9 December 2023 (matinee). Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

There’s nothing like being there!

My first impressions of David Hallberg’s vision for a new Swan Lake were not entirely positive—but I saw it first on film. My second viewing was a live performance and, while the stage of the Joan Sutherland Theatre is really too small (as we have all known for years) to stage a fully successful production of any large scale ballet, being there rather than watching ‘from the comfort of my own home’ gave me a new and more positive impression.

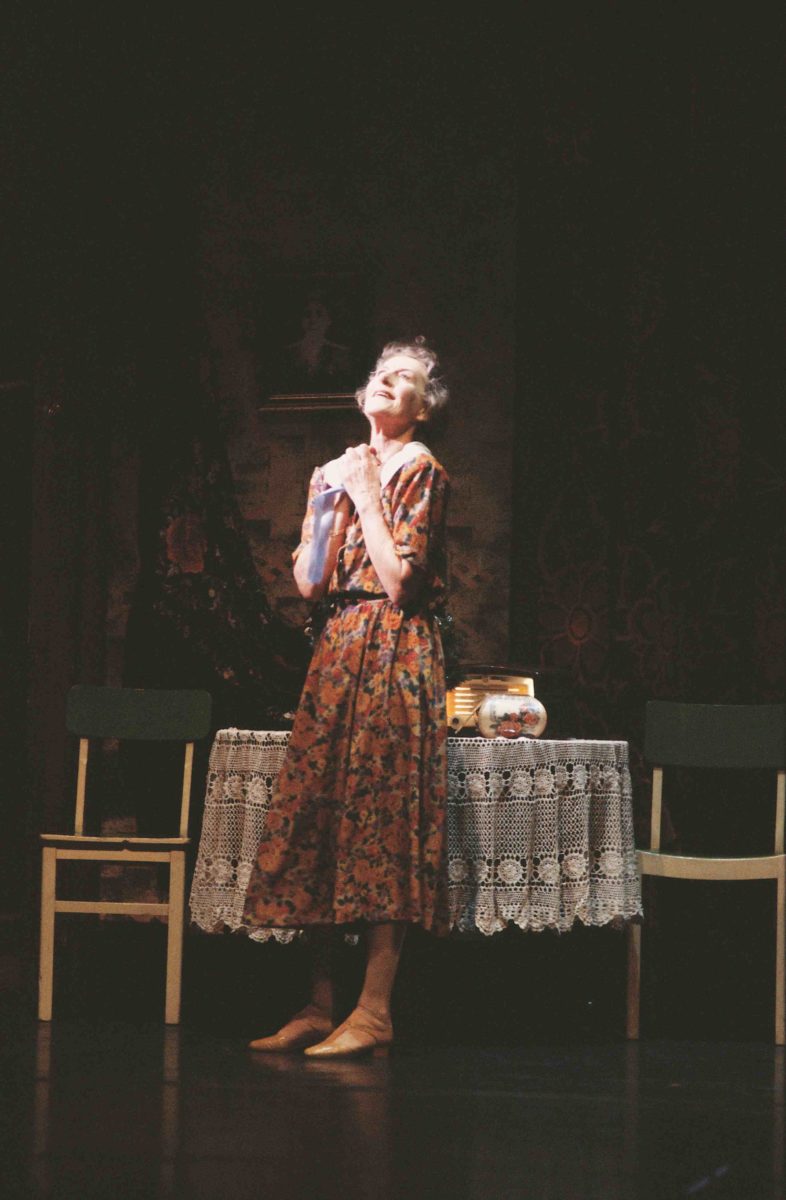

In Act I, following an interesting Prologue in which we learnt of the long-standing role of von Rothbart, the dancing from those gathered to celebrate Prince Siegfried’s name day was joyful and just gorgeous to watch. As often happens, my eye was drawn to Joseph Romancewicz* who always seems to inhabit the role he has taken on, even when it’s simply a character in the corps de ballet. But everyone in the corps of dancers looked and performed just beautifully. Nathan Brook as Siegfried was suitably withdrawn as he pondered his future, although his solo, which concludes the first act, was a little shaky in parts. It would have been a stronger Act I, however, if the Queen Mother (Gillian Revie) had had more dominance in the unfolding of the narrative. She seemed almost superfluous.

Unfortunately however, my original thoughts on Act II didn’t change much with the stage performance I saw. The dancing, especially from the corps de ballet and soloists, was exceptional but there was still little emotion on display, including from Dimity Azoury who danced Odette. I have never seen Act II of Swan Lake danced with the coldness, or apparent lack of emotion, that seems to be what is required in this production. Why is it like this? Very disappointing.

