20 April 2019. Teatro alla Scala, Milan

Sitting in the so-called ‘first balcony’ of Teatro alla Scala in Milan gave me a view of Wayne McGregor’s Woolf Works that I have never had before. In I now, I then, the first act based on Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, I saw more clearly the structural elements of the set, the darkness behind those structures, and the way the elements of the set impacted on the storyline. In the second act, Becomings, based on Orlando, I had a view of Lucy Carter’s spectacular lighting design that was quite different from what I saw in earlier performances. In act three, Tuesday, based on The Waves, I was able to see McGregor’s choreographic patterns more clearly than before.

Of course I missed what I had seen on previous occasions, especially some of the finely detailed moments of choreography, and some details of personal connections between the dancers. But, like much in Milan, tickets to the ballet are expensive and, in any case, as I looked down from my central position so close to the ceiling (the ‘first balcony’ is the fifth of six semi-circular galleries that are part of the theatre), I wondered how well one could see from the orchestra stalls anyway. Down there the floor of the auditorium seemed very flat, although no doubt the stage was raked.

This post discusses the impact the new, on-high perspective had on my thoughts about Woolf Works. My previous reviews of Woolf Works are at the following links: London 2017, Brisbane 2017.

Inside the Teatro all Scala

For me, I now, I then has always had the strongest narrative element of the three acts. It follows various threads of Clarissa Dalloway’s life and loves, but does so through Clarissa’s memories. Having the view from the ‘first balcony’ of the three large wooden structures (they are like enormous picture frames) that make up the set in this act, seeing them move position, come together and separate repeatedly, gave extra strength to the notion that the story was moving through Clarissa’s life. Those who touched her life disappeared behind the frames occasionally only to reappear later, and the frames themselves seemed larger than I had previously noticed—life itself exists on a grand scale—and the figures smaller—we are are born to die while life, a greater force, continues.

I have always loved the final moments of act one where the five people who have especially touched Clarissa’s life dance together, change partners, come back to each other, then one by one disappear into the void of the darkened stage leaving Clarissa alone to contemplate her memories. The whole notion of the changing relationships that mark our lives was made clearer to me as I looked down on the action and on the visual elements that marked out the stage space.

The cast was led by Alessandra Ferri as Clarissa; Federico Bonelli as Peter, Clarissa’s early love interest; Catherina Bianchi as the young Clarissa; Agnese di Clementi as Jenny, Clarissa’s female friend; and Mick Zeni as Richard, Clarissa’s husband.

Federico Bonelli, Caterina Bianchi, Alessandra Ferri, Mick Zeni, and Agnese Di Clemente in Woolf Works Act I, 2019. Photo: © Marco Brescia and Rudy Amisano, Teatro alla Scala. This moment occurs towards the end of act one as Clariss (Alessandra Ferri) interacts with those who have shared her life.

A major characteristic of act two, Becomings, has always been Lucy Carter’s astonishing lighting design. Earlier I wrote that it ‘sometimes divides the stage space, other times it beams out into the space of the auditorium. It colours the space, and darkens it too, and laser beams occasionally shoot across the stage’. This time it seemed quite clear that many of the lighting effects indicated the multiple decades/years that are covered in Orlando. Throughout this act the dancers moved through some very clear geometrical patches of light as well as some cloudy, misty patches. And again the dancers seemed small, this time in relation to those clouds and shapes of light. Then as the act closes beams of light are projected into the auditorium. From a height they no longer blind the eyes but suggest clearly that we were now part of the ‘becoming’. Time has passed and reached ‘now’.

Nicoletta Manni and Timofej Andrijashenko in ‘Becomings’ from Woolf Works. 2019. Photo: © Marco Brescia and Rudy Amisano, Teatro alla Scala

Act 3, Tuesday, begins with a voice-over reading Virginia Woolf’s suicide note to her husband before she drowns herself in the River Ouse, her pockets filled with stones. The letter is dated Tuesday.

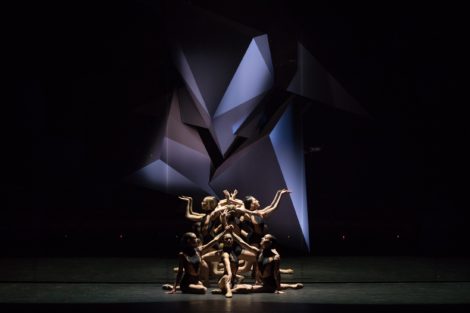

I have to admit that previously the choreography in this act seemed to me to be a little messy, apart from the very moving pas de deux that follows immediately after the voice-over. But, looking down on the movement patterns McGregor had created on the dancers, his intention with the choreography seemed clearer. I saw the many different variations that one might encounter in water—swirls, rips, eddies, gentle waves, tumultuous breakers, everything was there. There was no mess, just a myriad of watery patterns danced nicely by the corps de ballet of Teatro alla Scala with the participation of students from La Scala Academy.

*********************************************

Not being familiar with the dancers of La Scala it is hard to make comments about specific dancers. But I recall Nicoletta Manni from her performances in Australia in 2018 and I enjoyed her dancing in act two. I was also impressed by Timofej Andrijashenko both in act one as Septimus, the World War I veteran who commits suicide, and in act 2 for some spectacular dancing. Ferri and Bonelli I have seen before in their roles as Clarissa and Peter and once again they gave exceptional performances.

In all, I loved seeing Woolf Works from a completely different position in the auditorium. It simply confirmed my opinion that Woolf Works is a ballet that I will never tire of seeing.

Michelle Potter, 23 April 2019

Featured image: Alessandra Ferri and Federico Bonelli in Tuesday from Woolf Works, 2019. Photo: © Marco Brescia and Rudy Amisano, Teatro alla Scala. This image is from the very moving pas de deux that opens the dancing in Tuesday