10–20 April, 2024. Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London

reviewed by Sonia York-Pryce

It has been 10 years since the inaugural Elixir Festival, the brainchild of Chief Executive & Artistic Director of Sadler’s Wells, Alistair Spalding, and Artistic Programmer and Producer of the Elixir Festival, Jane Hackett. Created in 2014 as ‘a celebration of creative ageing’, the 4-day festival thrust the subjectivity of dance and ageing into the spotlight, highlighting the artistry of older professional dance artists. It featured works by Mats Ek, Pascal Merighi, Hofesh Shechter, Matteo Fargion and Jonathan Burrows with performances by Dominique Mercy of the Pina Bausch Company, Mats Ek with his muse Ana Laguna and Argentina’s Generación Del Ayer, plus former members of London Contemporary Dance Theatre returning to the stage. This program drew a full house confirming that audiences were interested in seeing diversity, with great artists performing irrespective of their age. The Company of Elders, Sadler’s Wells longstanding community dance company, performed alongside other amateur companies from the UK. The Art of Age conference brought together dance scholars, and educators to discuss the continuing age bias and the need for more inclusivity within the field of Western dance.

Move on a decade and the Elixir Festival 2024 has grown in stature and prominence. The festival has been co-funded by the Creative Europe Program of the European Union, as part of DANCE ON, PASS ON, DREAM ON. Spanning over eleven days, featuring performances from international professional dance artists from 12 countries, amateur dancers, workshops, Elixir on digital stage and talks. Dance featuring seasoned performers is certainly becoming more mainstream, but progress is still needed to maintain a permanent presence. Headliners included the Mother of African dance Germaine Acogny, performing alongside, Malou Airaudo from Pina Bausch Company, Louise Lecavalier, Charlotta Öfverholm, Dance On Ensemble Berlin, Ben Duke and Christopher Matthews to name but a few, accompanied by Sadler’s Wells Company of Elders, with UK based amateur performance groups.

