22 January 2017 (matinee), Carriageworks, Eveleigh (Sydney). Sydney Festival 2017

The walk down the corridor to enter Bay 17 of Carriageworks for Champions was accompanied by the recorded sound of crowds cheering and referees’ whistles blowing. We entered the space through an arch of balloons and before us, on a green grass-like floorcloth, was a dancing mascot. The scene was set for Martin del Amo’s Champions, a dance work commissioned by FORM Dance Projects and presented as a sporting event, a football match to be more precise. Del Amo’s program notes stated, ‘It is a commonly held belief that sport and the arts do not go together.’ Champions was del Amo’s comment on that pervasive attitude. It also had political overtones about women in sport, especially in those sports that are more often than not regarded as ‘men’s work’.

The first thing to say is that the mascot—a swan dressed in a tutu—was an entrancing part of the show. Inside the costume, Julie-Anne Long kept us entertained before the show proper began and then mid-piece in the half-time section. She crossed her wrists demurely in front of her à la Swan Lake, executed little piqué style steps, and waved her arms up and down like a dying swan. Smart choreography from del Amo and amusing execution by Long, despite the difficulties her orange webbed feet must have caused her.

The rest of the dancers/football players, all women, included some of the best contemporary dancers working around Sydney today. One by one, as they warmed up for the dance/match, they were introduced by a commentator (real-life sporting commentator Mel McLaughlin), who appeared on video on a series of upstage screens. Then the main section of the work began with a series of group exercises and, a little later, with comments, again via the video screens, about salaries for men and women in sport, in particular salaries received by the Australian men’s soccer team in comparison with the women’s.

In preparation for Champions, the dancers had worked with the Sydney-based soccer team, the Western Sydney Wanderers, so there was a certain authenticity to their sporting moves. But from a dance perspective, the most interesting section came when the dancers lined up downstage and began to wave gold pom-poms, as we are used to seeing from cheer squads. Throwing away the pom-poms (thankfully) they began to take a series of poses that seemed to teeter between football moves and contemporary dance poses. At first the moves seemed unconnected but slowly it became clear that in fact there was a set number of moves and the dancers had an individual sequence they were required to follow. At the end of this section the entire row began working as one with every dancer taking on the same pose. I enjoyed the choreographic surprises that characterised this section.

Again interesting from a dance perspective were those moments towards the end of the piece, when individual dancers were lifted high above the heads of the group. Celebratory moments perhaps?

Champions was a clever work. It was fun to laugh at the swan mascot and the references being made to certain works from the ballet repertoire. It was interesting, too, to reflect on the sporting commentary and interviews recorded with the dancers and screened for viewing by the audience. Those comments and replies often reflected common thoughts about contemporary dance. A question from the commentator, for example, about what was happening onstage had the reply, ‘A lot of people are baffled by contemporary dance.’

My regret is that the work really didn’t give us much of a chance to see the exceptional abilities of people like Kristina Chan, Miranda Wheen, the Pomare sisters, in fact all eleven women. Champions was enjoyable but, despite its apparent intentions to make a social and political comment, to me it was a slight work.

Michelle Potter, 25 January 2017

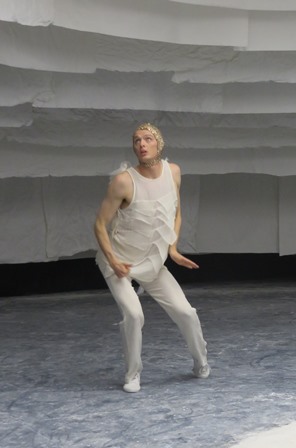

Featured image: Kristina Chan in Champions, 2017. Photo: © Heidrun Lohr