us through.

So the two dancers, but also the lighting design that in turn brings textiles to life, effectively make a cast of four performers. We cannot take our eyes off any of them.

My wish, although maybe not practical, would have been to see the pianist in low light side-stage, visually holding these vignettes together as indeed the music did throughout.

Jennifer Shennan, 7 March 2025

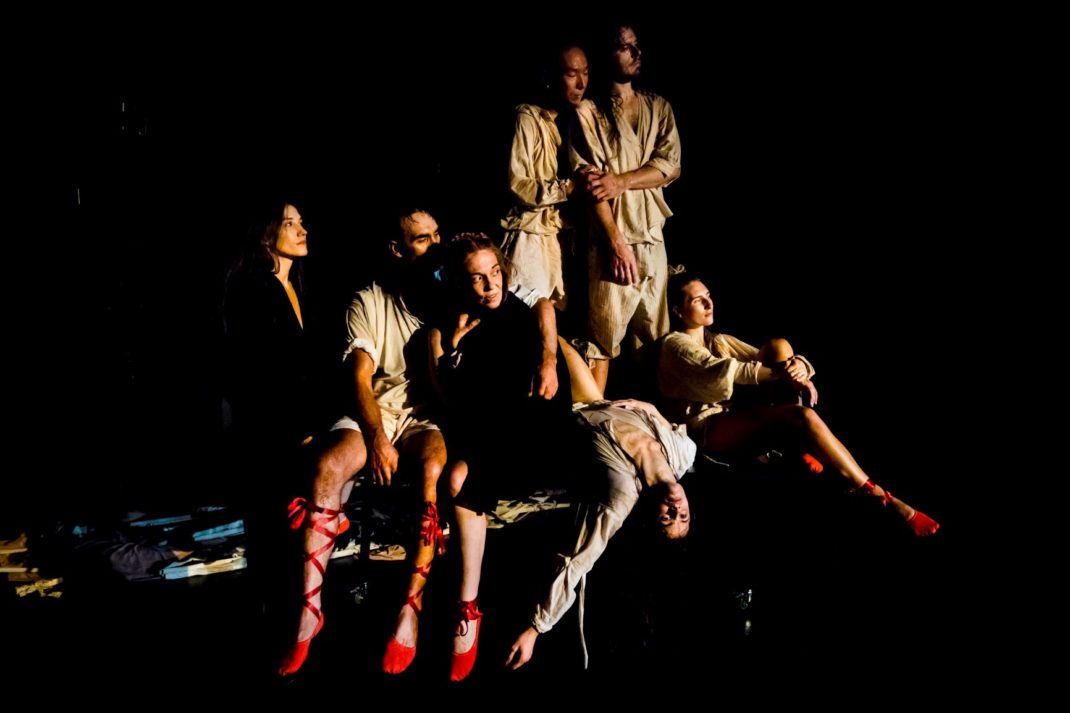

Featured image: Lucy Marinkovich in a reference to Loie Fuller’s Serpentine Dance. The Night has a Thousand Eyes, Borderline Arts Ensemble, 2025. Photo: © Lucien Johnson