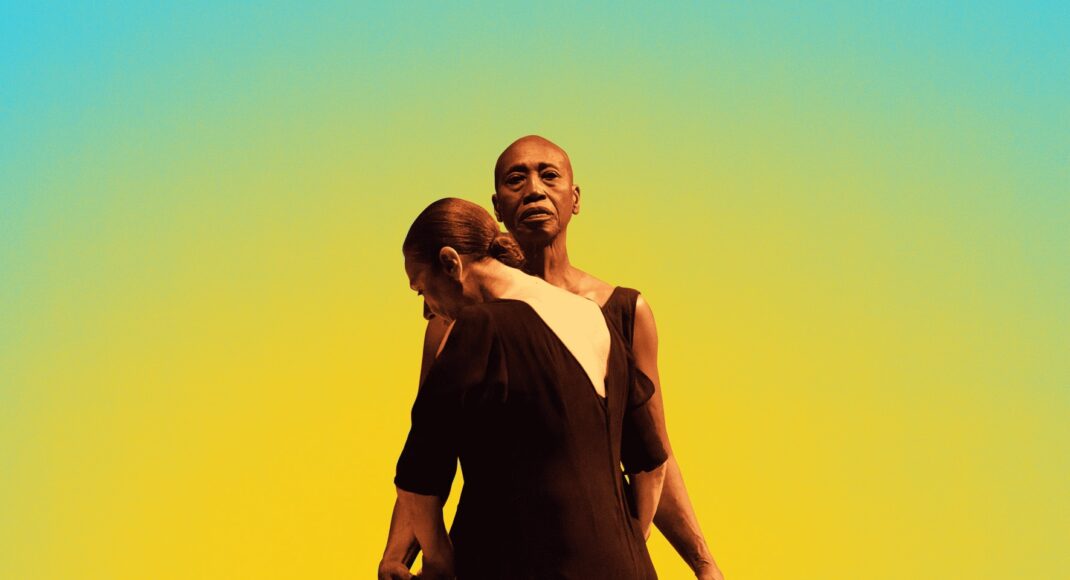

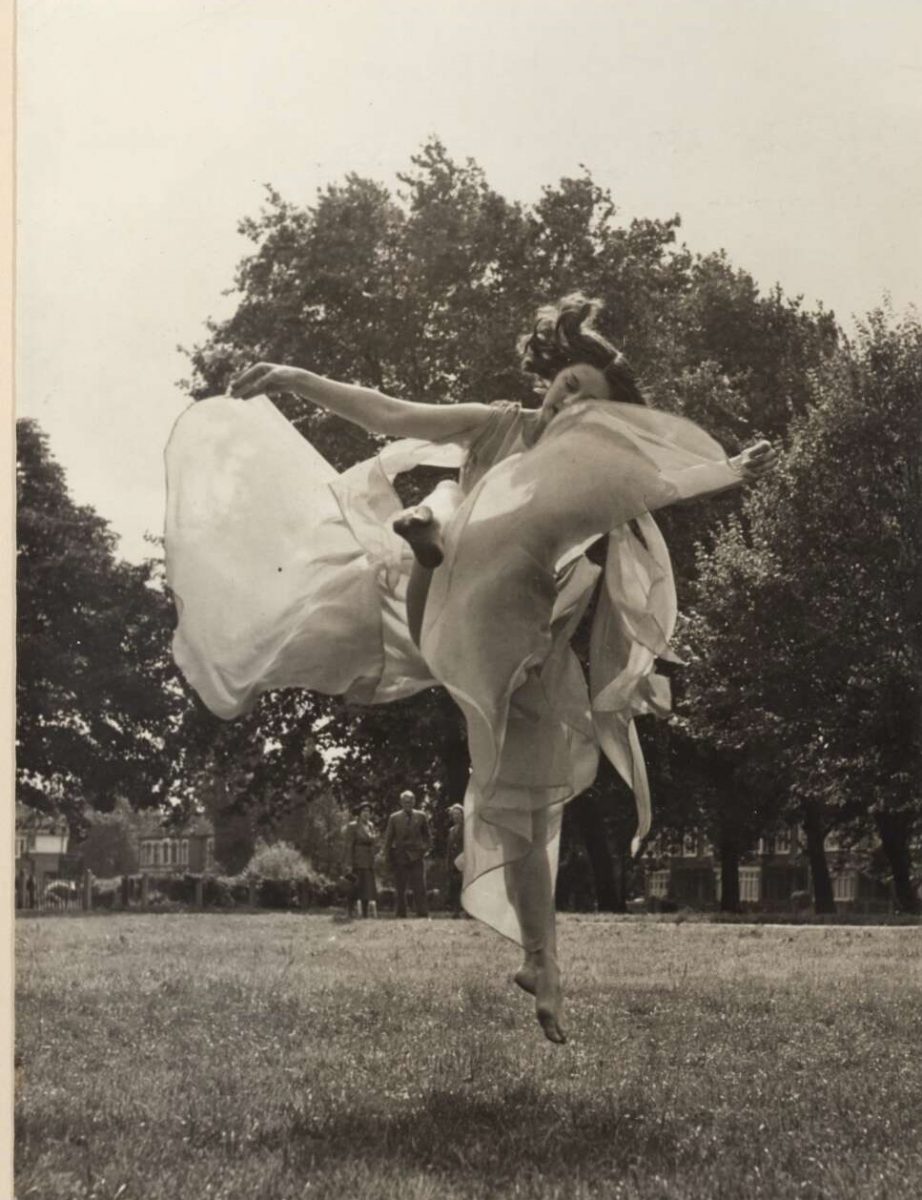

The opening night’s triple bill was a feast of creative ageing and life experience. Germaine Acogny (79) founder of Senegal’s École des Sables and Malou Airaudo, who incidentally was celebrating her 76th birthday on the night, performed their first work together, Common Ground[s] to Fabrice Bouillon LaForest’s accompaniment on strings. Beautifully lit by Zeynep Kepekli to highlight the two acclaimed performers, with costume design by Petra Leidner, it is a work that shows them in a variety of modes, as warriors and survivors of dance. Whilst giving each other respect, there is tenderness, and a mirroring of motion. The audience were delightfully receptive to these two dance elders, and it certainly made a strong statement that seeing ‘age on stage’ was receiving the respect it warranted. This work has toured internationally as a worthy partner alongside Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring. Bausch was an early advocate for intergenerational dance, valuing the assets ageing brought to the performance.

