Rafael Bonachela is fond of giving his works Spanish names (he is after all a Spaniard by birth). Cuatro is Spanish for ‘four’ and Bonachela’s work entitled Cuatro consisted of four short solos for four artists of Sydney Dance Company. Each separate dance was accompanied by music played by a solo musician from the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Much of the creative development was conducted online with the final four outcomes filmed in isolation at the Sydney Dance Company studios in Ultimo.

Each dance was performed in a different space, beautifully designed and lit by Pedro Greig. Greig was also the film-maker. Each dancer wore a variation on a soft, flowing costume designed by Bianca Spender. The fabric colours ranged from very light grey through soft blue to golden yellow and each had some variation on a rolled and twisted design element, usually a part of the costume that crossed the shoulder.

Cuatro 1 was danced by Charmene Yap to an oboe accompaniment played by Diana Doherty. It took place in a confined space of three white walls.

Cuatro 2 featured Davide Di Giovanni performing to a violin accompaniment played by Andrew Haveron. The background this time was less confined with a draped back wall giving a softer look.

Cuatro 3 showed us Juliette Barton dancing to an accompaniment from Umberto Clerici on cello. Barton and Clerici performed in a black performing space that had three panels, made of what looked like small tiles, on each side of the space. The panels were lit with an exquisite golden glow, and often we saw dancer and cellist in shadow.

Cuatro 4 was performed by Chloe Leong with Emma Sholl playing flute. By the time we reached this fourth dance all walls had disappeared and Leong danced in a fine white mist that spread itself widely.

Choreography for all four solos was by Bonachela and each dancer showed his or her astonishing command of Bonachela’s movement style. This time I felt his choreography was slower and more liquid than usual and its qualities of introspection were deeply moving.

I began thinking of, and watching this series of solos as individual works. Each was released separately with a week between each. Eventually, I stopped watching this way and decided to wait until all four had been screened so I could watch the four in one viewing. I’m glad I did this because I’m not sure I would have had the same reaction had I just watched each a week apart.

I did have a favourite solo—that of Barton accompanied by Clerici. The filming was exceptional with its shadows and close-up shots. Barton was technically brilliant and I loved the way Clerici played his cello with his whole body and seemed completely lost in the sound. But what was wonderful about watching the four dances as if they were one work was that, for me anyway, an emotional underpinning emerged. The work began in that enclosed space with Yap sometimes touching the walls as if to highlight an inability to extract herself from the space. It moved to the possibility of emerging with the softer backcloth against which Di Giovanni performed. By Cuatro 3 the blackness of despair was there but the glorious lighting promised hope. By Cuatro 4 we had reached freedom.

Bonachela has always said his works can mean whatever we want them to mean. I love that. Beautiful work from the whole team

Michelle Potter, 20 August 2020

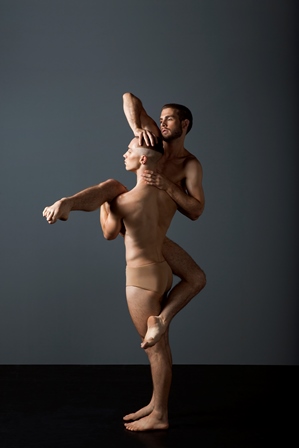

Featured image: Charmene Yap in a still from Cuatro 1. Sydney Dance Company, 2020