Early in July I gave a brief presentation in Melbourne at the Cecchetti Ballet conference for 2018. The conference included a session relating to Marie Rambert and the tour made by Ballet Rambert to Australia and New Zealand between 1947 and 1949. Other speakers for this session were Jonathan Taylor, Audrey Nicholls and Maggie Lorraine who spoke about their experiences with the company after the Australasian tour. As we each had just 10 minutes each my introductory talk was necessarily brief. Nevertheless, I am posting it here.

************************************************************************

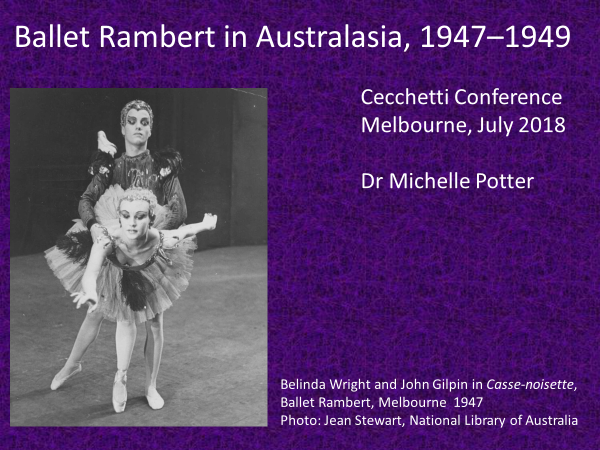

Ballet Rambert, led by the irrepressible Marie Rambert, came to Australia in 1947 for a tour that lasted until January 1949. On this slide you can see two of the dancers who made a particular impact in Australia, Belinda Wright and John Gilpin, both very young at this stage in their careers. In many respects the Rambert tour has been somewhat neglected compared with the attention that has been given to the Ballets Russes companies whose tours to Australia took place largely in the mid to late 1930s and in 1940. Today I only have 10 minutes to talk to you about the Rambert tour, which I delved into while writing my biography of Dame Margaret Scott. Maggie, as you most likely know, first came to Australia with the Rambert company and then made her subsequent career in Australia.

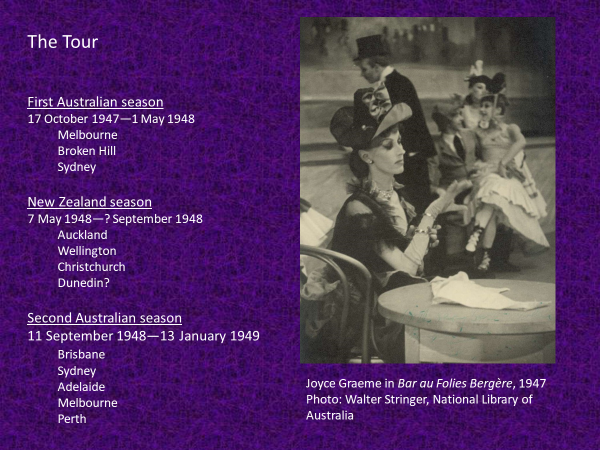

On this slide I have listed the towns and cities visited by the company. Unfortunately, the information for the New Zealand leg of the tour is not complete. I didn’t investigate that side of the company’s activities in great detail because Maggie Scott didn’t go to New Zealand. She was lying in bed in a plaster cast in St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney. So, the New Zealand leg of the tour needs a bit more research.

Perhaps the most surprising part of the tour is a visit to Broken Hill, a three-night stand made in January 1948. It was made possible by sponsorship from several mining companies in the area. A local newspaper, Barrier Daily Truth, reported that Marie Rambert had introduced each ballet. ‘She was almost a star turn in herself, for she made no weary speeches but tickled the audience’s fancy by her humorous and witty remarks and explanations of the ballets’. But I’m sure it was a somewhat remarkable experience for the dancers to go to Broken Hill. This is what Broken Hill looked like then in a photo, sadly badly faded, from the private collection of one of the dancers.

And the weather was enervating. It was well over 100⁰ Fahrenheit in the shade each day and the dancers were sometimes performing in costumes that were heavy and very hot to wear. Those for The Fugitive for example were made of heavy English felt. But Cecil Bates, an Australian member of the company, recalls that they were well looked after. ‘The local people kept a running chain of iced orange juice in huge metal ice cream containers. They just kept a continuous line of it and as we came off stage we would have a glass of icy cold juice and then go back on. We would have passed out otherwise’.

