This is an expanded version of an article first published in ‘Panorama’, The Canberra Times, 7 July 2012, p. 15 under the title ‘an icon of dance’, and in The Saturday Age, 7 July 2012, p. 24 with the title ‘In matters theatrical, Helpmann’s ideas soared above Patrick White’s bizarre flights of fancy’.

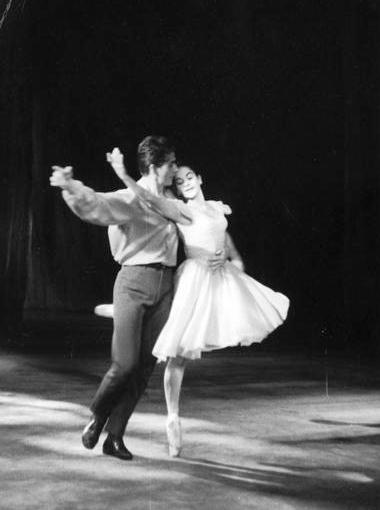

As part of its forthcoming Icons program, the Australia Ballet will restage Robert Helpmann’s 1964 work, The Display. I am curious to know how this work will stand up choreographically and theatrically now that close to 50 years have passed since it was conceived. The old black and white ABC studio recording shows a work that could still be gripping today with the right cast and informed coaching.

But I am also fascinated by the stories that surround the creation of The Display. Helpmann claimed, so the Australian Ballet’s current promotional material says, that The Display was inspired by a dream he had in which he saw his friend and theatrical colleague, Katharine Hepburn, naked on a dais surrounded by lyrebirds.

Helpmann and Hepburn came to Australia together in 1955 as the leading actors with a Shakespearean company sent out from London by the Old Vic. Hepburn, who toured in Australia for a period of about six months, was fascinated by the habits of the lyrebird, which she saw on a trip to Sherbrooke Forest in the Dandenong Ranges, and she insisted that Helpmann come with her to watch the lyrebird in its mating dance. Helpmann later included a note in a program for The Display in which he maintained that the movements he eventually choreographed for the character of the lyrebird in his ballet were those ‘learned after many hours of watching this beautiful creature’. So the background was certainly there for Helpmann to dream the dream he is alleged to have had.

The storyline of The Display concerns a group of young Australians on a picnic in the bush. The men practise football moves and Helpmann drew on the services of Ron Barassi* of Melbourne and then Carlton Football Clubs to coach the dancers for this section of the ballet. In old-fashioned Australian style, the girls rarely interact with the men but sit together, chat and prepare the picnic. We first see the lyrebird, who is named the Male in the list of characters, dancing behind a gauze at the beginning of the ballet. Three main human characters emerge—the Leader of the young men in the group, the Outsider and the Girl. The Girl and the Outsider are attracted to each other but the men have been drinking and inevitably there is a fight over the Girl.

The girls in the group flee the scene and ultimately the Outsider is left lying on the ground following the aggressive actions of the Leader and his mates. The Girl returns to the scene of the picnic, as does the Outsider, and eventually the Girl is left lying exhausted on the ground following an attempted rape by the Outsider. The Male reappears and, with his tail feathers fully displayed, enfolds the girl into his plumage.

The Display explores themes of hostility and aggression in Australian society and Helpmann recorded that he had attempted to show the brutality that can emerge from gang behaviour. Some of Helpmann’s colleagues have also suggested that elements of the story are autobiographical. William (Bill) Akers, who created the dappled lighting for the ballet, recalled in an oral history interview in 2002 that as a youth Helpmann was thrown into the sea at Bondi by a gang who thought his clothing was ‘sissy’. He was, according to Akers, wearing plus fours at the time. Akers suggested that The Display reflected Helpmann’s feeling that he had always been an outsider in society

The ballet is strongly symbolic and the work’s sexual elements, both overt and suggested, occasionally incurred the wrath of some sections of society. Newspaper clippings in Helpmann’s scrapbooks indicate that, when The Display was shown in Glasgow as part of the 1965 Commonwealth Arts Festival, the Glasgow Presbytery made attempts to have the ballet banned, a move that was only narrowly defeated.

