A recent streamed production by the Royal Ballet paid homage to George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, two American choreographers whose work over the course of the twentieth century was undeniably momentous. The stream began with George Balanchine’s Apollo, Balanchine’s first collaboration with Igor Stravinsky, which had its premiere in 1928.

This production of Apollo opened with the birth of the god Apollo, a section of the work not often presented, although it has been part of the structure of the work from its beginnings. Apollo’s mother, Leto, danced on this occasion by Annette Buvoli, is seen in labour and when we get our first glimpse of Apollo he is standing centre stage wrapped tightly in swaddling clothes. Two hand maidens begin to unwind the swaddling cloth until Apollo takes over and swirls out of the cloth. He is given a lute and the handmaidens help him pluck the strings, which at this stage of his life are unfamiliar to him. It has been a while since I saw this ‘birth and growth’ section and it is fascinating to see these stages in the life of Apollo condensed into a minute or so.

From these opening moments the ballet takes the form that is more familiar. Encounters begin between Apollo and the three muses, Polyhymnia (Mime), Calliope (Poetry) and Terpsichore (Music and Dance) who dance for and with Apollo until he eventually ascends Mt Olympus, called home by his father Zeus.

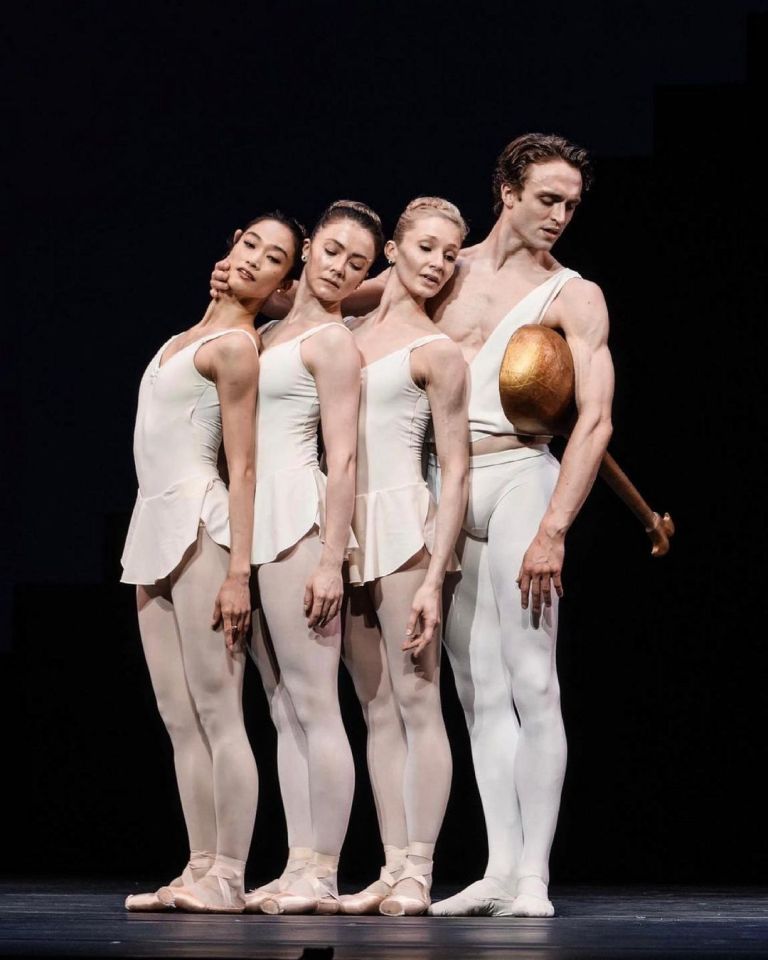

This Royal Ballet performance, however, was perhaps not the best Apollo I have seen. Somehow it lacked excitement especially from Matthew Ball as Apollo. I have always thought of Apollo as a somewhat flamboyant and influential character and Ball seemed to me to be rather too retiring (perhaps nervous?), despite his excellent technical accomplishments. For me, the most engaging performance came from Fumi Kaneko as Polyhymnia. She entered fully and easily into the dramatic nature of the character, and her role in the unfolding story was easy to follow.

But Balanchine’s choreography for Apollo is always a joy to watch with its beautiful groupings and poses and its use of rounded and enfolding arms that prefigure the fluidity of Balanchine’s later choreography for his corps de ballet in various of his works. Other sections, including those movements from the Muses where they turn on pointe but with bent knees, always make me think of how challenging Apollo must have been for audiences (and dancers?) in 1928.