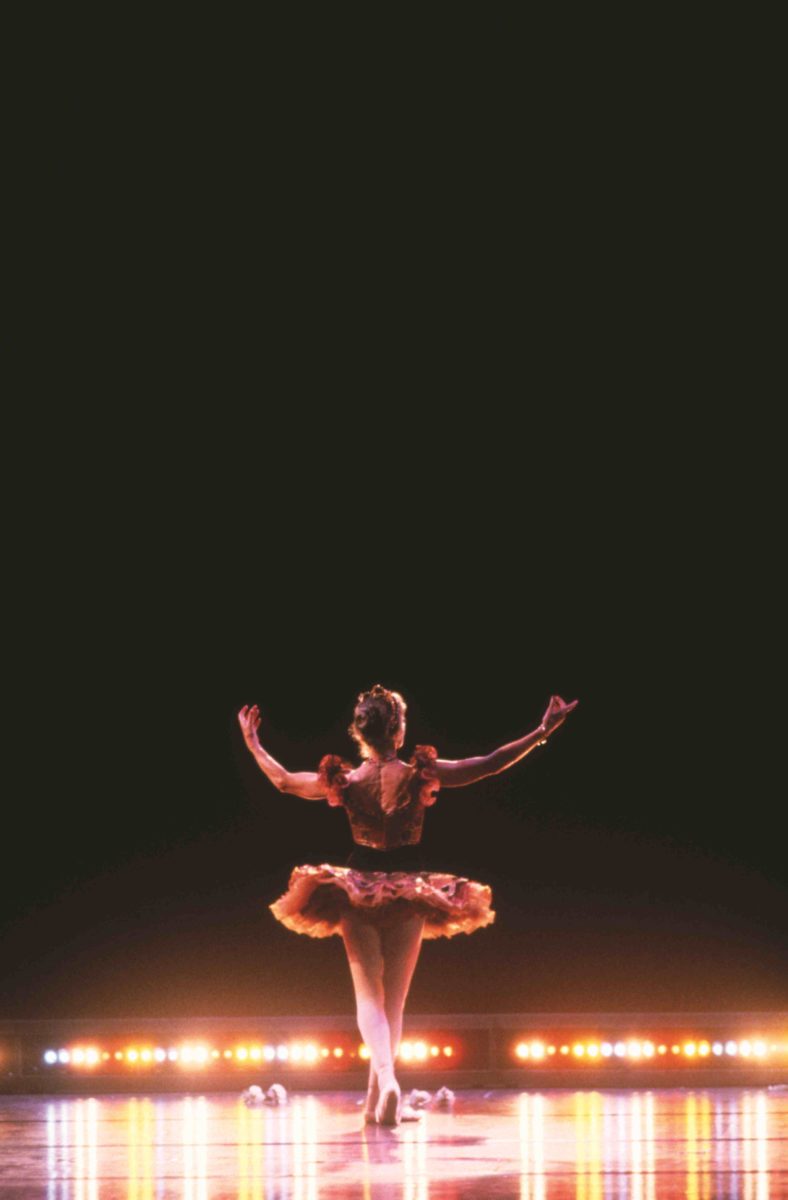

Things changed a little in Act III. The national dances were more spirited than what I saw on film and both Odile and Siegfried were more believable as characters, even if Azoury as Odile needed to be more seductive (rather than just smiling out at the audience). Sadly too Azoury’s 32 fouettés were somewhat out of control.

The last act, however, was quite stunning. I was transfixed by the beautifully minimal aspect of the choreographic structure, and how the dancers’ performance made this structure very clear. I also loved the way the four little swans and the two leading swans (Isobelle Dashwood and Saranja Crowe) were so clearly included in the group sections of the choreography in this act. In addition, the unfolding of the story in this final act was very clearly shown and, to my immense pleasure, there was at last some measure of emotion between Odette and Siegfried, especially noticeable from Brook’s strong input in relation to his feelings for Odette and for his betrayal of her in the previous act. What a difference a bit of emotional input makes!

As for the curtain calls, they were distinguished by the loud boo-ing that greeted von Rothbart (Jarryd Madden) as he entered to take his call. A real accolade for Madden’s fine interpretation of von Rothbart especially in Act III where his belief in his superiority (even to the extent of his sitting in the vacant chair next to the Queen Mother), and his absolute single-mindedness that Odile would triumph, were very clear.

And as a final point, the orchestra, led by Jonathan Lo, was in fine form. We could almost see the music and hear the choreography so well were they together.

Michelle Potter, 11 December 2023

Featured image: A choreographic moment from the corps de ballet in Swan Lake. The Australian Ballet, 2023. Photo: © Daniel Boud

*Joseph Romancewicz danced von Rothbart at some performances. I regret that I didn’t see him in that role. I’m sure he would have made it his own!

Postscript: One of my recent second-hand purchases was a book I previously never knew existed: Misha. The Mikhail Baryshnikov Story (London: Robson Books, 1989) by Barbara Aria. In it the author talks about the Baryshnikov staging of Swan Lake for American Ballet Theatre. Speaking of Swan Lake as brought out of Russia in annotated form by Nikolai Sergeyev, Aria writes on p. 175, ‘It was these contemporary Soviet versions that Misha restaged at ABT, adapting and streamlining them in the process.’ While Hallberg was not part of ABT when Baryshnikov was leading the company, I can’t help wondering whether there is some influence from the ‘adapting and streamlining’ that Aria suggests characterised the Baryshnikov ABT production (which perhaps was also there in subsequent ABT productions?) in the ‘boiled down and refined’ production that Hallberg was seeking, which I mentioned in my previous review.

In the same book the author quotes from a review by esteemed New York-based dance critic Joan Acocella. Writing on p. 197 on Baryshnikov’s portrayal of Siegfried in Swan Lake’, Acocella is quoted as saying, ‘[Baryshnikov’s] mere shoulder, seen from behind, told you everything you need to know about the Act III Siegfried: that he’s a prince, that he is in love, that he is in doubt.’ There it is—the way in which simple movements can portray aspects of narrative!