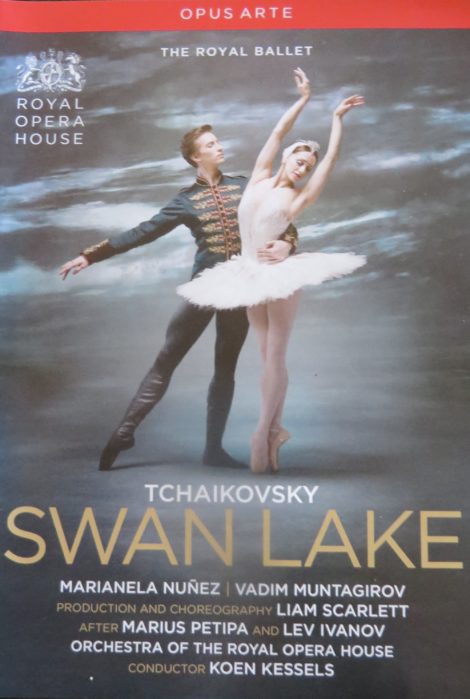

Friday 20 March 2020 (the day I began writing this) was the date I was to be sitting in the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, watching Liam Scarlett’s production of Swan Lake. Instead, with the world closing down as a result of COVID-19, I am sitting at home in Canberra having just watched a DVD of a 2018 performance of that production. Luckily I bought the DVD last time I was in London. I hadn’t had the chance to watch it until now. Here, then, are my thoughts.

Liam Scarlett’s production of Swan Lake is heart-stopping. I don’t think I can honestly say that of any other Swan Lakes I have watched over many decades of dance going. The main dancers—Marianela Nuñez as Odette/Odile, Vadim Muntagirov as Siegfried and Bennet Gartside as von Rothbart—not only dance with technical brilliance but project the underlying emotions of love, longing, loss, power and deception. Emotion pours out of every movement, every glance, every gesture. Powerfully.

Scarlett has made some choreographic changes, although they are not major. The production notes acknowledge Petipa, Ivanov, and Ashton as well as Scarlett. But some small non-choreographic changes that Scarlett has introduced make the storyline so much clearer. Many parts of the narrative we know just because we have read something, somewhere. But Scarlett explains things. He has an intellect and he transfers that intellect into the production, and hence to us. We are involved to a greater extent.

In Act I it is Prince Siegfried’s birthday and there is celebratory dancing. His mother the Queen (Elizabeth McGorian), acting a little sternly, suggests it is time for him to marry. But Siegfried decides to go out into the forest to shoot the swans he sees flying overhead. We know it all. We’ve seen it before. But are we ever really shown with clarity that it is Siegfried’s birthday? Or are we simply told that in the synopsis? In the Scarlett production, Siegfried’s friend Benno (Alexander Campbell) gives Siegfried a present, a golden goblet. And so begins the celebratory dancing, everyone with a goblet in hand for several moments. The Queen, when she arrives, also has a present for her son. It is a cross-bow, a family heirloom, and we know that Siegfried will use it in the next act.

It was also a change to see the introduction of an invitation, a paper prop clearly marked ‘Invitation’, to an event that would be held in the palace at which Siegfried would choose a marriage partner. It was shown to Siegfried by the Queen and his reaction paved the way for his anxiety, and ultimately to his going into the forest with his cross-bow.

But who was that mysterious rather supercilious man dressed in black who acted as some kind of adviser to the Queen? He seemed to be getting in the way a little and forbidding various things. Did he have the right? Well there was bit of dramatic irony introduced at this point. When, as Act I comes to a close, Siegfried goes against the wishes of the man in black and refuses to go inside, setting off instead with his cross-bow, the man in black drags himself upstage where he collapses as if shot. Is he von Rothbart in disguise? Has he been defeated in an attempt to keep Siegfried out of the forest where he might meet Odette? Or is this more a juxtaposition of innocence versus deviousness, good versus evil, with the Queen in the middle? Does it perhaps foretell von Rothbart’s end? It is simply exciting to ponder.

As the work transitions to Act II, the lakeside scenes (designs by John Macfarlane) are full of foreboding. A rocky outcrop and a bright moon dominate, although the lighting is quite dark. But then it is night time.

Throughout Act II there is the usual structure, perhaps with a little more mime than is apparent in many other productions. But what is transcendent is that Muntagirov shows us how he feels, anxious at times but full of longing for Odette. Nuñez shows her own anxiety, and perhaps fear. Should she engage with this man who appears to love her? Her technique, that beautiful line and her ability to unfold each movement slowly, is also a highlight.

