10 April 2017, Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

The Australian Ballet’s latest program of three contemporary ballets is, artistically speaking, a very mixed bill. It certainly shows off the physical skills of company dancers, but choreographically it has its highs and lows.

The program opened with Faster, a work by British choreographer David Bintley, which he made initially for the London 2012 Olympic Games. It may have been an interesting work for that occasion, but I just can’t understand why it was thought worthy of reviving for repertoire. Although dancers have physical skills that are certainly athletic, in my book dancers are artists not athletes. There was nothing in the Bintley work that allowed the dancers to show their artistry. They seemed to run around the stage a lot, occasionally with a jump here, or a twist there. They pretended they were fencing, shooting a ball through a hoop, engaging in high jumps and other aerial sports, and so on. Sometimes they feigned injury, or despair, or something. But really I would rather watch professional athletes engaging in sporting activities rather than dancers pretending. Faster was a very lightweight work and not my idea of what I want to see from the Australian Ballet (or any ballet company for that matter).

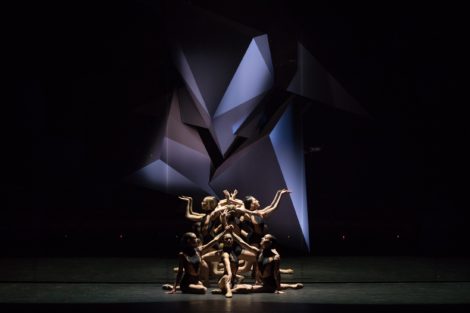

The highlight of the evening was Tim Harbour’s fabulous new work, Squander and Glory. Choreographically it explores not so much how the body moves through space—although that happens—but how the body can fill the space around it. Sometimes there were some quite beautiful classical lines to observe, along with large groups of bodies gathered close together and moving across the stage. But at other times that classical look and ordered arrangement collapsed and we could see something more akin to a heap of bodies making shapes, lines and swirls of infinite and fascinating variety. (And I’m using ‘heap’ here in a positive sense rather than suggesting it was a mess).

But not only was Squander and Glory thrilling, and surprising, to watch from a choreographic point of view, it was also a wonderful example a how the collaborative elements can add so much to the overall feel and look of a work. I have long admired Benjamin Cisterne’s powerful and courageous vision for what lighting can contribute to a work, and that vision was absolutely evident in Squander and Glory. His use of a mirrored cloth in the work doubled our view of the number of dancers appearing on stage, and allowed us to see the choreography from two different angles. It brought an extra layer of excitement to the work, and I was amazed and delighted that those mirror images didn’t detract from the work, as so often happens when film clips or projections of some kind are introduced into a dance piece.

Then there was Kelvin Ho’s towering structure in the background, which reminded me of part of a Frank Gehry building, or a cone-like sculpture similar to those made by Australian sculptor Bert Flugelman. But it also had a kind of mystery associated with it. Logically it had to be a projection but its presence was so powerful, without dominating the choreography or Cisterne’s design, that I had to wonder where it was physically located. It was a brilliant addition to a seamlessly beautiful collaboration, which to my mind was enhanced by the relentless sound of Michael Gordon’s score, Weather One.

The program closed with Wayne McGregor’s 2008 work, Infra. I am a McGregor fan for sure, but I found Infra underwhelming after Squander and Glory. The work emerged from McGregor’s thoughts about human intimacy and its varied manifestations. But the expression of these ideas seemed dry and even sterile after the lusciousness and heart-stopping excitement of Squander and Glory. Set design by Julian Opie was a parade of faceless people, drawn as black outlines, hurrying across an LED screen above the stage. But it simply added to that feeling of sterility. Even Lucy Carter’s lighting, which has in the past been absolutely amazing (most recently in Woolf Works), didn’t excite.

Bouquets to the team who created Squander and Glory. It was a truly remarkable new work and certainly made my night at the ballet worthwhile. I look forward to a second viewing.

Michelle Potter, 14 April 2017

Featured image: Brett Chynoweth, Vivienne Wong and Kevin Jackson in Squander and Glory. The Australian Ballet, 2017. Photo: © Daniel Boud