14 November 2016, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London

This triple bill of works by Wayne McGregor, including Multiverse his newest commission, was presented in celebration of McGregor’s ten years as resident choreographer with the Royal Ballet. While all three works clearly had the ‘McGregor touch’ in terms of a choreographic interest in the extent to which the body can be pushed to extreme limits, each was also quite distinctive in its own right.

Chroma, the oldest of the three, was first made in 2006. It was the work that inspired Monica Mason, director of the Royal Ballet at the time, to offer McGregor the position of resident choreographer. Ten years on Chroma retains its minimalist beauty in its design with a set by John Pawson, costumes by Moritz Junge, lighting by Lucy Carter, and a score by Joby Talbot and Jack White III. It is still thrilling to watch choreographically with its extended limbs and emphasis on a fluid torso. But what made a difference in the current production was the presence in the cast of five dancers guesting from Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater: Jeroboam Bozeman, Jacqueline Green, Yannick Lebrun, Rachael McLaren and Jamal Roberts.

It is tempting to say that these dancers brought a different aesthetic to the choreography, and perhaps they did. Certainly I sensed that they injected a more powerful human quality, something emotional into the steps. It is hard to articulate just why the way they danced was different but it seemed like they had a different kind of focus in their movement. A greater sense of physicality and a different muscularity maybe? Whatever it was, it added a different level of interest, which is not to denigrate in any way the five fabulous Royal Ballet dancers who completed the cast: Federico Bonelli, Lauren Cuthbertson, Sarah Lamb, Steven McRae, and Calvin Richardson. The 2016 production indicates that Chroma lives on and has the power to grow. (Thoughts on my first viewing of the Royal Ballet in Chroma in 2010 are at this link.)

The closing item was Carbon Life, made in 2012. Again it had lighting by Lucy Carter, sometimes as in the opening moments eerily green, other times full on bright white. Design was by English fashion designer Gareth Pugh and music by pop/funk artists Mark Ronson and Andrew Wyatt.

I especially enjoyed some of the earlier sections where unisex seemed to be the order of the day. Men and women wore similar costumes: short black trunks and, for the women, a skin-coloured midriff top that tightly enclosed the upper body and made them appear topless. Added to this costume both sexes had slicked-back hair (wigs?) that added to the similarity in the look of the sexes. Choreographically this section seemed at times like a ballet class engaged in a kind of temps lié exercise.

A later section was distinguished by some incredible costuming consisting of black, stiffened additions to the head, legs and other parts of the body. They were a little like a cross between KKK headgear and Cambodian dance costume attachments, or perhaps a bit like Ballet mécanique. Certainly the shapes were architectural and the body began to sprout structural additions. The singular attraction of Carbon Life, however, was the presence of live musicians onstage/upstage usually partially hidden by lighting or a screen of some sort. Their playing was loud and engaging and, when they appeared to take a curtain call, they too were dressed to kill. But in the end the choreography seemed like a minor player in all this and Carbon Life took on the guise of a fast-paced video clip rather than an exercise in choreography.

In between Chroma and Carbon Life came the newly commissioned Multiverse, which, incidentally, the Australian Ballet adds to its repertoire in February 2017. I thought it was the least interesting of the three works, although program notes were full of explanations and thoughts about McGregor’s intentions, which centred on the current refugee crisis and other such global perils. Musically (or sound-wise) it was diverse and consisted of two pieces by Steve Reich—a specially commissioned work Runner, and a 1965 piece It’s gonna rain, of which the second part is the voice of a Pentecostal preacher holding forth in Union Square in San Francisco on the biblical story of Noah and the flood. Perhaps because I found William Forsythe’s work, Quintett, so moving—it used Gavin Bryars recording of a homeless man singing over and over Jesus’ blood never failed me yet, which sat emotively beside the choreography—I found the use of the preacher’s words unaffecting. Unlike the Forsythe piece, in Multiverse choreography and recording didn’t seem to reflect each other in a thought-provoking manner. After all this, the second Reich piece, Runner, was simply soporific for me.

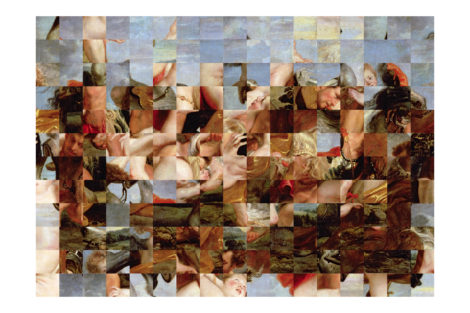

Nevertheless, Multiverse began strongly with a male duet—I saw Luca Acri and Marcelino Sambé—full of tension and drama. It was by far the most interesting part of the work choreographically. The section that followed referenced the plight of refugees. This idea came across most strongly via the set by Rashid Rana in which fragmented images appeared. Some were contemporary shots, others were from the well-known painting by Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa. But there were rather too many moments when the dancers simply stood still and, while this might be seen as giving way to the power of the images and what they represented, it was hardly compelling from a movement point of view.

Perhaps Multiverse needs more than one viewing in order to appreciate its complexities? But then not everyone has such a luxury. The idea of making dance that reflects current society is indeed admirable (and I am a fan of McGregor’s Live fire exercise). But on this occasion it simply didn’t work for me and I began to wonder whether I should not have read the detailed program notes because what was written and what appeared onstage didn’t really match.

Audience reaction was a curious thing too. As the curtain went down, behind me an enthusiastic audience member was cheering long and loudly. Beside me another was boo-ing!

Michelle Potter, 19 November 2016

Featured image: Wayne McGregor. Photo: © Nick Mead