We also meet von Rothbart as von Rothbart rather than the man in black of Act I. Macfarlane has given him a long feathery coat, reflecting the owl-like character of many productions, and has added a touch of red to part of his body costume: he is ‘red beard’ after all. Gartside gives a powerful performance with dominance as a major characteristic.

The work is set in Victorian times, clearly shown by the costume worn by the Queen in each of the acts in which she appears. But when Act III opens we see a kind of Baroque splendour. The sweeping staircase, extravagant floor lamps and the throne on which the Queen sits to watch proceedings all are reminiscent of European Baroque buildings.

Again Act III proceeds as one might expect, although the national dances have a real freshness to them and are beautifully (and I suspect expensively) costumed.

But once again Muntagirov stands out for the way in which he carries the story forward. From the longing and anxiety of Act II he is now thrilled at having found his lost love, or so he believes.

The coda from the Act III pas de deux is simply stunning. Marianela Nuñez’s fouettés, starting with a triple and sprinkled throughout with doubles and another triple, are remarkable, as are Muntagirov’s double tours finishing in arabesque. And there he is smiling all the while. Watch below.

In Act IV the lakeside scenic elements are clearer although the moon has disappeared somewhat. I guess dawn is approaching? The final pas de deux is heart-wrenching and I won’t introduce a spoiler and give away the deeply moving ending. Buy the DVD. It is worth every dollar and terrific watching, especially when everything live is currently cancelled.

As far as the DVD goes, it is interesting, too, to see Scarlett taking a curtain call with the company in this 2018 presentation. Everyone onstage looks and acts as though they have huge admiration for his work and for him. There is also an ‘extra’ on the DVD showing Scarlett and Macfarlane discussing their vision for the production. It is heart-breaking that Scarlett’s career, so remarkable to date, may be cut short by events currently being examined.

Here is a link to posts on this website about the works from Scarlett that Jennifer Shennan and I have seen and written about.

And as a final comment, of course I wish I had been able to see the work live. But …

Michelle Potter, 21 March 2020

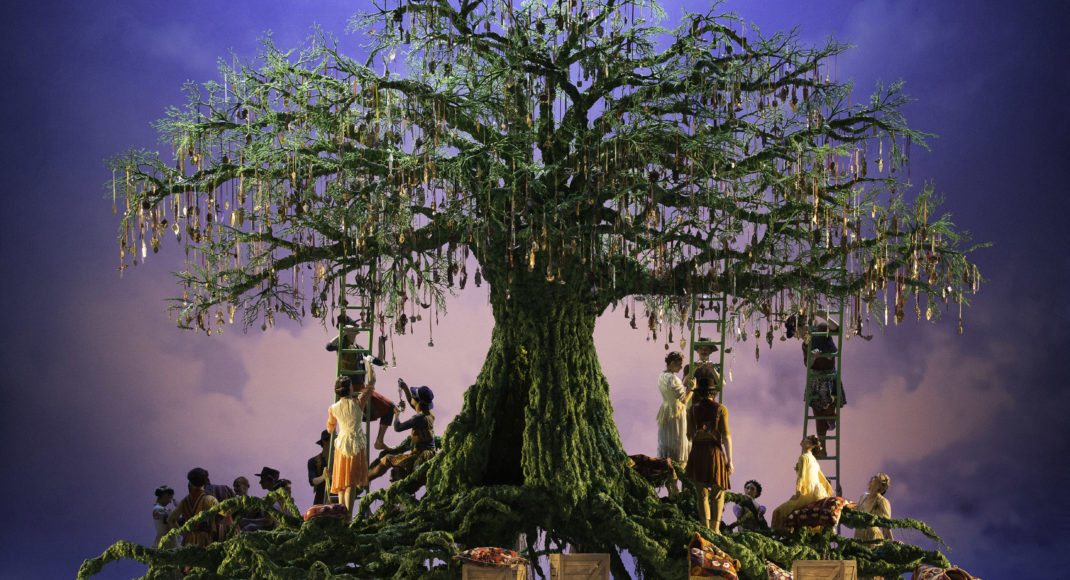

Featured image: Artists of the Royal Ballet in Liam Sarlett’s Swan Lake. © ROH, 2018. Photo: Bill Cooper