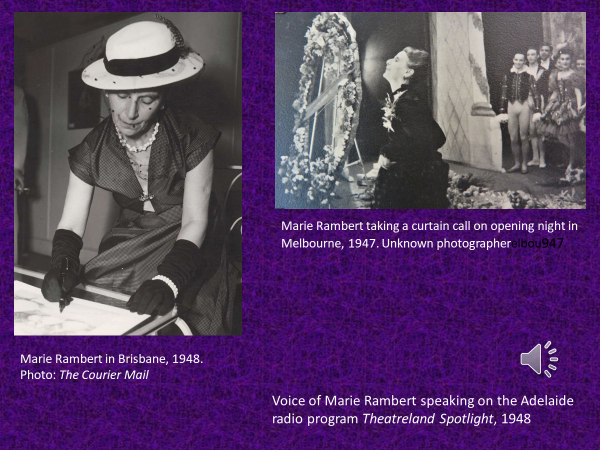

But the tour was extensive and, on this slide, I give you Mme Rambert herself.

You see her on the left in Brisbane in 1948 looking very smart as she signs some document or other, while on the right you see her accepting applause for the opening night performance, the first performance in Australia in Melbourne. I know that other speakers will have more to say about Mme Rambert so I will simply let you heart her voice. She is speaking from Adelaide in 1948 giving the interviewer her thoughts on the success of the tour. And you’ll hear Ron Sullivan, the interviewer, attempting to get a word in every so often….but failing! Voice of Marie Rambert.

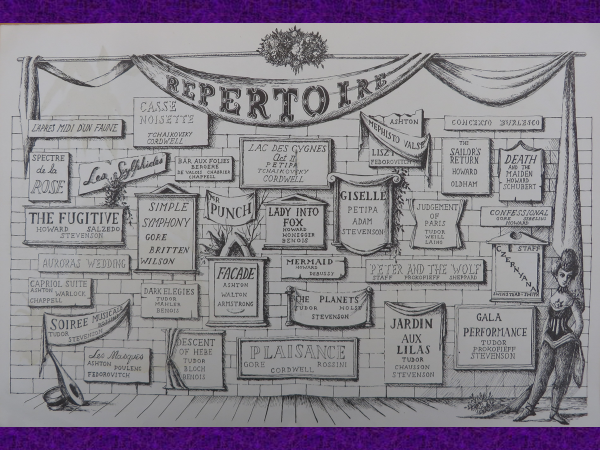

Not only was the tour extensive in terms of cities visited and time spent in Australia, the repertoire was also interesting.

This page from the souvenir program gives you an idea of the variety of fare that Australian audiences saw. There were classics of course but also works from English choreographers who were in the early stages of their careers—Frederick Ashton and Antony Tudor, for example—as well as female choreographers such as Andrée Howard and Ninette de Valois, as well as others from within the company including Walter Gore and Frank Staff.

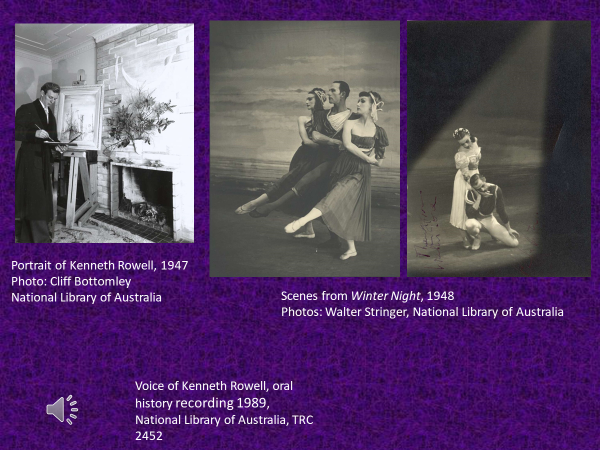

And I’d like to play you some comments about the tour by Australian designer Kenneth Rowell. Rowell was an emerging designer at the time and for him major commissions were few and far between in Australia. He was offered the commission to design Winter Night, a ballet by Walter Gore, which was the only work created in Australia by the Rambert company. Voice of Kenneth Rowell

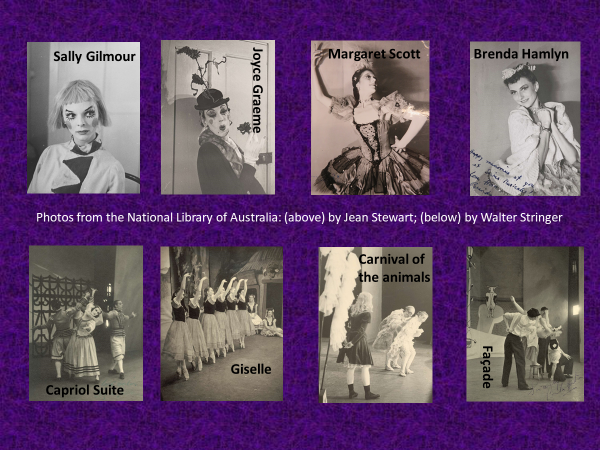

And on the next slide I have some photos taken by two Australian photographers who did much to document the tour: Jean Stewart with some portraits of dancers, and Walter Stringer with a variety of performance shots.In the top row you see Sally Gilmour in Peter and the Wolf, Joyce Graeme in Peter and the Wolf, Margaret Scott in Gala performance, and Brenda Hamlyn in Soirée musicale.

