8 & 9 April 2021. Bruce Mason Theatre, Takapuna, Auckland

Auckland Arts Festival

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

This long-awaited premiere season of a new contemporary ballet company, BalletCollective Aotearoa, was nothing short of a triumph. Come the curtain-call, many in the sizeable audience were on their feet to salute the choreographers and composers, the dancers, musicians and designers, the courage and commitment—the whole fresh resilient New Zealand-ness of it all. Many are in the team but artistic director and producer, Turid Revfeim, is responsible, and deserves acclaim.

Revfeim has led her stalwart little troupe of dancers in and out, around and back through the Covid-induced challenges and shadows of these past many months. They must have walked close to the edge more than once, as funding began then disappeared (the Minister of Arts might ask questions about that), lockdowns descended (‘Just do the right thing and stay home’), schedules postponed (‘Well, let’s just re-schedule then’), flights and accommodation booked then cancelled (‘OK, let’s just re-book then’), ‘Let’s just abandon the project since there’s no budget and it’s so hard to keep going?’ (‘Never, never, never. We will dance’). ‘Intrepid’ and ‘indomitable’ are the adjectives they have earned.

There were shades of 1953 and the pioneering endeavours of Edmund Hillary, or perhaps I mean Poul Gnatt, as the performance got under way. The intensely passionate and utterly stunning musicians of New Zealand Trio were right there, just off-centre, upstage left, for the whole performance. By that staging, the three separate choreographies on the program merged as a trefoil of faith, a shamrock of hope, a clover of charity. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. J. S. Bach walked 400 miles to hear a concert. I only had to sit on a plane for one hour.

There is an impressive interview with Turid Revfeim on RNZ Nine to Noon, 9 April, (the podcast on RNZ website is well worth listening to), which sets the background and context of this courageous ballet initiative. If you think this is a rave review of the performance and of the entire enterprise, you are right.

The opening work—Last Time We Spoke—by Sarah Knox, to composition by Rhian Sheehan, was an abstract yet poetic treatment of themes of how to be alone together. The cast of six dancers in fluid pairings across several sections of the work found connection in the lyrical music to make friends with consolation and memory. Tabitha Dombroski and William Fitzgerald were striking among the cast of six dancers.

Helix, the second work by Cameron Macmillan, one of New Zealand’s ex-pat choreographers whose work we all want to see more of, borrowed its title from the music, Helix, composed by John Psathas, leading New Zealand composer. It was preceded by an excerpt from Island Songs, a different composition by Psathas, a staggeringly virtuosic challenge to musicians who rose to every thrilling, throbbing quaver of its melodic percussion.

In Helix, the drama continued as Macmillan traced a journey, not exactly narrative but with suggestions of story nonetheless—a woman, a man, and shades of relationships between them. Some woman. This was the phenomenal Abigail Boyle who is quite simply the leading ballet dancer in the country, no contest. Just standing still she is dancing, such is her sense of line and presence, but when she moves, o my. Her investment in the role as she journeyed round the corners of the stage carrying her chair, and through the centre of the stage as she contained emotion in her every movement, was a deeply anchored yet airborne performance. Boyle is a national treasure of dance in New Zealand and we are overjoyed to see her performing still at the peak of her powers. William Fitzgerald partnered her with a strong and sensitive quality that reminded us of his dancing which has also been much missed here of late. Tabitha Dombrowski and Medhi Angot were powerful among the committed cast of eight performers.

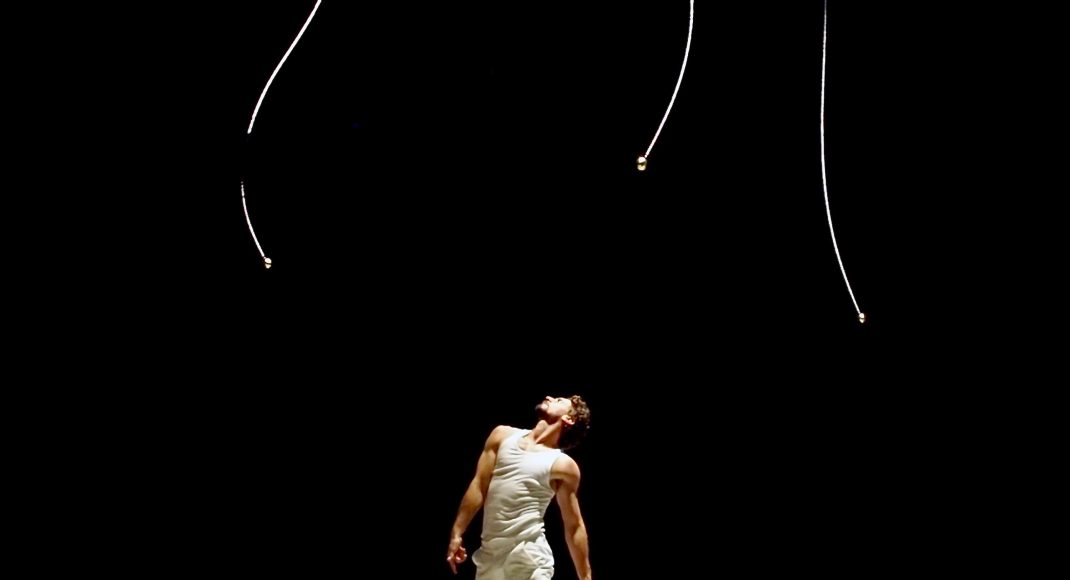

The third work, Subtle Dances, choreographed by Loughlan Prior, composed by Claire Cowan, takes its title from the music, which in turn becomes the title for the triple-bill as well. Prior and Cowan are a pairing of major talents. The work explores and explodes with themes of gender blurring—swirls of hot tango as the boys and girls and boys come out to play. It is saucy, spicy, dark and compelling. Complex courtships, allusion alternating with illusion, remind us of nature’s best dancers. It invites searing performances from all the cast, and confirms this BalletCollective Aotearea as a troupe of striking dance talent, in fabulous collaboration with the phenomenal musicians of the New Zealand Trio.

As soon as the box office opens for their next season we will be in the queue, however many hundred miles of travel that might mean. Here is a link to the RNZ podcast featuring Turid Revfeim.

Jennifer Shennan, 10 April 2021

Featured image: Scene from Loughlan Prior’s Subtle Dances. BalletCollective Aoteraoa, 2021. Photo: © John McDermott