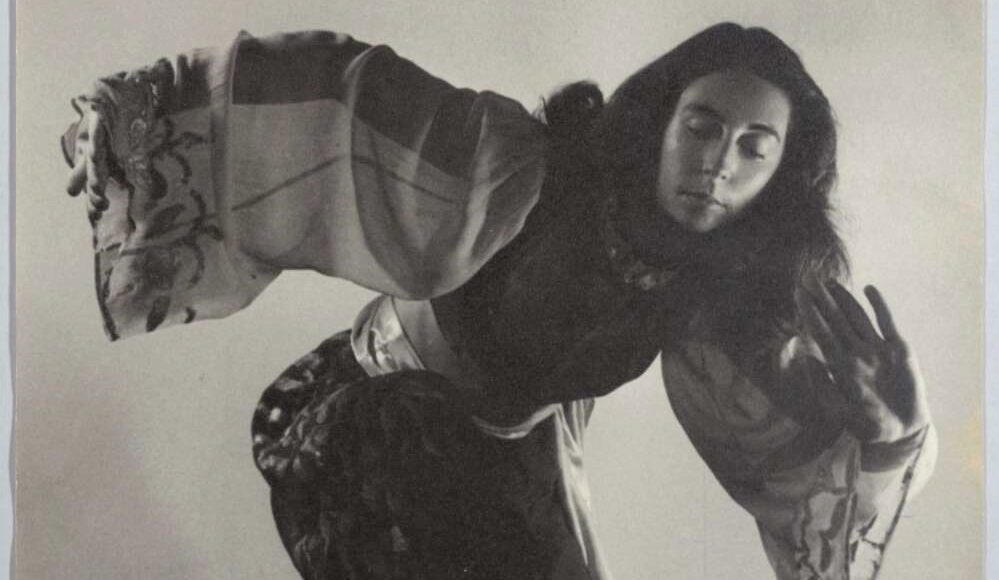

To follow Louise Lecavalier (65), the punk princess of contemporary dance, famed for her incredible gravity defying performances with Edouard Lock’s La La La Human Steps in the 1980s, performed her work, Minutes around late Afternoon. She has come to choreographing late in life but through this work she continues to thrill with her ceaseless moving, arms in constant motion, mirrored by those feet as she bourrées endlessly, gliding across the stage, effortlessly. Dressed in black by designers Yso & Elizabeth Duran, she is defined by the starkness of the stage lighting by Alain Lortie and François Blouin, with her face at times obscured by her blonde tousled hair cascading out of a hoodie. She could be a teenager, judging by her unlimited stamina and presence as she moves continuously, with hardly a breath exhaled as she balances ceaseless motion with the accompanying sound mixing of Benot Beaupre. Music by Antoine Berthiaume (Lien 3), The black dog (Bass mantra, Greddy gutter guru), Dawn of midi (Atlas), are laudable partners to her performance. Lecavalier gives a masterclass in ‘seeing is believing’, defying all concepts that you are too old to thrill. She is just as exhilarating to watch now as she was when a ‘no limits barred’ dancer back in the 80’s. May she never stop!

The final work for the evening White Hare, was commissioned by Sadler’s Wells, and is described as a trio for 2 dancers and a tortoise. Choreographed by artistic director Ben Duke of LOST DOG with fantastic performances by 50 somethings Christopher Akrill and Valentina Formenti as a middle-aged couple navigating life. Duke is known for producing work with a dark satirical edge and this is no different as it traverses life in reverse with issues of Armageddon, survival, and trivialities of life. This alongside the aptly named Tipple the tortoise, who perhaps appears as a metaphor for longevity. It’s a beautiful, humorous piece with exuberant dancing from both, with the set design by Delia Peel and sound by Jethro Cooke. It is a fitting foil to end the evening’s wonderful inspirational performances.

