Via the ROH streaming platform

Frederick Ashton choreographed his ballet, Enigma Variations, to the similarly named score by Edward Elgar: Royal Ballet publicity describes the ballet as an ‘ode to the composer Edward Elgar’. The ballet depicts several of Elgar’s friends and family who are seen at Elgar’s home as he ponders the outcome of a request to conductor Hans Richter regarding input into the premiere performance of the Enigma score. Richter eventually sends a telegram to Elgar agreeing to the request to conduct, and Elgar and his friends gather as one to share Elgar’s pleasure (and relief?).

I had never previously seen the ballet, which received its premiere from the Royal Ballet in 1968, and I came to the streaming with pretty much no knowledge of what was happening, not even why the mysterious envelope that arrived at the end of the work caused the thrill that it did for the cast. But even without this knowledge it was a fascinating work choreographically and for the way the collection of people who danced the various and diverse roles were so strong in their characterisations. It is also exceptionally designed as a period piece by Julia Trevalyan Oman. After watching it this first time, my curiosity sent me on a research trip via the internet and via David Vaughan’s engrossing book Frederick Ashton and his Ballets. I watched the stream again.

Christopher Saunders performed the role of Elgar and did so with a strength that drew attention instantly and constantly. The opening moments in which Elgar’s wife, danced by Laura Morera, offered her support for her husband as he struggled to remain unworried by his situation set the scene beautifully. It looked calm and simple in many respects but it was choreographically quite complex especially in relation to the various lifts included.

Francesca Hayward gave a memorable performance as Dorabella, a young friend of Elgar. Dorabella suffers from a speech impediment and this aspect of her persona was recognised with fast moving and constantly changing choreography—including fast runs and little hops on pointe. But, in addition to this somewhat remarkable choreographic inclusion, Hayward projected a winning, unforgettable youthfulness.

Another standout character was Arthur Troyte Griffith, an architect and a close male friend of Elgar, danced dramatically and exuberantly by Matthew Ball. But the entire cast performed with such skill and dramatic input that it is hard to single out individual performances. One aspect of the choreography that stood out for me was Ashton’s skill in creating movement that never looked as though it was specific to particular parts of the body. Movement just coursed through the entire body.

The ballet is episodic in structure and crosses time. But it is just beautifully structured and performed and will stay in my mind for a long time to come.

Michelle Potter, 20 February 2025

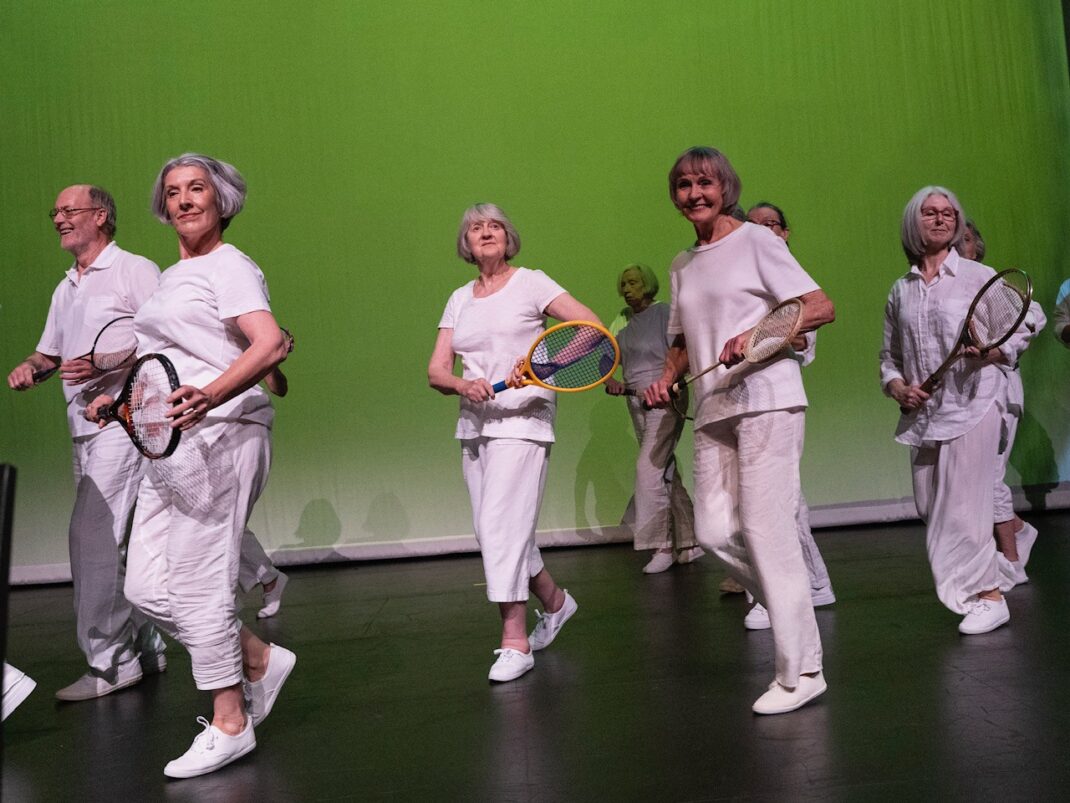

Featured image: Artists of the Royal Ballet in the closing moments of Enigma Variations. The Royal Ballet. Photo: © ROH/Tristram Kenton