Reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The New Zealand Dance Company’s Lumina has just toured to five centres in the north island—one performance in Whangarei, in Mahurangi, Napier, Wellington, New Plymouth—after a premiere season last year of the same program in its home base, Auckland, and appearances earlier this year at the Holland Dance Festival—where incidentally Black Grace also performed.

The company has been performing since 2012, with the dancers recruited on a project base, rather than employed on continuous contracts. There are eight dancers in the company, all of them strong, svelte and with refreshingly individual qualities. Six are graduates from Unitec in Auckland and two are from New Zealand School of Dance.

We saw NZDC’s Rotunda last year, with the New Zealand Army Band sharing the stage. The three works on this program are choreographed by Dutch/American Stephen Shropshire, and by New Zealanders Louise Potiki Bryant and Malia Johnston. The works result from a specific commission ‘to engage with light, illumination, space, image, movement’.

To some degree of course all choreography does do that—with music usually the defining part of the equation. In this program though, many graphic effects are sourced by playing with light at various levels, which creates some striking sculptural images. So in a way the evening is more visual than aural, though the music for one work does guide and follow the development of the choreographic structure in an interesting way.

The Geography of an Archipelago, by Stephen Shropshire, makes analogy of the physical isolation of an island, or string of islands, with a human or group of humans. A huge sculptural triangle is slowly transported about the stage, with the resulting shadows suggesting spaces, real and imagined, that isolate individuals. Some dancing in a pocket of light engages us, then we perceive that a similar sequence is being danced parallel in the dark. How alike we are, how separated we are. The movement has strong contrast between a dancer’s limbs and his torso, as if striving to belong together. The dancers’ ceaseless tramping of feet in another section seems to take us journeying with them.

The work integrates well with the music by Chris O’Connor, his driving percussion leading to Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, then sighs, bells and taonga puoro to suggest opposite ends on the spectrum. One dancer playing a quiet conch implies live music is closer than you think, echoing the ‘meandering journey towards oneself’ from the program note. In this strong and confident choreography, Xin Ji dances with an electric clarity that becomes poetry. A sudden blackout ended the work whereas a slow-motion quiet fade would have suited me better, but I can imagine that for myself.

In Transit, by Louise Potiki Bryant, is a powerful and poignant choreography. Long sticks are used as props, suggesting weapons of defence and attack, of palisade and territory marker. It is not a narrative in the obvious sense, but there are numerous references to the memories of past encounters that Maori have experienced within and between groups. Posture dances but with lyrical rather than forceful limbs are hinted at. A telling female figure in red in the background is a grieving witness to the many incidents obliquely referred to. Numerous stylized images of human forms are projected on to screens and moving bodies, in metaphors that suggest experiences among preceding generations and memories of history.

Tupua Tigafua and artists of New Zealand Dance Company in In Transit. Photo: © John McDermott. Courtesy New Zealand Dance Company

Brouhaha (a trope from early times used ‘to warn of the devil disguised as clergy’) is Malia Johnston’s whirlwind work that pitches speed of dance movement against the projected lighting effects which build exponentially with the sound throughout. A plethora of light lines travels across the set and connects to the busyness of the soundscape. Extreme stamina is demanded from the dancers throughout—close to exhaustion, they certainly earn the ecstatic and beautiful choral cadence of reaching heaven after such a hard time on earth but it was tantalisingly brief. We needed that too to last longer…

Each of the three works has strong choreography, wide ranging visual effects with light and shade, and performances in tight tandem. Overall it is sophisticated, and the graphic effects tethered to electronic sound will be exciting for some, but I found at times that these elements of moving light spectacle almost overpowered the dancers’ presence. It’s good to think of them performing in New Plymouth where Len Lye’s kinetic sculptural work, overlapping with dance movement, is housed.

Program notes are an opportunity for a choreographer to speak in clear prose, the thoughts and concerns of a work. It is pretentious to claim that we should be left to make our own sense of what we see. Of course that is exactly what we do—but a program note is just like an abstract, précis, synopsis, introduction, commentary, caption or storyboard. Such forms have a clear function and need to use specifics, not to philosophise in generalisations or universals if they are to fulfill their purpose. I often find this an area for improvement in dance productions these days.

This is a well-resourced national dance company so it’s a pity there was only one performance in each venue since considerable technical set-up is involved and one assumes that the touring itself is the major outlay. A second performance would allow word of mouth, always the best publicity, to filter through. Most of all, if the performance is astonishing, you can go back for a second viewing. I would certainly have wanted to see the opening work a second time, to savour its dynamic integration of choreography with music.

An aside: I saw a few weeks ago a screening at the New Zealand Film Archive of Douglas Wright’s work, Now is the hour, from 1988. It is extraordinary and insightful choreography, and wonderful that the work has been so skilfully filmed. Shona McCullagh, now artistic director of the NZDC, is in the cast and moves with very great grace. Dance is such an ephemeral art. Anything to save and savour its repertoire is to be treasured. It shows us where we were and where we are going.

Jennifer Shennan, 25 May 2016

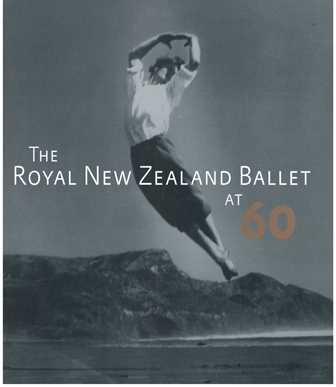

Featured image: Artists of New Zealand Dance Company in a study for Lumina. Photo: © John McDermott. Courtesy New Zealand Dance Company