But the story behind The Display has more to it than what Helpmann and others have recorded to date. In fact, Patrick White was approached to write a scenario for the ballet and a cache of letters, which I chanced upon around ten years ago in a National Library collection, indicated that when White submitted the manuscript it was not to Helpmann’s liking, and not to the liking of the then artistic director, Peggy van Praagh, either. They rejected the manuscript. But what was contained in White’s submission remained an annoying mystery until just recently when, while looking for something else, I chanced upon a manuscript in the National Library entitled ‘A scenario for a ballet by Patrick White’.

What this manuscript reveals is that Helpmann and van Praagh had excellent theatrical reasons for rejecting White’s scenario. White’s story takes place in two separate settings, the Australian bush where initially a picnic takes place, and a ballroom in the country mansion of a family called Brewer. The Brewer daughter, named as the Girl in White’s cast list, is engaged to an Italian Count. The girl has an obsession with a Lyrebird and during the picnic leads the Count into the bush where they encounter the bird. At the end of the ball that takes place in the mansion, the Girl returns to the bush. During this scene it is revealed that she is naked (stage naked) under her black raincoat. She encounters the Lyrebird and with him dances what White calls ‘a dance of consummation’. The Italian Count follows, is enraged at what he sees, rapes the Girl and then strangles her. He is then arrested by a detachment of policemen.

Helpmann may well have given White an initial plot outline as the first excursion into the bush is redolent of Hepburn taking Helpmann with her to visit the sanctuary of the lyrebird, while the nakedness of the Girl when she returns to the forest even recalls Helpmann’s alleged dream. The Italian Count too may well be Helpmann’s Outsider, although he is an outsider on account of his nationality and only partly so by his behaviour as described in the White manuscript.

But despite the fact that Helpmann apparently disliked what White presented, he appears to have borrowed many features of White’s story, including perhaps the gauzes that became part of Helpmann’s production and that lift to reveal the sanctuary of the lyrebird. White’s manuscript contains all kinds of stage directions including directions regarding gauzes.

However, Helpmann, as the remarkable man of the theatre he was, clearly removed the more bizarre and the more literary features from the manuscript he received. ‘When the ballet opens’, writes White, ‘a grotesque fête-galante version of an Australian picnic is about to take place’. He continues, ‘As the dancers appear they have the air of embarking on something reprehensibly unusual. They are inclined to mock at their surroundings and to treat the whole occasion as a huge joke. LADIES are over-dressed in satirical versions of contemporary clothes … The OLDER PERSONNAGES are pompous and would-be refined, the YOUNGER PEOPLE rather gauche, if not hobbledehoy’. In The Display that went onstage in 1964 there are no Italian counts, no feeling of hobbledehoy, no pomposity, no murders, no policemen for example. Helpmann distilled the scenario and in so doing created a story that could be told simply and clearly through dance. White’s elaborate and somewhat convoluted story with its many literary descriptions of events and people was not an easy scenario to translate successfully into dance. Even White’s three suggestions for a title, ‘The stroke of feathers’, ‘The feather breast’, or ‘The double engagement’, have nowhere near the instant attraction of Helpmann’s eventual choice, The Display, an ornithological term referring, in the case of The Display, to the lyrebird’s mating dance.

The Display was not the first all-Australian ballet as Helpmann claimed when speaking to oral historian Hazel de Berg in 1964, but it did have an Australian creative team of the first order. Complementing Helpmann’s choreography were designs by Sidney Nolan and music by Malcolm Williamson. The lighting design by Akers included a number of new initiatives in theatre lighting. The work was visually and aurally evocative and an exceptional collaborative effort. Its strength also partly lay in Helpmann’s ability to create theatre by reducing a story to its essentials.

The ballet was dedicated to Katharine Hepburn but Patrick White’s involvement was, to my knowledge, not mentioned in 1964‒1965 programs and appears not to have been mentioned in published biographies of Helpmann.

© Michelle Potter, 7 July 2012

Please respect my copyright in this article and acknowledge it if the material is used elsewhere.

* Barassi is recorded as saying: In 1964 I had the great pleasure of coming to know Robert Helpmann through my involvement on his ballet ‘The Display’. In the dance there was quite a lot of football played and Robert asked me to attend rehearsals and advise the ballet dancers on the correct ways of playing Victorian Rules. I did so and although the dancers were impressively athletic, I immediately noticed that they were throwing the football around the room like rugby players. I told Robert this and he was absolutely mortified. From there he worked solidly to get every detail right, as his demand for excellence and accuracy was uncompromising.

