16 May 2024. The Playhouse, Canberra Theatre Centre

Below is a slightly enlarged version of my review of Subject to Change, which was published on 17 May in Canberra CityNews.

Three separate works made up Subject to Change, the 2024 production by Quantum Leap, the pre-professional youth performance group at Canberra’s QL2 Dance. First up was Kaleidoscope choreographed by Gabrielle Nankivell, then came Alpha Beta from Alisdair Macindoe. Both Nankivell and Macindoe are professional choreographers with extensive experience across Australia and overseas with much to offer young dancers. Voyage was the third work on the program and the final work from current artistic director of QL2 Dance, Ruth Osborne, as she prepares to hand over the directorship to Alice Lee Holland.

The overarching theme of the evening was the effects of a rapidly evolving world and the need to adapt to changing conditions. Not all works were easily or instantly understood within that theme, but the standard of dancing was exceptional, as was the overall theatricality of the production, especially in terms of the lighting design from Antony Hateley and the film input from Wildbear Digital.

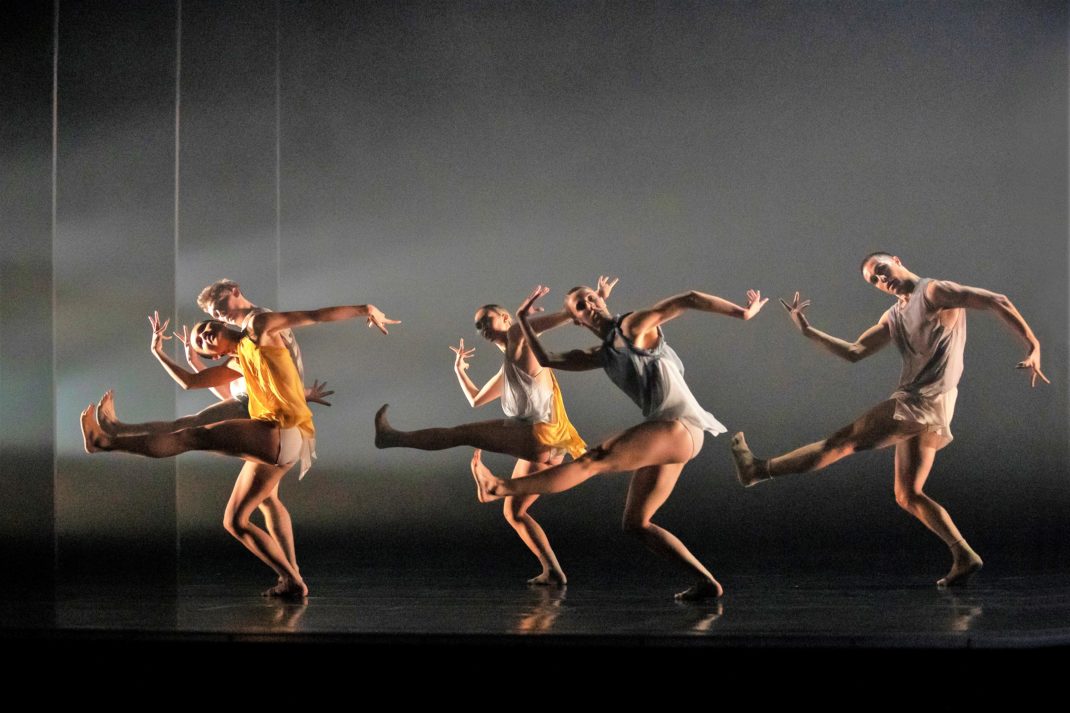

Nankivell’s Kaleidoscope was structured in a series of short sections, each separated by a sudden blackout. It focused on negotiating change and contained what was probably the most complex choreography of the evening. The dancers had to move on and off stage with speed and the work contained a vast array of choreographic patterns, all filled with what was also a vast array of movement. One of the dancers I spoke to used the word ‘wild’ (without in any sense condemning the work) to describe the choreography. The movements were often quite intricate and sometimes unexpected and certainly required an ongoing and strong input from the dancers. It was performed to a score by Luke Smiles and, given the speed and complexity of both music and choreography, the ability of the dancers to give the lively performance that they did was outstanding.

Macindoe’s Alpha Beta, performed to a score by Macindoe himself, was second on the program and looked at concepts of individualism and collectivism. After the fast-moving Kaleidoscope, Alpha Beta seemed, at least initially, quite static with the dancers often standing still or engaging in sharp movements of the arms into positions that they held fixed for a few seconds. While it ended with the dancers engaging in a kind of rave, which was in opposition to the stillness that permeated the early sections, for me Alpha Beta wasn’t quite so engaging as the previous work.

The final work was Osborne’s Voyage, which in true Osborne fashion was clearly structured in terms of a strong and varied use of the stage space and a constantly changing arrangement of groupings of dancers. Performed to music by long-term collaborator with QL2, Adam Ventoura, Voyage examined the experience of change, often in an emotionally moving way. It was probably the most clearly understandable of the three works in terms of giving an insight into the overarching theme. This was most apparent when on a few occasions the dancers came together in a single line across the stage and appeared to be examining their individual responses to change.

Voyage was enhanced by some exceptional film footage created by WildBear Entertainment and used as a kind of backcloth. What made it special was that it had been edited in an engaging manner to be seen not as a series of single frame shots, but sometimes as a collection of two or three different moments of footage placed side by side, or as a series of mirror images of one particular section of footage.

Costumes were by Cate Clelland. also a long-term collaborator with QL2 Dance. As with her previous costumes for Quantum Leap programs, they were simple but effective in design and in the use of colour.

Subject to Change was one of Quantum Leap’s strongest productions and a fitting farewell to Ruth Osborne who has been at the helm of QL2 Dance since the beginning of its existence some 25 years ago. The list of alumni that Osborne has taught and mentored and who have gone on to make a career in dance is quite simply incredible and some of those who danced in Subject to Change are very likely to join the list.

Michelle Potter, 18 May 2024

Featured image: Scene from Kaleidoscope in the Quantum Leap program Subject to Change. QL2 Dance, 2024. Photo: © Olivia Wikner