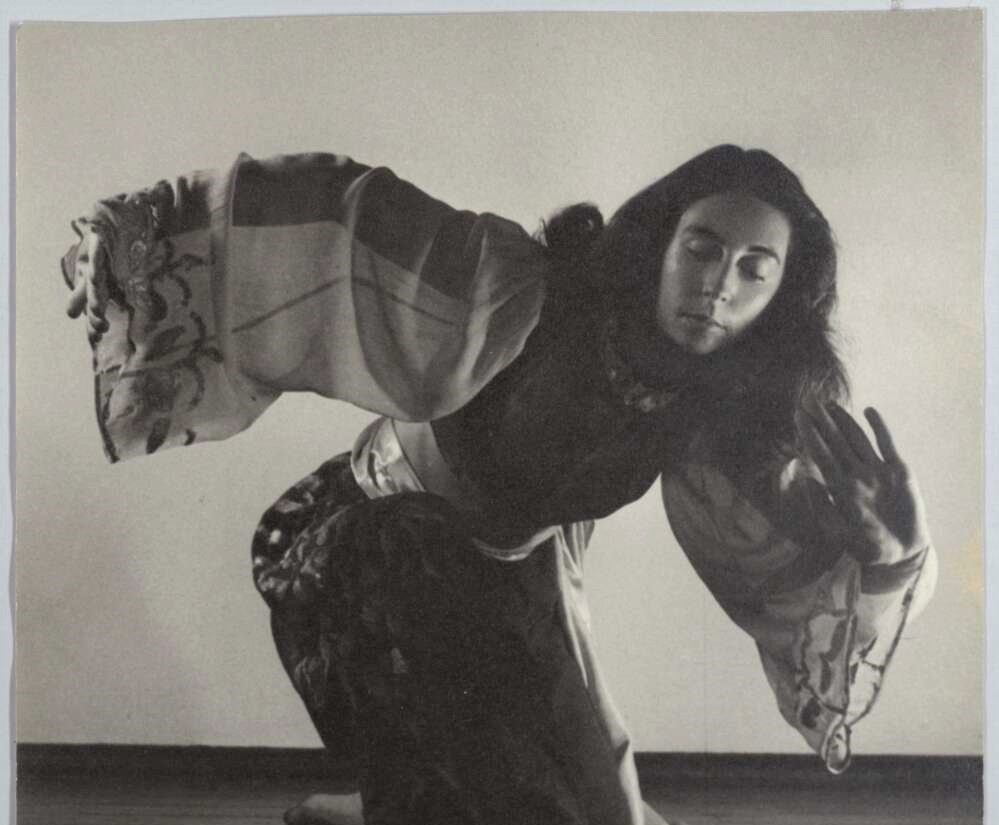

Throughout the festival choreographer, performer and visual artist Christopher Matthews/FORMED VIEW premieres ACT 3, the final work of his trilogy, following on from My Body and Lads. Here Matthews explores queer masculinity, obscured emotions, identity, fragility, intimacy, ageism and the male gaze in later life. In an artist talk during the festival with Nicola Conibere he revealed how he needs to re-think dance history, questioning how masculinity is defined in dance. For ACT 3 he references Kenneth MacMillan’s bedroom scene from Romeo & Juliet, imagery from New York based photography collective PaJaMa, queer writers of the 1930s and 40s with further inspiration from the nude male Greek and Roman marble sculptures in Munich’s Glyptotek. The work features a cast of male collaborators all over the age of 60, Donald Hutera, Bruce Corrie, Andy Newman, Roberto Ishii, John Charles Marshall, Markus Trunk and Stephen Rowe. This is a statement in itself, as male performers of this age are rare to see performing. So, giving them a place to perform and be seen is a triumph. The set is minimal, a mattress covered in white fabric, the men similarly costumed, and the observed starkness brings for greater visibility of the content. By using the domestic setting of a bedroom, he experiments with intimacy by bending the boundaries of realism and fantasy. The work is improvised with butoh-inspired movements that explore tenderness and connection. Matthews is interested in what is considered high or low art and interrogating how an audience observes performance. The work was first shown on the opening night of the festival in the upstairs foyer of the main theatre then later in a similar space in the Lilian Baylis Studio. It was well received.