Given the friendship between Patrick White and Sidney Nolan [certainly around the time of “The Display”s inception] I wonder who was first approached regarding the possibility of working on the ballet and did that person suggest their friend as a possible collaborator. Or did the canny management at the AB realise the publicity potential of a collaboration uniting such big contemporary names [Williamson/Nolan/White/Helpmann]. Michelle has mentioned White’s manuscript as containing “all kinds of stage directions including directions regarding gauzes”. I wonder did Nolan and White discuss possibilities at an early stage.

Your remark that perhaps Nolan and White could have discussed possibilities is an interesting one, as is the question of who was approached when, although at this stage I simply don’t have any answers. I hope one day some correspondence will emerge that will help and I hope it won’t take 10 years as it did to find the White manuscript! The discovery of the manuscript opens up so many avenues for further research.

On the publicity potential of such a big foursome I suspect that Helpmann was interested in publicising himself more than anything else but, yes, publicising Patrick White as part of the team would have been terrific for public relations. In fact someone who was in the company in the 1960s has said exactly that to me privately.

Another interesting side issue, which I did not include in the post or the newspaper article, is that Kristian Fredrikson remarked in his oral history interview of 1993 that he was given the task of copying Nolan’s designs for the back and floor cloths for Display to send to London prior to the company’s overseas tour in 1965. The cloths were to be painted up in London and the Australian Ballet felt that Nolan’s original art works were too valuable to be sent. So they had Fredrikson make copies. This would have been shortly after Fredrikson arrived in Australia from New Zealand when he was doing all kinds of odds and ends of work for the Elizabethan Trust. Fredrikson says that Nolan never knew! ‘Fakeroo’ he called it (not without some pleasure in his voice)!

I am not sure if I have mentioned it to you previously Michelle, but the ‘first’ administrative file maintained by Geoffrey Ingram for the Australian Ballet, which includes pre-1962 material up to ~1964, including I believe correspondence with Helpmann around The Display, is at the Performing Arts Collection. I located it amongst a miscellaneous collection of scrapbooks at the end of the unprocessed material that was part of the ABs ‘Australian Archives of the Dance’ when I worked there during 2010. The file also includes material relating to the establishment of the AB with correspondence between the AETT, J C Williamsons etc.; engagement of Peggy and Geoffrey; artistic/staffing decisions etc. I put a couple of items from it in the small Peggy exhibition I did, but I’m not sure if the file has received much sustained research attention since.

Thank you Nick. I will make further inquiries when I am next at the Performing Arts Collection. It’s worth filling in as many details as possible to what has turned into a very interesting story.

Did you by any chance come across material concerning Ron Barassi’s involvement while you were working at PAC? I was contacted by an Australian Rules researcher asking if I knew more. It would be good to fill in more on that side too. The Barassi quote I used in my post is part of a note from Ron Barassi in the program for Tyler Coppin’s play Lyrebird: tales of Helpmann but I have not yet turned up much more.

In reply to Adrian’s initial comment on this post, some interesting material has just surfaced. In the records of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust various letters and reports from Peggy van Praagh indicate that a meeting was scheduled in London between van Praagh, Helpmann, Nolan and White on 30 August 1963. Van Praagh wrote to Stefan Haag on 2 September 1963 saying that White had agreed to write a scenario because they felt he would provide ‘a dramatic touch’. Van Praagh intimated that the scenario would be received ‘in about a week’. In the same letter she noted that Nolan had already produced some designs, which she found ‘ravishing’, and that she and Helpmann had listened to various composers and had decided on Williamson. Later in her artistic director’s report to a meeting on 9 December 1963 between the Trust and the Australian Ballet she advised that they had decided to go with Helpmann’s version of the scenario because they felt it was ‘more suitable to the medium of Ballet’. Prior to that, however, van Praagh sent Helpmann a telegram from Australia on 11 October 1963 asking whether or not White’s name should be included on the program credits. I didn’t find a reply from Helpmann, although the answer was clearly ‘No’.

It is still not clear of course who entered the scene when, although it seems that Nolan may have preceded White and that Williamson was the final creative collaborator to come on board.

