17 September 2018 (matinee). Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

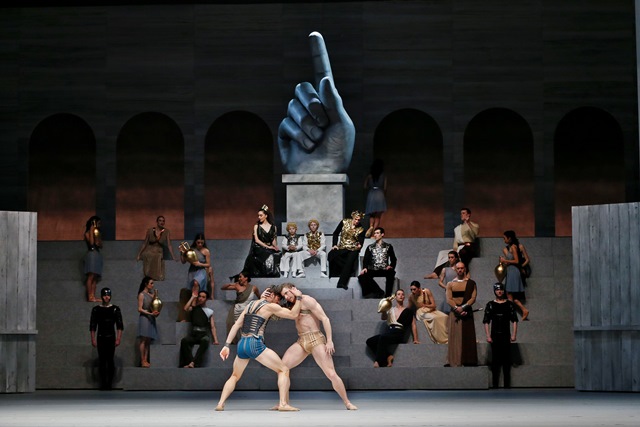

The high point in this new production of Spartacus is the set design by French artist Jérôme Kaplan. The costumes are, for the most part, beautifully designed too, but the sets are exceptional. In all three acts the overriding approach is a minimalist one, both in structure and colour. The design never overpowers the dancing, although it towers above it and has a real presence of its own. In the first act we are faced with a huge, dominant hand with one finger raised, positioned at the top of a very ceremonial-looking staircase. (The hand is modelled on the remains of a statue of the Roman Emperor Constantine who ruled early in the fourth century AD). Act II is distinguished by an elegant arched colonnade, and the closing act is just as powerful visually as, one by one, the bloodied slaves, who have been overcome by the Roman forces, stand on top of a diagonal row of huge rectangular blocks of faux concrete.

There are quite powerful references, too, to some current ideologies, which choreographer Lucas Jervies clearly sees as resonating with the power and dominance that characterised ancient Rome. As the work opens, for example, we see a street parade with rows of dancers clad in short, white, sporty outfits moving in unison and waving red flags. This Spartacus is for today, although it follows in basic terms the story of the rebel slave Spartacus and his wife Flavia.

I wish, however, I could be more positive about the choreography. Jervies engaged fight director and weapon and movement specialist Nigel Poulton to choreograph the fight scenes, which are pretty much a constant feature of this Spartacus. And Poulton clearly did a great job. No swords here. It was all punching, slapping, hands-on fighting, and quite violent for the most part. But beyond the fighting, I felt that Jervies did not have a strong feel for spatial patterns or for how to make the most of the space of the stage in general. Much of the choreography seemed very earthbound with, to my mind, an over-emphasis on angular arm movements. Then at other times it seemed too classical for words as in the dance for the slaves in Act II.

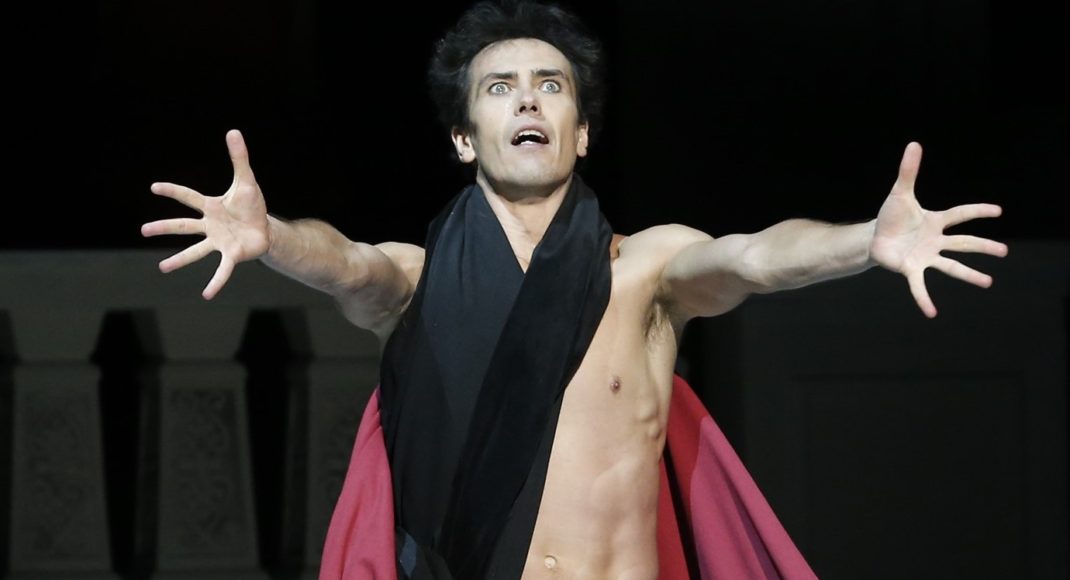

I had the good fortune, however, as often happens with a matinee towards the end of a season, of seeing main roles being taken by artists who are moving up the ranks. On this occasion Spartacus was danced by Cristiano Martino, a company soloist, and Flavia by Benedicte Bemet, also a soloist. They acquitted themselves well and Martino in particular, with his strong, muscular body, really suited the role. But for me, although they looked longingly at each other at times, their performance lacked passion, which may well have been a result of passionless choreography. Still, it was a real pleasure to see them perform as they did in such demanding roles.

Once again, however, my eye was drawn to Joseph Romancewicz in the corps (as it was earlier this year in The Merry Widow). New to the company this year, Romancewicz has such a strong stage presence and an innate ability to interact with his fellow dancers. Not only that, he is also able to draw the audience into the action. Wonderful!

Lucas Jervies’ Spartacus was interesting theatre but I kept thinking it would be better with spoken text than with dancing.

Michelle Potter, 19 November 2018

Featured image: Spartacus Act I. The Australian Ballet, 2018. Photo: © Jeff Busby