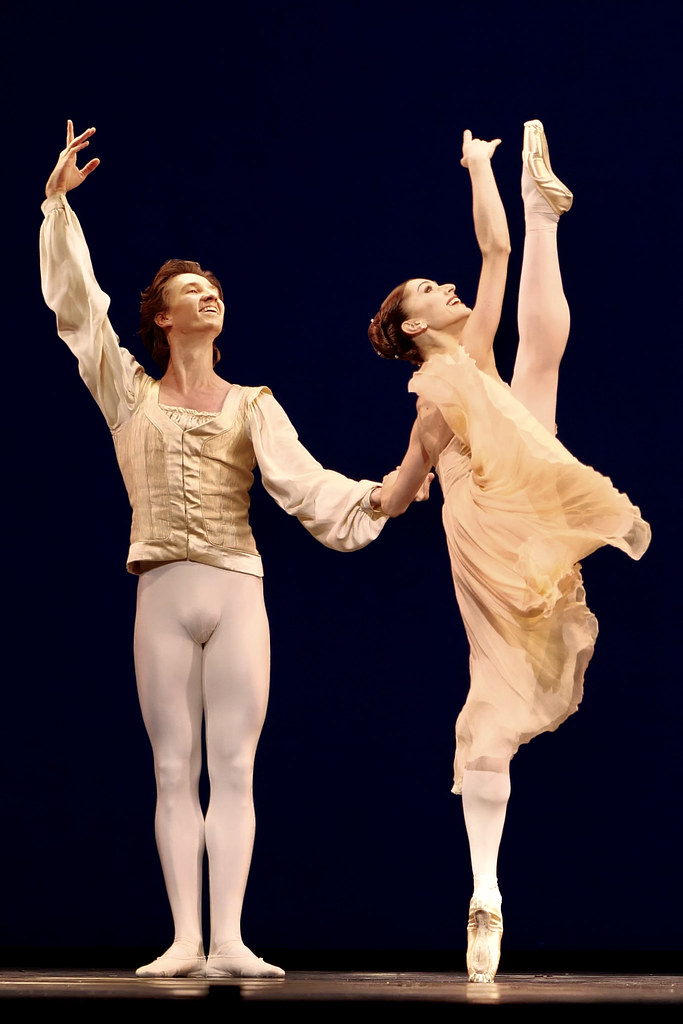

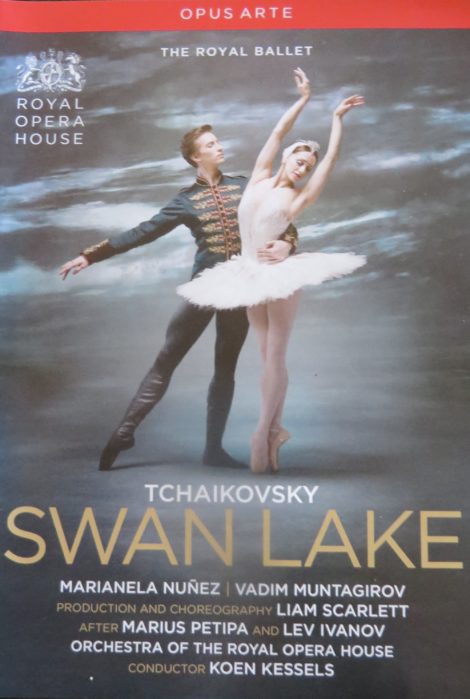

The absolute highlight for me on this program, however, was the second item, Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky pas de deux, danced by Marianela Nuñez and Vadim Muntagirov. It was ballet at its finest in terms of crowd appeal and Nuñez and Muntagirov have the strength of technique to make those show-stopping movements look easy. It was also totally transfixing to watch the joy they exhibited as they moved, and the way they engaged with each other throughout (even in the curtain calls). They were just brilliant.

The program ended with Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a gathering. I watched the Royal Ballet’s production of this work in October 2020 and reviewed it then so won’t review again other than to mention the beautiful performance by Fumi Kaneko as the Green Girl. Kaneko, who was promoted to Royal Ballet principal last month, danced with such joy and such apparent ease that it was impossible not to be moved and thrilled, as I have been every time I have seen her dance.

Michelle Potter, 03 July 2021

Featured image (shown below in full): Vadim Muntagirov and Marianela Nuñez in Tchaikovsky pas de deux. The Royal Ballet, 2020. Photo: © Rachel Hollings