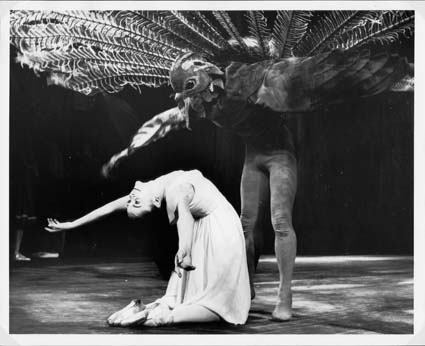

Barry Kitcher, who has died in Melbourne aged 89, is probably best known for his role as the Male (the Lyrebird) in Robert Helpmann’s 1964 ballet The Display. In an oral history interview recorded for the National Library of Australia in 1994* he recalled what he saw as the highlight of his career—taking a solo curtain call at Covent Garden when the Australian Ballet staged The Display there during its international tour in 1965.

A highlight of my career was taking a curtain call on that incredible stage where the butterfly curtain goes up. There were the two lackeys at Covent Garden, in powdered wigs. They parted the curtain and I took a solo curtain call. Never did I think as a country kid from Victoria that one day I would be taking a curtain call at Covent Garden. Princess Margaret came to the performance and she told me how much she enjoyed the performance. She was fascinated by the mechanism [of the costume] and asked me if I could open the tail, which I did.

But Kitcher had an extensive career in Australia and overseas, which encompassed so much more than his performances in The Display, despite the fame that that one role gave him. His introduction to ballet came when, in 1947, aged 17, he saw a performance in Melbourne by the visiting English company, Ballet Rambert. He was inspired, as a result, to take classes with Melbourne teacher Dorothy Gladstone but eventually moved on to study at the Borovansky Academy. There he took evening classes with Xenia Borovansky while working as a clerk with Victorian Railways during the day.

He spoke of his impressions of Xenia Borovansky, again in his National Library oral history interview.

She was very tall, extremely tall—she towered over Boro—and she wore high heel shoes as well. She was so regal and elegant and when she walked into a room it was like a star. She had rather bulbous eyes. You really stopped and looked at Madame Boro as she came in … she was a very impressive lady. Her carriage and her stature were outstanding.

He joined the Borovansky Ballet for the 1950–1951 season when the company reformed after a period in recess. He took on many roles with the Borovansky company over the years, but recalls in particular dancing in Pineapple Poll when it was staged by its choreographer, John Cranko; taking on the role of the Strongman in Le beau Danube after Borovansky’s death; and dancing as one of the three Ivan’s in The Sleeping Princess.

At the end of his first season with the Borovansky Ballet, the company went into recession once more and Kitcher spent time appearing on the Tivoli circuit. He then left Australia in 1956 to try his luck in England, as did so many of his dancing colleagues at the time.

In London he took classes with legendary teacher Anna Northcote and later with Marie Rambert; danced at the London Palladium as a member of the George Carden Dancers, with whom he appeared in a number of shows including Rocking the Town and a Christmas pantomime The Wonderful Lamp; joined Sadler’s Wells Opera Ballet and appeared in the The Merry Widow; and danced with London City Ballet.

He returned to the Borovansky Ballet in 1959 and then went on to dance with the Australian Ballet from its opening season in 1962 until 1966.

After leaving the Australian Ballet he joined Hoyts Theatres and trained as a theatre manager working in various Melbourne-based cinemas. Eventually he successfully applied for a position as theatre manager with the newly opened Victorian Arts Centre where he worked for several years.

But for all his achievements across many areas, Kitcher was probably most proud of being a member of the Borovansky Ballet. He was responsible for many organisational details associated with the various reunions of former Borovansky dancers, which began in 1993, and throughout his oral history interview he spoke constantly of the artists he worked with, including Borovansky himself as well as Xenia. He loved in particular discussing the nature of the company and the closeness he felt there was between those who worked with it.

My favourite quote from his oral history comes from Kitcher’s recollections of time spent touring in New Zealand, which the Borovansky company did frequently. Speaking of the unofficial concerts the company staged amongst themselves, especially one held in Christchurch at the Theatre Royal, he recalled:

To raise money for our big farewell party in New Zealand (we had a wonderful party) we had a big fete onstage during the afternoon at the Theatre Royal in Christchurch. The stagehands and everybody joined in. Boro contributed a fish that he’d caught—he was a great fisherman, loved fishing. That was his relaxation away from the theatre—fishing and painting. All the principal ladies, Kathy [Gorham] and Peggy [Sager], made cakes and things like that. Oh, we had a wonderful time … It was a great company and, as dear Corrie [Lodders] said, ‘It was a company of family’ … We were very, very lucky to be part of that era.

Listen to this quote.

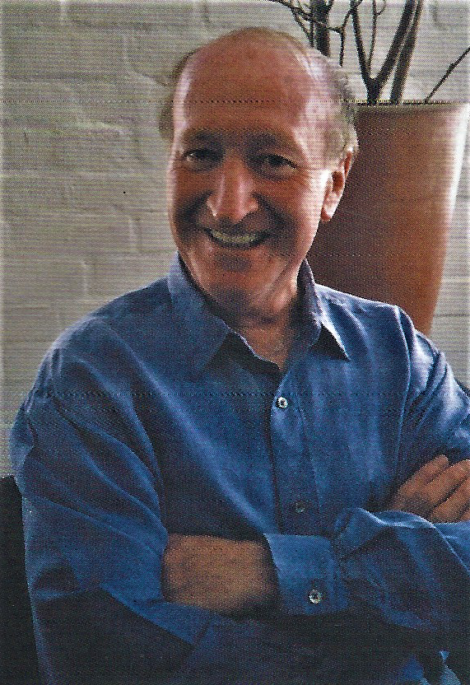

Barry Kitcher was a kind and thoughtful man. He never forgot me as his interviewer for the National Library’s oral history program and helped me on many occasions when I needed to confirm certain details about the companies he worked with. Vale Barry.

Charles Barry Kitcher, born Cohuna, Victoria, 6 September 1930; died Melbourne, Victoria, 10 December 2019

Michelle Potter, 13 December 2019

* Interview with Barry Kitcher recorded by Michelle Potter for the Esso Performing Arts and Oral History Project, August 1994. National Library of Australia, TRC 3102

Please consider supporting my Australian Cultural Fund project to help Melbourne Books publish Kristian Fredrikson. Designer in a high quality format. Donations are tax deductible. See this link to the project, which closes on 31 December 2019.