26 August 2012, Playhouse, Queensland Performing Arts Centre, Brisbane

John Neumeier’s Nijinsky is an unusual work and defies easy categorisation. It is neither an abstract nor a narrative work. It’s more like a series of pictures that unfold throughout the work, building to a huge climax in the second part. Those pictures represent random events in the life of Vaslav Nijinsky and are really a series of flashbacks presented to reflect his diagnosed schizophrenic condition. They begin as he prepares to give his final dance performance—a Red Cross benefit show at the Hotel Suvretta in Saint-Moritz, Switzerland.* Neumeier uses this flashback technique to explore many different facets of Nijinsky’s life. We encounter him as a brother and a son, a dancer, a lover, a choreographer, a husband, and we are given impressions of the emotional states that accompany those roles in his life. Not only are these flashbacks random pictures, they also push us headlong into a maelstrom as they combine together, out of historical and any logical sequence and in a surreal fashion. Neumeier calls it a ‘biography of the soul’.

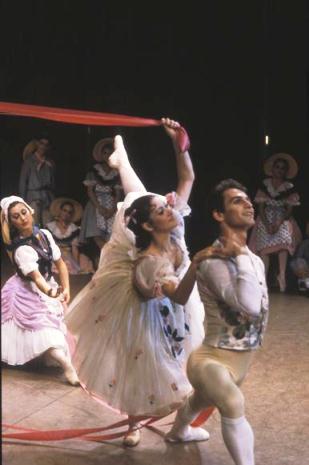

There are some thrilling moments of dancing. The trio between Nijinsky’s wife, Romola (Anna Polikarpova), Nijinsky (Alexandre Riabko) and Nijinsky as the seductive Faun (Otto Bubenicek), in which Neumeier explores facets of love and desire and life and art, is one such moment. The trio between Diaghilev, Nijinsky and another young dancer, where we see the destructive power of Diaghilev, is another. But for me the most powerful moments come in the second part of the work, when Nijinsky feels attacked from all sides—his schizophrenia is a reality, the Great War begins, his brother Stanislaw dies, Massine takes his place in Diaghilev’s life and activities and Romola has a liaison with his doctor. The pressure is relentless and we can feel it in so many ways. We see it when Nijinsky stands on a chair shouting out counts, as history tells us he did when his dancers struggled with Stravinsky’s music for Rite of Spring. We see it in the figure of Petrouchka (Lloyd Riggins), pale, wan and squashed emotionally as the drama continues around him. There is a remarkable performance from Aleix Martinez as Stanislaw, the brother, who dies as figures in military dress throw themselves about the stage. And how horrifying are those raucous moments when the dancers, still dressed as figures at war, humiliate Nijinsky as he struggles to cope with his world.

