I didn’t see Graeme Murphy’s 2017 work, The Frock, as a live production. It was fashioned by Murphy and his creative associate Janet Vernon on the Tasmanian group of ‘senior’ dancers, Mature Artists Dance Experience (MADE), a company I have never had the luck to see live either. But some research I have been doing recently aroused my interest and I found a way to see The Frock on film. And what an adventure it was!

The Frock follows the life experiences of a woman who sits at the side of the stage on what looks like the verandah of a house in a rural area of Australia. She watches as her life unfolds before her, although leaves the comfort of her verandah to participate in many of the experiences that play out on stage. She is nameless and is something of an ‘everywoman’ living across several decades, beginning perhaps in the 1950s.

But before those decades begin to unfold choreographically, in the opening section the woman explains the moments that define her situation, especially the dress made by her mother, the frock of the title; and her sexual experience as a teenager (wearing the frock), which resulted in an out-of-marriage pregnancy. Throughout the work the frock appears on a wire mannequin designed by Gerard Manion. The mannequin is a mobilised device (robotics by Paul Fenech) with a voice (that of Murphy) that comments verbally, not always kindly, on what is happening.

The first moment of remarkable dancing comes when the frock is tried on for the first time. We watch as the woman (in real life and in the story in her sixties perhaps) dances a duet with another performer representing the woman as a young girl wearing that frock. Murphy’s choreography is lyrical and emotion-filled movement; not a collection of difficult steps but swinging, swaying movement easily fitting the bodies of those older dancers. It is also the first time we see the backcloth (design by Gerard Manion) that stayed in place for most of the show—a beautiful collection of draped fabrics, lit throughout by Damien Cooper.

From there the decades unfold before us: the ‘swinging sixties’ and seventies, along with the smoking of drugs and the hallucinations that resulted; the rise of feminism; midlife; and the gradual move through the following decades to old age, the ‘Age of Invisibility’. Choreographic highlights included, for me, the rock ‘n roll scenes; the section when the woman contemplates her childless life; the beautiful reunion scene in which the woman and friends from her past come together dancing to Moon River, that evocative song from Breakfast at Tiffany’s; a trio as mid-life approaches danced with the aid of lengths of diaphanous cloth; and the extraordinary solo by the woman performed to a poem (written by Murphy) entitled ‘But still I fly’. The poem is heard in the clip below, along with excerpts from various parts of the work.

It was fascinating to see Murphy using some of the techniques that have appeared in so many of his works, including the use of flowing cloth as a device. But also noticeable was the use of linked arms and hands making linear patterns, something that I recall from many of Murphy’s works with Sydney Dance Company. Then there were references (that perhaps I imagined) to Botticelli’s ‘Three Graces’ in his well-known painting Primavera, and even, briefly, to Nijinsky’s choreography for Afternoon of a Faun. (Murphy does this so many times—brings up a mixed bag of ideas, imagined or not).

The sound design by Christopher Gordon with Christo Curtis was brilliantly put together to evoke every moment in every decade. Apart from Moon River, standouts for me were the Sunday School activities of the early moments when the hymn being sung was that well-known Sunday School song, Jesus Loves Me; the Indian inspired music that accompanied the drug and hallucination scenes; and some hugely moving operatic excerpts.

Jennifer Irwin’s costume were also so evocative of the decades being represented as the story proceeded. Especially outstanding from this point of view were those in the scene taking place in the 1960s filled, as it was, with mini-skirted dresses in brightly coloured, floral fabric, sometimes matched with knee high boots in bright colours. How it takes those of a certain age back to their own teenage years.

The Frock might be counted as one of Murphy’s most theatrical productions with so many exceptional collaborative elements, including its hugely diverse selection of musical interludes; its poem ‘But still I fly’; and its robot carrying the storyline line along. But perhaps more than anything it arouses such a range of emotions in the viewer. That to me is theatricality at its best. Sometimes The Frock is quite simply confronting. At other times it is just hilarious. But more than anything it is deeply moving as a comment on life’s many changing situations. I have to admit I started to cry at the end as the woman, and the daughter she had never met, intuitively knew who the other was when they came together unexpectedly in an op shop where both admired that frock hanging on a rack of clothing on sale. But the weeping quickly turned to laughter as the dress was shoplifted out! Magnificent Murphy.

Michelle Potter, 22 August 2021

Featured image: Scene from The Frock. MADE 2017. Photo: © Sandi Sissell

Postscript: I should add that a complete version of The Frock is not publicly available at this stage, although a promo is available on Vimeo, beautifully put together by Philippe Charluet of Stella Motion Pitures.

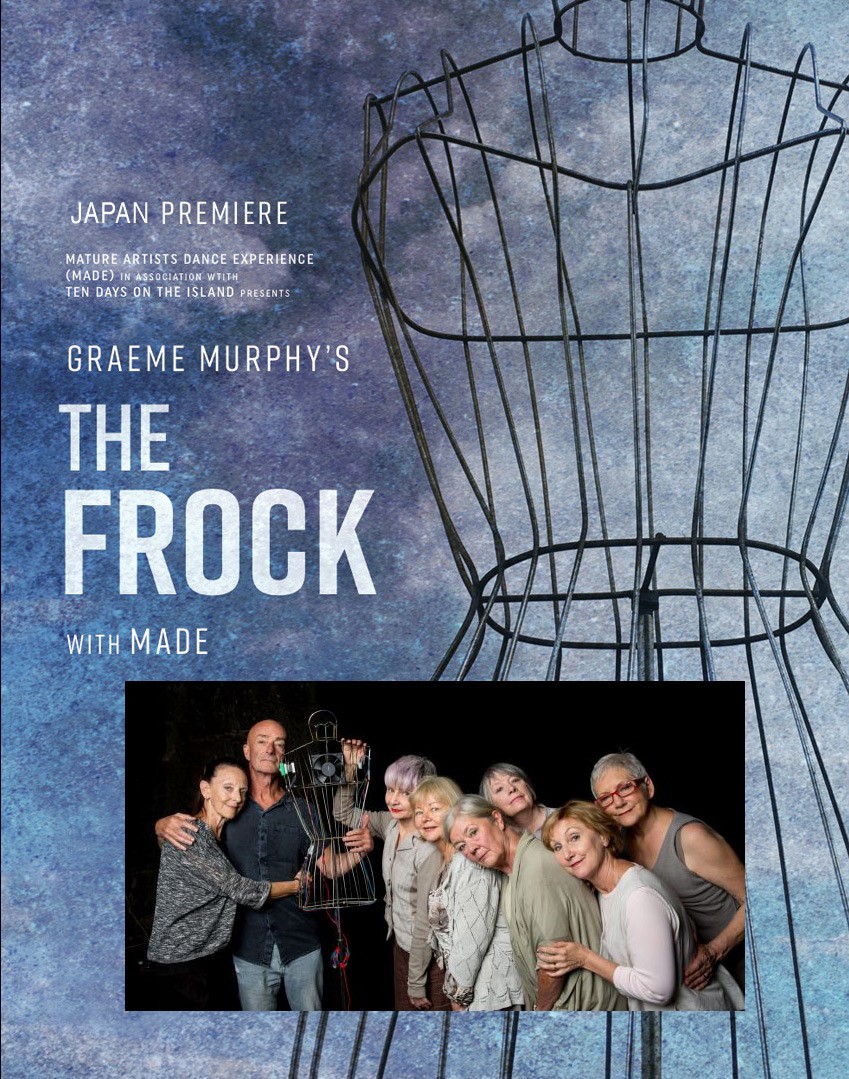

The poster image below announces the premiere of the work in Japan in 2018.