The Australian Ballet’s 2021 season will include performances of George Balanchine’s work, The Four Temperaments, a ballet that had its world premiere in 1946. Then it was performed by Ballet Society, the forerunner to New York City Ballet, in the auditorium of the Central High School of Needle Trades in Manhattan (now the High School of Fashion Industries). For an explanation of the title of the ballet see this link from the George Balanchine Trust website.

Researching the ballet, ahead of its (hopefully live) performances in 2021, has uncovered some fascinating stories, articles and recollections by those who have danced in it over the years, and about the company that first performed it, Ballet Society. According to Bernard Taper in Balanchine. A Biography, Ballet Society was ‘a most peculiar venture’ that was organised by Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein to encourage the production of new works. It was to be an organisation that ‘would cater only to an elite subscription audience’. The press was not invited to the first production, which consisted of The Four Temperaments and Maurice Ravel’s The Spellbound Child (L’enfant et les sortilèges) as staged by Balanchine with an English translation of a text from Colette. The press, however, managed to get to see the show by ‘buying their own subscriptions’ or ‘sneaking into the auditorium on performance nights’. So began a ballet that was ground breaking then and is still remarkable today. It is more often than not described as ‘A dance ballet without plot’ (Balanchine’s subtitle), but according to Taper ‘[it] seemed to demonstrate that ballet could do anything that modern dance could do—and more.’

It was not (and is not) an easy ballet to dance. In the beginning there were the costumes to contend with. The original costumes were designed by Swiss-American artist Kurt Seligmann and were somewhat extravagant and not easy to wear. In Barbara Newman’s Striking a balance, Tanaquil LeClercq, who danced in the corps de ballet in the original production, recalls:

I had a large nylon wig that came down to about my rear end. It had a large pompadour, and it had a large white horn in the middle like a unicorn’s, which made it difficult to do all the things [Balanchine] had made. That was number one. Very irritating. You come to dress rehearsal, and if you swing your arm close to your head, suddenly there’s a horn. The other thing was that [Kurt] Seligmann had made wings, red wings, fingers enclosed, and there was no place to get out. If you got into your costume and then got something in your eye or wanted to unzip yourself to get out, you couldn’t. Once you tied your toeshoe ribbons, that was it. It gave you a feeling of claustrophobia I can’t describe. All enclosed. Not even gloves with fingers—no fingers at all. It was hideous.

The Seligmann costumes were eventually abandoned and were replaced from 1951 by simple practice clothes, black leotards for the women, and black tights and a white T-shirt for the men, which are still worn today.

Then there was the choreography. Merrill Ashley, in her memoir Dancing for Balanchine, speaks of some of the choreography she found difficult. She danced the leading role in the Sanguinic section when the work was revived for New York City Ballet after slipping out of the repertoire for some years. She writes:

There was one movement about which [Balanchine] was particularly concerned. He wanted me to step backward on pointe and then, without traveling at all, put my heel down flat on the floor and let my body fall back—without losing control. Actually the step was meant to make me look as if I had fallen off pointe suddenly, and was therefore falling back. It was very difficult, especially lowering the foot without moving the heel at all. I wasn’t able to do it right, but when Balanchine told me that no one else had ever done it correctly either, I felt a little better. Although I come closer to it now, I still move my foot as I lower my heel.

Quite recently the NYCB website published an article by NYCB’s Manager, Editorial and Social Media, Madelyn Sutton. It is well worth a read and it also contains two video snippets. Read and watch at this link.

In Australia, The Four Temperaments premiered in 1985 when the Australian Ballet was under the directorship of Maina Gielgud. The ballet was staged by Victoria Simon and appeared on a program with Balanchine’s Serenade and the first performance of Robert Ray’s The Sentimental Bloke. (It is perhaps of interest to note that in 2021 The Four Temperaments will be part of a similarly constructed program, which will also include Serenade and the first performance of a newly commissioned work from New York-based choreographer Pam Tanowitz). Later, in 2003, Australian audiences saw it on an Australian Ballet program called American Masters, which also included Glen Tetley’s Voluntaries and Jerome Robbins’ In the Night. Again it was staged by Victoria Simon. It was brought to Australia by New York City Ballet in 1997 when that company toured to the Melbourne Festival, and was last performed here by the Australian Ballet in 2013 as part of its Vanguard season. Then it was staged by Eve Lawson. I am curious to know who will stage it in 2021.

Michelle Potter, 13 January 2021

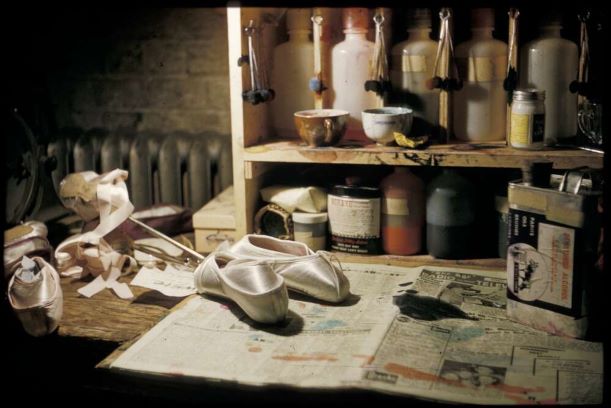

Featured image: Backstage at Her Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne, during the 1958 tour to Australia by New York City Ballet, 1958. Photo: Walter Stringer, National Library of Australia.

(The Four Temperaments was not performed during this 1958 tour. I just like the image and my use of it reflects difficulties associated with permission to use images of The Four Temperaments. The article by Madelyn Sutton mentioned above contains some very nice images.)

Bibliography

- Ashley, Merrill. Dancing for Balanchine (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1984)

- Balanchine, Georg, and Francis Mason. Balanchine’s Festival of Ballet (New York: W. H Allen & Co, 1984)

- Newman, Barbara. Striking a balance. Dancers talk about dancing. Revised edition (New York: Limelight Editions, 1982)

- Taper, Bernard. Balanchine. A Biography (New York: Times Books, 1984)