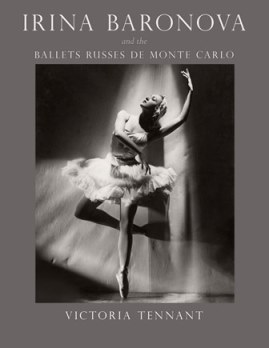

Victoria Tennant is the elder daughter of Cecil Tennant and Irina Baronova, the latter so well-known in Australia where she first charmed audiences with her dancing in 1938 with the Covent Garden Russian Ballet, and where she also spent her last years in a beautiful house at Byron Bay, New South Wales. Victoria Tennant, of course, knew Baronova in quite a different role from her legion of Australian fans: ‘Our mother was devoted to us,’ she writes, ‘and not exactly like anyone else’s mum. No one else’s mum did pirouettes in the butcher’s.’ This observation perhaps encapsulates the tenor of this book: it is a very intimate memento built around a personal collection of letters, photographs and other archival materials.

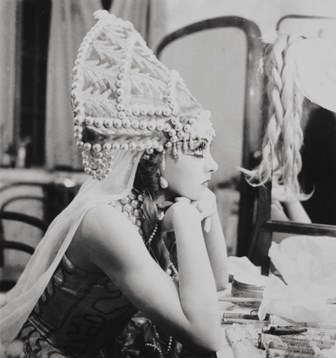

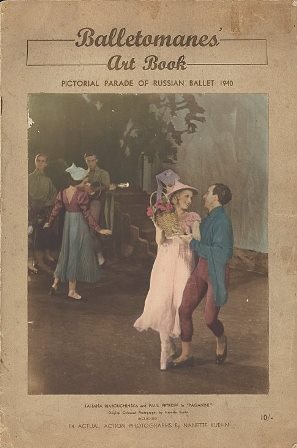

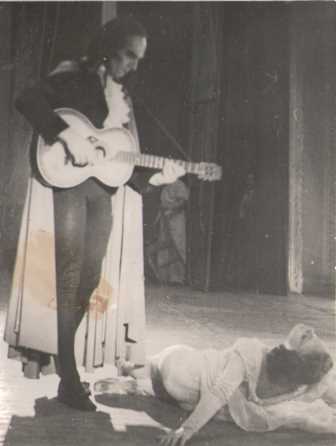

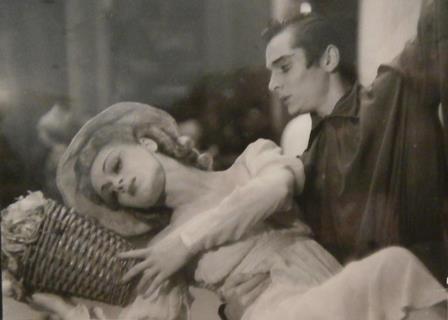

What is especially attractive about this book is its extensive use of photographs, which have been drawn largely from Baronova’s own collection. Many have never been published previously. Some are glamorous shots from Baronova’s Hollywood years. Others are informal shots of family and friends. Yet others are lesser known shots and early images from ballets in which Baronova starred.

Images from Irina Baronova and the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo by Victoria Tennant: clockwise from top left, Baronova in the movie Florian, 1940; driving with friends from San Diego to Los Angeles, 1936; in costume for Le Spectre de la rose, 1932; in costume for Thamar, 1935.

The book also has a special quality because much of the text consists of quotes from letters, an oral history made for the New York Public Library’s Dance Division, and recorded conversations made by Baronova at various times, although, unfortunately, it is not always clear which source is being used. But the informal voice of Baronova is strong. Anyone who met her, however briefly, or saw her speak in public, or teach or coach, will recognise that the words are hers and will be charmed all over again. These sections are differentiated from the linking text, written by Tennant, by the use of a differently coloured font.

There are some beautifully insightful moments when Baronova talks about working with various choreographers in different ballets. I was especially taken by her comments on Les Sylphides.

Nobody realizes that in Les Sylphides the whole thing is a dialogue between the Sylphides and the invisible creatures of the forest. It’s a whispering talk. All the gestures are listening, questioning, whispering back. It’s a conversation, and the Sylphides turn in the direction of the voice they hear and run to it. If you don’t know that, there are no reasons for doing anything, it’s just empty and boring. The whole ballet should be acting and reacting. To do it any other way is not fair to Fokine.

The chapter on Baronova’s time in Australia, 1938–1939, is short. But much has been written now about that time in Australia’s ballet history (although the last word has not yet been said I am sure) and the book is balanced in its coverage of the many strands of Baronova’s life. From a reference point of view it is good to have a list of Baronova’s repertoire from 1931 to 1946, although it is a shame that her film roles are not included as well.

Irina Baronova and the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo has been beautifully designed and produced and, with its strong focus on imagery, makes a wonderful companion to Baronova’s autobiography.

Victoria Tennant, Irina Baronova and the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2014)

Hardback, 244 pp. ISBN 978 0 226 16716 9 RRP USD55.00/£38.50.

Michelle Potter, 1 November 2014