On April 12th the double bill brought together Charlotta Öfverholm and Jordi Cortés former members of DV8, In A Cage of Light and Susan Kempster’s Mother in the Lilian Baylis Studio. Öfverholm and Cortés, choreographed and performed the work alongside fellow collaborator Tobias Hallgren, with the score played by composer and musician Lauri Antila. Öfverholm and Cortés bring together a sublime physical theatre performance of wit, balance, showmanship, humour, melancholy, drama, authenticity and life experience. These seasoned performers are so comfortable on the stage. Not for one minute is there any respite for Öfverholm, as she is either swinging on a trapeze high above the stage ready to plummet or hanging by her fingertips from a ridiculously high steel bar fixed perilously high on the wall stage right, or metaphorically assuming the role of a cello artfully played by Cortés. These performers accomplish what we believe is impossible for older dancers let alone older people to achieve. The piece moves at a rapid pace and concentration is essential to keep a breadth of their performance through dance, voice, song or stillness. This is a well performed piece and timing is of the essence. Their love for performing is all encompassing and the audience love the ride.

Kempster’s Mother commissioned by Sadler’s Wells, featured an intergenerational duet which looked at intimacy, ageing and how this is perceived when we look at the relationship between an older woman and a young man or perhaps a mother and son. It is a work that looks at two different bodies, ambiguity and assumptions, contemporary dance partnering, with the connections and perceptions that inspire Kempster. Danced by creative collaborators Charlotte Broom and Harry Wilson, the work is bursting with free-flowing movements filling all angles of the stage with score by composer Dirk Haubrich. The dancers are costumed similarly in stunning bronze fabrics designed by Jessica Cabassa which enhance the movements of the dancers, with lighting design by Ros Chase. To follow on from the physical theatre of Öfverholm and Cortés was a hard task, with the lines of distinction at times blurred, but it was the pure dance that triumphed, and it appeared the dancers enjoyed the experience as much as the audience.