These further pieces of the puzzle are most interesting. The issue of who was involved first, adds to our attempts to understand the alchemy involved in a ballet collaboration. If Nolan had produced some designs for consideration at the London meeting, one wonders what, at that stage, had been the brief given to him regarding the proposed work. Had Helpmann already worked out the locations and general outline of the action. And, as I have suspected, was more interested in getting White involved for the cachet of his name. Or perhaps he really did think White could flesh out the vague ideas Helpmann had already given to Nolan. The way the action plays out in the completed work has that marvellous sense of being the only way possible. And that may have been facilitated by Nolan’s ideas of the gauzes, helping move the action around the forest locations easily.

I am sure Michelle is deeply immersed in these ideas regarding collaboration as she works her way through Kristian Fredrikson’s career. The role of designer can be such an important contributor to a work. For instance I feel that the Peter Farmer designs for “Manon”, which the Australian Ballet employ, cannot hold a candle to the original Nicholas Georgiadis designs used by the Royal Ballet which worked with MacMillan’s ideas to show a visual panorama of how a whole society from high to low is interlinked and how a woman had very few options in achieving a measure of independence. Farmer’s work reduces it all to the level of illustrative, pretty, opera-ballet.

The AETT records also contain some interesting minutes from an Australian Ballet management meeting held in Melbourne on 30 October 1963 in which it was noted that the Zoological Gardens had been consulted in order to establish ‘the veracity’ of Helpmann’s title. It was also recorded that the committee suggested ‘that Miss van Praagh also convey the name “The Displaying” to Mr. Helpmann’. Fortunately Helpmann must have declined to accept the suggestion.

I think you are right Adrian that the story unfolds in an inevitable way and it certainly wouldn’t have done so had the White scenario been followed. I also had an offline comment from someone who was with the company in the 1960s who confirmed my suspicion that White’s Italian Count was probably Helpmann’s Outsider. The comment was that Helpmann made it clear to those involved in the production that the Outsider was Italian (the era was a high point in European migration to Australia). Still lots to discover and I would especially like to find out just exactly when Nolan came in!

And on another note, yes, I think the Georgiadis designs for Manon are much stronger than those of Peter Farmer. I tend to think that Farmer’s designs for Giselle also reduce that work to ‘prettiness’.

Have never ever forgotten this incredible ballet. I worked at Channel 7 and seem to remember a group from there going to the Elizabethan Theatre (was it at Newtown?). Whatever ..have no idea of who my fellow attendees were now I am 78 …anyway was totally mesmerized and so wish I could have gone back again. For years my father would take to the Borovansky season at least once where Kathy Gorham, petite and dark haired and Peggy Sager, tall and red haired would alternate leads. For a child…it was magic.

Thank you Susan for your lovely reminiscences. Yes, the Elizabethan was in Newtown and I remember going to many performances there – often way up in the ‘gods’. Yes again, The Display was incredible in its day. Kathy Gorham was amazing in the lead. I also recall the Borovansky seasons. They were mostly at the Empire Theatre at Central. I was a huge fan of Peggy Sager and wrote to her once asking for a signed photograph, which she generously sent!

My wife and I were in the audience in Sydney back in the day and whilst neither of us were involved in the ballet world, we both remember graphically the production.

For me it cut deeply into my appreciation of our culture. I likened the performance to the power of Arthur Boyd’s depictions of Australia, including the graphic degradations and immersion that only a great painter can carry off. Dancing for me took me to another level of appreciation. Such talent. So appreciated and enduring.

Thanks for coming this info, Eric Poulter, a now resident of Tannum Sands in Central Qld.

Thank you for this fascinating read! What was the first all-Australian ballet? It appears that Helpmann’s claim about The Display has stuck.

Thanks for your comment Michael. It is hard to say which work should be regarded as the first all Australian ballet, and it brings up a whole range of issues about dance prior to the arrival of Europeans. But, one thing I can continue to emphasise is that Helpmann’s Display was not the first all-Australian dance work.

I gave a paper, some years ago now, on what I referred to as ‘the search for identity’ in Australian dance. I posted it on this website and it is at this link: https://michellepotter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/The-search-for-identity-text.pdf

I recall the occasion on which I presented the paper and the diverse reaction it received from the audience, which included First Nations’ people as well as others. If you read the paper you can imagine the reaction, but it also gives you an idea of what went on before Display, at least as far as non-indigenous choreography was concerned.