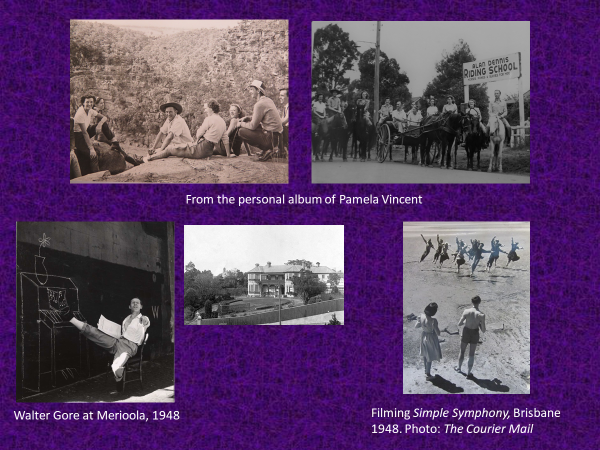

One aspect of the tours that I found quite fascinating was the extra-curricular activities of the dancers and support staff. It was quite well known that, while in Australia, the Ballets Russes dancers engaged in all manner of socialising with visits to koala sanctuaries, swimming parties, dinners given by fans and sponsors and so on. But so did the Rambert dancers. And in this next slide are two images from the personal scrapbook and album of Pamela Vincent, a Rambert dancer who incidentally married an Australian musician, Douglas Whittaker. I was lucky enough to have access to Pamela Vincent’s material at the Rambert Archives in London. So, the Rambert dancers also had good times on their days off.

And when in Sydney, the dancers frequented a bohemian establishment called Merioola, home to artists, photographers, poets, and writers. Here you see Walter Gore at Merioola and the big house itself (now demolished) which was in Woollahra. And if you think back to the repertoire list I showed earlier, that page and much of the souvenir booklet was designed by Loudon Sainthill who was part of the Merioola group,

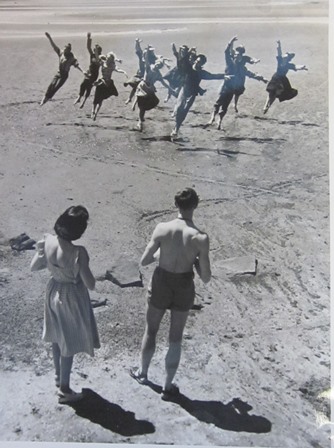

Another extra-curricular activity that is quite interesting relates to the ballet Simple Symphony, which was created in England by Walter Gore during World War II when on leave from duty in France with the armed forces and which was created largely on Sally Gilmour and Margaret Scott. It premiered in Bristol, England, in November 1944 and was performed throughout the Rambert Australasian tour. A note in Rambert Australian programs says it was ‘a thank-offering created by Walter Gore … a few months after he was twice torpedoed on D-Day’. It was also filmed during the Australian tour at Sandgate, a beachside suburb north of Brisbane. It was anticipated that the film would be distributed to schools in Queensland, although I am not sure whether this ever happened. The photo you see was taken on location during the filming in September 1948 and a copy of the film is now in the National Film and Sound Archive.

So, thank you. There is so much more to say, listen to and watch of course but I hope this has given you a glimpse of the Ballet Rambert tour. Should you be interested in more, you may like to read my biography of Dame Margaret Scott, which is still available through the website of Text Publishing here in Melbourne. Thank you.

************************************************************************

Follow this link for information on how to order Dame Maggie Scott’. A life in dance via the Text website.

Here is a taster of what Maggie and her friend Sally Gilmour experienced on their first day in inner city Melbourne: ‘The first day we woke up I heard this noise, a commotion outside. You really wouldn’t believe it but there were some sheep dogs rounding up a flock of sheep outside the hotel—getting them out of the doorways, running along their backs. It was really quite extraordinary.’

See also an article published in December 2002 by the National Library in their monthly magazine (now defunct unfortunately) National Library of Australia News. Here is a link to that article.

Michelle Potter, 24 July 2018

Featured image: Ballet Rambert in Australia, c. 1948. Collection of Pamela Vincent. Marie Rambert in the sulky perhaps?