While preparing for my recent Spotlight talk at the Arts Centre Melbourne I had occasion to listen to an oral history interview I recorded for the National Library in 2002 with Bill Akers. One of the many positions Akers held across the course of his very full life was director of productions with the Australian Ballet. He was also an inspired lighting designer, worked in various roles with the Borovansky Ballet and, prior to that, worked in theatre and film and on radio as an actor.

Ultimately, I used an audio clip from the interview in the talk and an audience member commented at the end on how nice it was to hear Bill’s voice again. Well that’s one of the benefits of recording oral history. But apart from anything else he had a beautiful voice. It was deep, generous and cultivated. In his interview he had something to say about that voice, which relates to his first radio appearances:

I became a club leader and gymnasium instructor in the YMCA and one Friday night, having lost the National Table Tennis Championship, I was standing rather dejectedly in the boys’ division and the telephone rang. A man called Bill Arthur, who subsequently became a parliamentarian and went on to join the House of Reprehensibles [sic]—he ran a show called ‘Over to you’, said ‘Look Bill, an actor hasn’t turned up for an interview, would you do it?’

Well, with characteristic reluctance I rushed out of the YMCA, ran down Pitt Street at the rate of knots, rushed round into Market Street and was up in Studio 149 before you could breathe. I hadn’t the faintest idea what I was doing. They shoved a script into my hand and said: ‘Say anything after the letter A’. So I did the interview and I was ‘A’. I didn’t know who ‘A’ was but they would go out and interview a boy who was perhaps an apprentice plumber or an apprentice clerk or something or other and they would get the details of his job and what the prospects were and things like that. And an actor would come in and play that boy on the radio.

Well the following Tuesday they rang me up and said would I do it for a year, so I got a contract. At the end of the year, of course I wanted to go into the theatre and I wrote to Keith Wood who was the director of that program and told him this. And he rang me up and very kindly said to me: ‘Look, Bill, you’re very talented but if you’re going to become an actor, the first thing you have to do is do something about that terrible voice’. Well I did have a voice that was very high at the time and very nasal. So high that only dogs could hear it. It was very nasal and Australian and so on. So he sent me to Bryson Taylor who was a voice production teacher who listened to me for five minutes and said: ‘Have a cup of tea’. And he talked to me for a while and at the end he said: ‘Look, I’m sure you’re very talented but I don’t think anybody could ever do anything with that voice’. I’ve never drunk tea since.

Not long after this Akers became a student at the Rathbone Academy of Dramatic Art in Sydney and went on to appear on radio in episodes of the Lux Radio Theatre and the Caltex Theatre. He also worked with the John Alden Company playing Shakespearian roles, and with the J. C. Williamson organisation in a variety of productions.

At the request of Harald Bowden of the J. C. Williamson organisation, Akers joined the Borovansky Ballet as assistant stage manager in the 1950s. His interview contains recollections of arriving at the theatre for the first time as ASM, his impressions of Borovansky and his thoughts on the Borovansky Ballet.

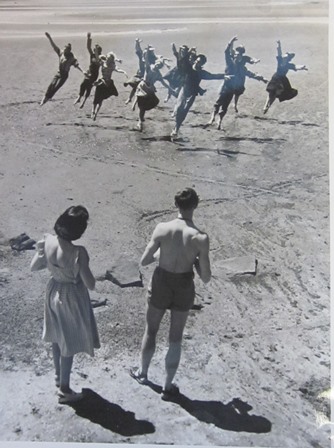

I walked through the stage door of Her Majesty’s Theatre at about 11:30 in the morning to be confronted by these fifty raging egos jumping up and down and whirling around in the air. They were rehearsing a ballet called Symphonie fantastique and Mr Borovansky was standing on a chair shouting imprecations at these people. He had a pair of baggy old corduroy slacks on … He had a Chesty Bond’s singlet, rather loosely flapping and ballet slippers and a beret on the back of his head, which fell off as he got down onto the stage.

