12 & 13 March 2020. Circa Theatre, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

Choreographer/dancer Lucy Marinkovich and composer/saxophonist Lucien Johnson combined to produce Strasbourg 1518, a fusion of dance, music and story into theatre. Their take on that specific historic outbreak of dancing mania is given psychological and political context using tropes of religion, rationality, visual art and literature. The work does not stay quaintly back in earlier centuries however, but alludes to 20th and 21st century dance marathons, protests and populist movements, epidemics and pandemics. Art as protest, as revolution, is their call.

Whoa! Isn’t that a heady mix with too much libretto already? (We’ve all seen from time to time a choreography top-heavy with content, though in my experience we are far more often shown dance that has no tangible content whatsoever … as in program notes that claim, for example ‘My choreography is about the turbulent uncertainties of the human experience’ or ‘I’m a female choreographer and this prop is a metaphor of my gendered existence but audiences are welcome to interpret it in any way they like’ or ‘Look at what I can do with my body if I just keep trying harder to point my foot like a raven’s claw’ etc. etc. etc.). Strasbourg 1518 is a danse macabre that remains accessible through a string of riveting scenarios of times and places beyond the reference of its title. It’s as chilling and wild, and as beautiful, as you want dance in the theatre to be.

A show like this will have taken between two and five years to prepare, shape and produce. It is about choreomania, a series of dance epidemics in Europe recurring through different periods of 14th through 16th centuries, as well as closer to our time. Some of the best dance literature is written around the topic of dance and emotion co-existing—by Backman, Meerloo, Bourguignon, de Zoete, Lange, Schiefflin—but this work does not simply reproduce known material. As we arrive at the theatre, couples are already quietly mooning in close dancing, slow motion, in the foyer. In the auditorium we find the stage filled with more couples, in a nod to the exhausting dance marathons of 1920s and 30s. A special couple emerges from among—Michael Parmenter and Lucy Marinkovich, a.k.a. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, a.k.a. Death and the Maiden.