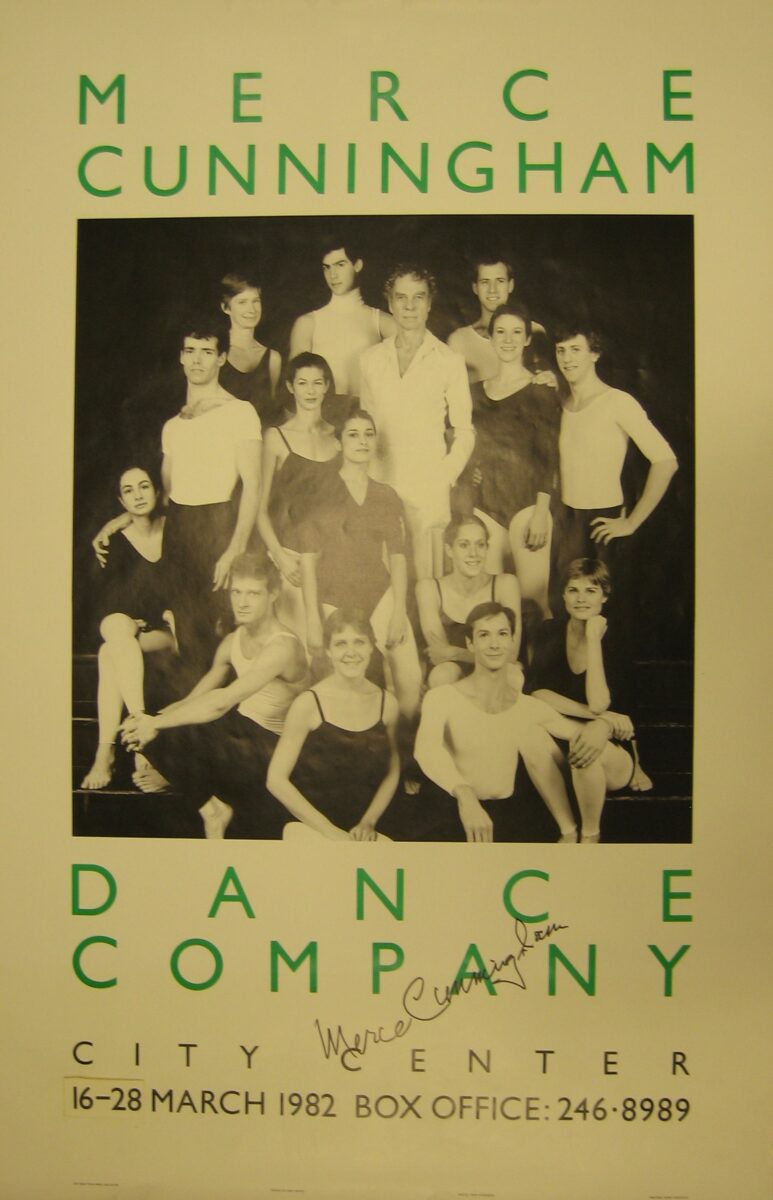

On April 17th in the Lilian Baylis Studio, Berlin’s Dance On Ensemble brought 2 works, London Story a reimagining of Merce Cunningham’s (1963) Story and Mathilde Monnier’s reworking of the former to produce Never Ending (Story). Dance On Ensemble is the first mature dancer company founded since the legendary NDT3, (1991-2006) and is on its second iteration with continued secured funding from the German Federal Government. They also form part of DANCE ON, PASS ON, DREAM ON. Sadler’s Wells is also one of 11 DOPODO partners co-funded by the European Union. Incidentally for Sadler’s Wells that partnership will come to an end after Elixir 2024, which is a great loss for the establishment and UK dance in general. Story featured dancers, Ty Boomershine, Tim Persent, Marco Volta, Emma Lewis, Gesine Moog, and Jone San Martin. The original improvised work was performed numerous times with constant changes and alterations allowed at each performance; with only one filmed version in 1964 for reference. So, the archive is indeed limited and much remains unknown other than some notes from Cunningham himself. With this in mind DOE has chosen to re-imagine the work with the assistance from Cunningham re-stager Douglas Squires. Centre stage is set with a huge pile of clothes that the cast rummages through, puts on, takes off and changes numerous times. The scenery consists of 2 black boards with text charting time changes, transitions, performance and movement notes, all are markers for the audience to understand how the performance will progress. Matching this is the score by Toshi Ichiyanagi with live music provided by Mattef Kuhlmey, with a digital clock that sets the pace as it runs simultaneously throughout the performance, clocking the clothing changes, transitions, changes of direction and much more. This version is colourful, joyful, amusing and certainly retains its modernity. The re-imagined choreography gave the cast wonderful opportunities to highlight their capabilities and they work beautifully as an ensemble. With lighting designs by Martin Beeretz, costumes by Sophia Piepenbrock-Saitz and visual artist Christopher Matthews assumes the role of Cunningham collaborator Robert Rauschenberg, providing ready-made stick images in primal coloured tape depicting dance moves offering further embellishment and humour to the work.

Mathilde Monnier’s Never Ending (Story) is her response to Cunningham’s Story using the poetry of David Antin (1932-2016), a contemporary of Cunningham and John Cage. Monnier experiments with how thought and movement come together. This work is the antithesis of Story in that it is a structured composition with the dancers constantly on the move. The contrast between Antin’s poetry and Monnier’s choreography frequently produces moments of real humour. The cast of Ty Boomershine, Marco Volta, Gesine Moog, Emma Lewis, and Jone San Martin, bring together, voice, movement, thought and repetitions in an altogether entertaining piece. Light design is by Martin Beeretz, costumes by Mathilde Monnier and sound design by Mattef Kuhlmey.

These two works illuminate the skills of Dance On Ensemble and demonstrate that artistry is at the forefront here. How fortunate the audience is to see this company demonstrate that dance need not have an expiry-date, but that age and life experience become assets that embellish and imbue a performance.

Sonia York-Pryce, 20 June 2024

Featured image: Elixir Banner, featuring Germaine Acogny and Mailou Airoudo. Image credit: Sadler’s Wells