To me, despite the fact that I think I’ve met lots and lots of very great people in my life—I’ve been very privileged for that—he is the greatest person I think I’ve ever known. I think he contributed more to Australian theatre, particularly to dance, than anybody else. He created a ballet audience. He made ballet in Australia … he was just a fantastic man [with] particular drive and charisma. When you worked with Mr Borovansky you were alive twenty-four hours a day. He was the most stimulating person imaginable.

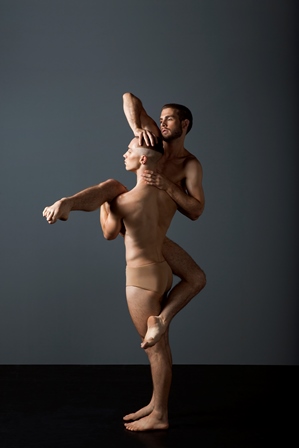

The Borovansky Ballet was a great big, magnificent, glamorous rough diamond with wonderful ballerinas. Boro virtually created ballet in this country, which is supposed to be a sports minded country, a situation that led at one stage to us having the greatest per capita ballet audience in the world. And that went on for twenty years … In Boro’s day, of course, triple bills were tremendously popular but he knew how to plan them. He was a genius at planning triple bills. He would introduce a new work like Paul Grinwis’ ballet Eternal Lovers. He would sandwich it in between the second act of Swan Lake and Le Beau Danube, which he knew the public adored. His triple bills were wonderful.

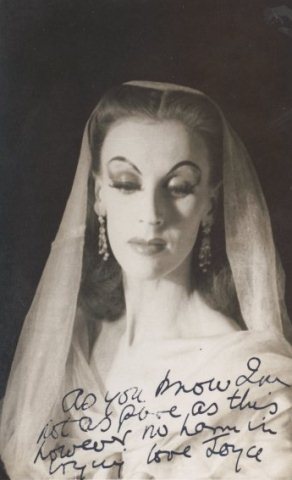

Throughout the interview Akers tells many other anecdotes about people he met and people he admired. He has the following to say about Joyce Graeme when she toured in Australia with Ballet Rambert, 1947‒1949:

I’ve seen some magnificent Queens of the Wilis [in Giselle] but there will never be another Queen of the Wilis like Joyce Graeme. She was an icicle. It was just a magical performance. She wasn’t nearly as good a dancer technically as many of the others I’ve seen but the icy chill she brought to the stage … and of course she was very tall and very thin and she was an electric presence on stage.

And he recalls the arrival of John Cranko to stage Pineapple Poll for the Borovansky Ballet in 1954:

[Cranko] first came to Australia for Mr Borovansky to stage Pineapple Poll. Wonderful fellow he was. Great sense of humour. And he’d seen Symphonie fantastique the night before. We were all waiting on stage, breathless, for this great, new, young choreographer to arrive. And at five to ten I used to set off the alarm and class used to start promptly at ten … Well Mr Cranko wasn’t there and everybody was standing on stage thinking: ‘He would never dare to be late’. Then the two doors at the back of the theatre flew open and he came screaming across the stage doing grands jetés, which is what started the final movement of Symphonie fantastique. And he got to the centre of the stage and he said ‘Well there you are, I have proved to you that I can dance. Now let’s see if you can’.

And why was Akers called Angel? As he tells the story, during one of his engagements in a musical comedy show a well-known female actor (whom he declined to name) suggested he looked like the devil with his Van Dyke beard. As a result members of the company started calling him Lucifer, who according to the bible disguised himself as the Angel of Light. ‘Angel Akers’ was the long term result.

Bill Akers died in 2010. The extracts above are a minute part of an interview that documents many aspects of a long and varied career in the theatre. And like all oral history, it’s the voice that encapsulates the man—no longer ‘high and nasal’ but beautifully modulated and able to express in the most amusing way the most serious of endeavours.

Michelle Potter, 2 May 2012.

Here is the link to the National Library catalogue for the Akers interview. The National Library cataloguers have yet to add Akers’ year of death to the record. [This has been rectified—MP, 11 May 2012]

UPDATE August 2020: The interview is now available online at this link.