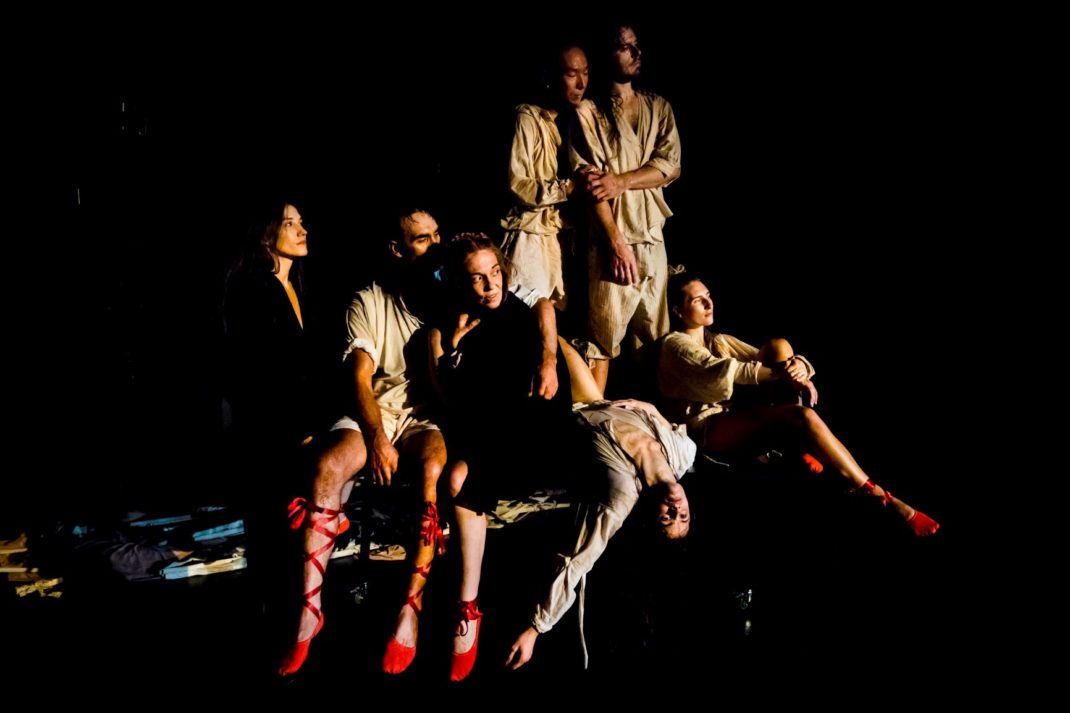

Johnson is a central presence onstage throughout, playing saxophone brilliantly (so what if the instrument was invented in mid-19th century?) and driving all the music that shapes the show. Marinkovich is luminous as The Maiden, veteran dancer Parmenter plays Death with an assuring calm and alluring equanimity. There’s a cast of six wild Choreomaniacs (Jana Castillo, Sean MacDonald, Xin Ji, Katie Rudd, Emanuelle Reynaud and Hannah Tasker-Poland) who dance their pants off, more or less literally, and their relentless moving demands a stamina that itself verges on the insane. France Hervé is stunning as The Rational Man narrating the commentary, but by the end has mystically transformed into a kind and loving Woman.

All the performers are stellar and deliver way beyond the call of duty, though the character edge is held by Castillo as Frau Troffea who led the mania, by MacDonald as The Bishop, and by Tasker-Poland as a reluctant lunatic. Politicians cried out ‘Stop dancing, it is forbidden’, Rich Men cried out ‘Keep dancing so we can tax you and fine you’, Doctors cried out ‘Only increased physical activity will cure this illness of the boiling blood, so dance more and dance faster’. Small wonder people went mad.

Slogans on banners shout out the pain and confusion of those who protest, who suffer, who do not understand, or who understand all too well—’Feral pigs steal food’; ‘Collection of firewood is illegal’; ‘We deeply distrust landlords’; ‘All my friends are sick. Is it infectious?’; ‘We all have syphilis’; ‘We are burdened with taxes’; “Je danse donc je suis’.

We feel a frisson of recognition whenever images of European paintings are evoked—Breugel and Bosch are there, the blind leading the blind, Dürer and Rembrandt are there, the body beautiful and the body ill. Are we in El Prado? or a novel by Saramago? A shaft of respite eventually enters when Death and the Maiden bring a trolley of gifts to ease the pain and despair—a pair of red shoes for each dancer. O dear, we know the dancing will not stop after this chord, this cord, connects a motif from old folktale to modern film…condemned to dance until dead.

But it’s become a different dancing now—not old so much as timeless. Now come movements borrowed from the linked lines of farandole archways, the beat of estampie, a swaying branle, a folding reprise and conversion from basse danse, a cheerful path of tordion, an uplifting saltarello. These are dances for life not for death, for a community of friends on Earth, not for those out of control on a slippery path to a fake Heaven or a real Hell.

No-one in the team could have anticipated how the premiere season here would play out. Lucky me, I saw the first two performances but also planned to see the remaining two since there’s a lot in such a show to think and write about. Unfortunately the third and fourth performances were cancelled minutes before curtain-up, and confusion around how that was communicated by management could have come straight from the choreographic libretto itself. Eventually it transpired it was a covid-19 health-related issue though no one in authority would say so when it mattered, as the audience continued to assemble in the foyer. That weekend was also the first anniversary of the brutal mass attack on Christchurch mosques, 15 March 2019, so although citizens went about their weekend calmly here, there was always an eye being kept on the rear-vision mirror wherever you were.

Lucy, devastated by the course of events that sabotaged their season, begged me to write about the work and not the cancellations. Sorry Lucy, they belong together, and your show is the stronger for that. Life will move on, some things will change but some will not. I imagine you and Lucien will use your filming of the work to create a prelude to the prologue and a postlude to the epilogue. There will be a return season, and your work will come to earn the recognition it deserves. It evokes for me Martha Clarke’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, and that’s high praise.

Jennifer Shennan, 17 March 2020

Featured image: Lucien Johnson as The Musician with Katie Rudd as a Choreomaniac in Strasbourg 1518. Borderline Arts Ensemble, 2020. Photo: © Philip Merry