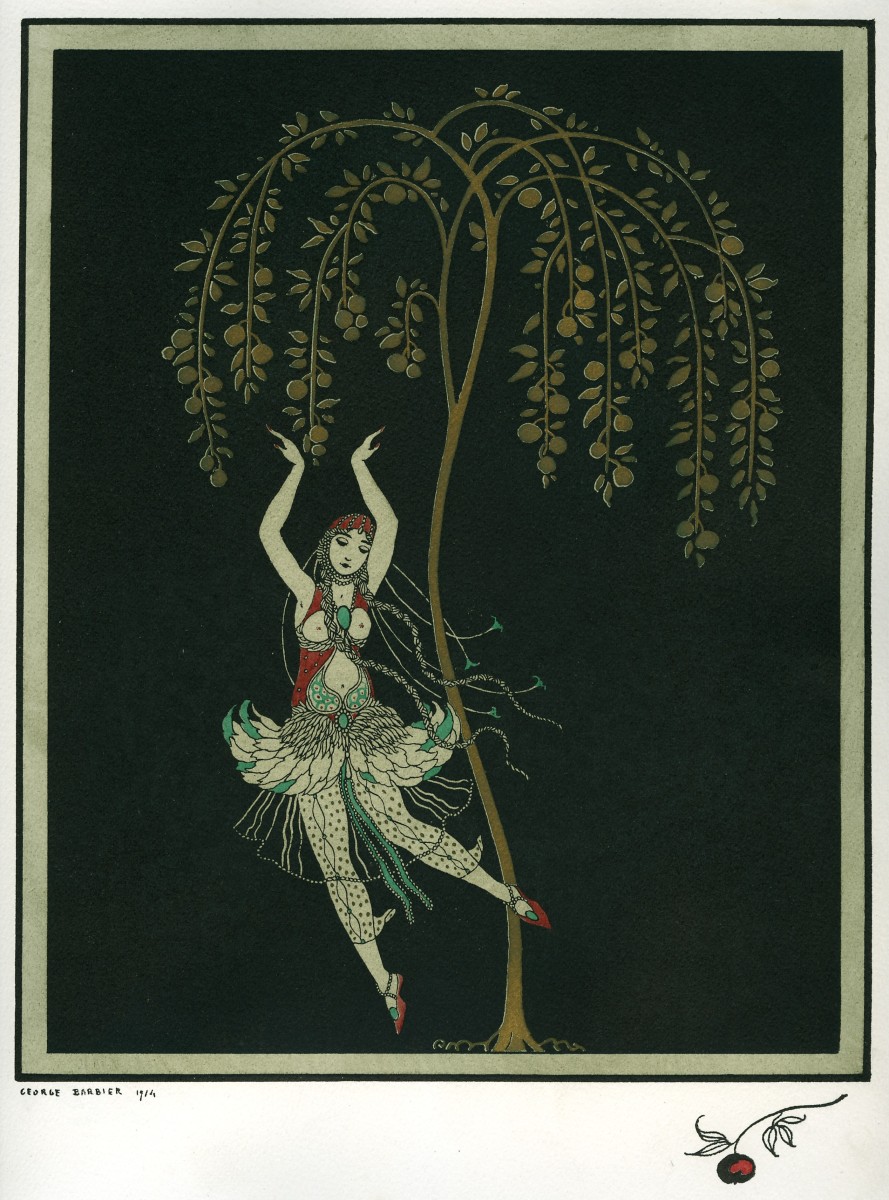

I wonder, however, how easy it was for the audience to understand on occasions who was who and what was happening. It does make a difference to one’s perception of the overall work to know something of Nijinsky’s choreography, and that of his sister Bronislava. There were many times when poses (albeit very well-known poses), from Jeux and Les noces for example, set the work in a particular context. Similarly costumes and props often gave significant clues. Nijinsky is clearly one of those ‘giving’ works that means more each time one sees it; but then not everyone has those opportunities. Neumeier knows his subject well and in fact has a large personal collection of Nijinsky memorabilia and other documentation.** But does he expect the audience to have the same in depth knowledge? Does it matter that not everyone has the same understanding of Nijinsky’s world?

Nijinsky had the audience on its feet at the end of its first performance in Brisbane. It is rare, I believe, for an Australian audience to rise as one and give a standing ovation and I can remember only one other occasion in Australia when I have thought that I was witnessing, and was part of, a ‘real’ standing ovation rather than one that’s a bit like a reverse fall of dominoes—if you want to see the curtain calls you have to stand up because the person in front is blocking your view. Nijinsky is sometimes hard to follow. I was confused at times and it wasn’t my first viewing.*** But the quality of the production, especially its visual strength, some fine performances, and the absolutely compelling manner in which the work surges forward and then concludes by returning to its beginnings in the Hotel Suvretta, generates in the audience an equally compelling desire to stand up and cheer. I did.

Michelle Potter, 28 August 2012

NOTES

*Ramsay Burt has an interesting essay ‘Alone into the world: reflections on solos from 1919 by Vaslav Nijinsky and Mary Wigman’ in the recent publication On stage alone, which I reviewed earlier this month. Burt looks, amongst other things, at the Suvretta performance in the context of Nijinsky’s philosophical opposition to war.

**John Neumeier has an extended essay on his collection and his fascination with Nijinsky in the catalogue that accompanied the major exhibition Nijinsky (1889–1950) at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris in 2000–2001. The catalogue also contains images and information about many of the Nijinsky items owned by Neumeier. See Martine Kahane, Nijinsky 1889–1950 (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000).

***Nijinsky had its premiere in Hamburg in 2000. I was lucky enough to catch it in 2002 when Hamburg Ballet was guesting in Paris. Looking back at that 2002 program it was interesting to see that some roles were, in 2012, still being danced by those who performed them in 2002.