- Kristian Fredrikson. Designer

My book, Kristian Fredrikson. Designer, is now available in bookshops across Australia, and from online outlets, including the publisher’s site, Melbourne Books, and specialist online sellers such as Booktopia and Book Depository. I am indebted to those generous people and organisations who contributed to the crowd funding projects I initiated to help with the acquisition of hi-res images, where purchase was necessary, and to other photographers and curators who contributed their work and collection material without charge. I am more than happy with the reproduction quality of the images throughout the book.

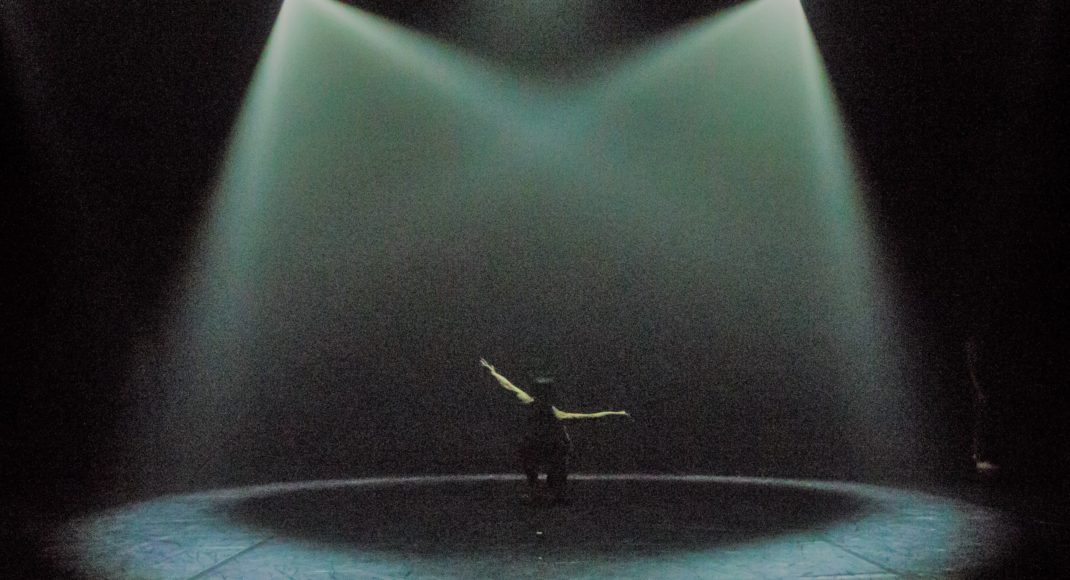

The featured image on this post is from a New Zealand production of Swan Lake and, in addition to Fredrikson’s work in Australia, his activities in New Zealand are an integral part of the book. So too is his work for Stanton Welch and Houston Ballet, and reflections from Houston Ballet staff on the Fredrikson-designed Pecos and Swan Lake also are integral to the story. The book features some spectacular images from those two works.

Two promotional pieces for the book are at the following links: Dance Australia; Canberra CityNews.

- Royal Danish Ballet

It is a while since I saw a performance by the Royal Danish Ballet so I am looking forward to watching the company dance via a stream from Jacob’s Pillow taken from a performance they gave there in 2018. More later… In the meantime, read my thoughts on the 2005 Bournonville Festival in Copenhagen. I was there on behalf of ballet.co (now Dancetabs).

- Further on streaming

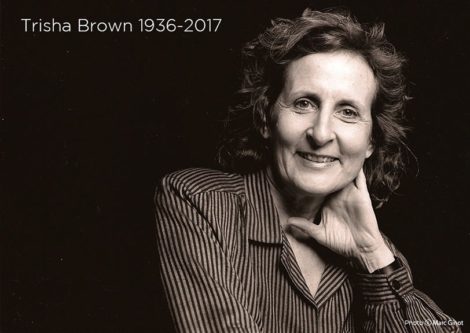

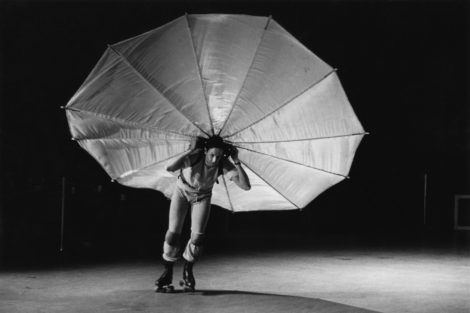

Two productions, which streamed in July, which I watched but haven’t reviewed in detail, were Trisha Brown’s Opal Loop/Cloud Installation and Aszure Barton’s Over/Come. Both were streamed via the Baryshnikov Arts Centre site. I was especially interested in Opal Loop/Cloud Installation because the installation, which provided the visual background for the work, was by Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya. Nakaya is renown in Canberra for his fog installation (Foggy wake in a desert: an ecosphere) in the sculpture garden of the National Gallery. My grandchildren love it, some for the way the fog comes from the ground-level structure that generates it, others simply for the presence of the fog! I wondered what it was like to dance amid the cloud/fog in Opal Loop.

But I love watching the loose-limbed dancing that characterises Brown’s choreography and have great memories of watching various of her pieces performed, several years ago now, at the Tate Modern.

As for Aszure Barton, Over/Come was created while Barton was in residence at the Baryshnikov Arts Centre, and was filmed in 2005. Efforts to find out a bit more about it, especially the dancers’ names, have been pretty much unsuccessful. Two dancers stood out—a tall gentleman wearing white pants that reached just below the knee (his fluidty of movement was exceptional), and a young lady who danced a cha-cha section. I’d love to know who they are.

- The Australian Ballet

How devastating that the Australian Ballet has had to cancel its Sydney season for November-December, meaning that very few performances from the company have made it to the stage in 2020. I guess I was lucky that I managed to get to Brisbane in February to see The Happy Prince. 2020 is not the kind of farewell year David McAllister would have liked I’m sure.

Michelle Potter, 31 July 2020

Featured image: Abigail Boyle and Jon Trimmer in Russell Kerr’s Swan Lake. Royal New Zealand Ballet, revival of 2007. Photo: © Maarten Holl /RNZB. Courtesy of Matthew Lawrence