reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The power and excitement of Len Lye’s kinetic sculpture is clearly etched in the memory from visits I have made to the Govett-Brewster Gallery in Taranaki New Plymouth over the years. (Len Lye, a New Zealander, b.1901, began his arts experiments here but his subsequent career, based in New York through many decades, earned him a huge international reputation. His monumental sculptures with kinetic, aural and cinematic dimensions have been much discussed in publications by Wystan Curnow and by Roger Horrocks, and in a particularly fine documentary, Flip & Two Twisters, directed by Shirley Horrocks).

The Govett-Brewster gallery building is an inspired architectural presence in its own right. In tandem with the Len Lye Foundation, a major collection of Lye’s work is housed there and shown in sequential displays throughout the year. One of my visits I remember particularly well, since my companion and I lingered long in the gallery and then spent the rest of the afternoon in the cafe discussing Lye’s work, as well as the gallery’s achievement which originated with the vision of arts philanthropist Monica Brewster, who established it back in 1960s, independently of local council and other institutional governance.

That in turn led to my comparative thoughts about dance and the structure of performing arts companies versus independent artists—about who ‘owns’, who directs, who funds, who governs, who controls, who survives, who thrives—about how heritage repertoire is guarded, how programming is selected, how the welfare of the artists in companies is maintained, and how free-lance artists develop their work, who of them survive, who thrives, who is the dramaturg?—in a word, how dancers work, how dance works. All of these aspects are apparent to audiences, even if only subliminally, since they are reflected in the morale and calibre of each dancer we see in any given performance. It is said we get the politicians we deserve. Do we get the dances we deserve? Do the dancers get the recognition they deserve? As usual the answer is Yes & No.

Cameron McMillan, New Zealand born and raised, is a thriving surviving dance-maker. His current website is zinging testament to that. Born and raised in New Plymouth, he later trained at the Australian Ballet School and then joined RNZBallet in 1997, under Artistic Director, Matz Skoog. It was in 2000 that Cameron was noticed and singled out in glowing words in a review by Joan Acocella who saw him in Mark Morris’ Drink to me only with thine eyes—with the music most memorably played by pianist David Guerin onstage.(We had brought Acocella from New York to an Arts Festival here, under a Fulbright project on arts writing. The British Council had brought Michael Billington, drama critic, as part of the same program).

Acocella wrote that McMillan’s talent was striking already but that his potential was huge and that he could expect a major international career. She has proved not wrong. He choreographed Unsuspecting View for the Tutus on Tour of 2001, left RNZB not long after and has developed a stellar international career abroad, unfortunately little reported on back here, among several of our ex-pat choreographers whose work should be shared here but never is. Turid Revfeim’s Ballet Collective enterprise is soon to help redress that regrettable situation.

In 2015, I saw and reviewed a performance of Cameron’s work at the Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts where Ou Lu had appointed him choreographer-in-residence. It’s a poignant work, with a large cast of dancers, string quartet playing on stage. The theme concerns a corps-de-ballet dancer’s experience—a glimpse into something we all see but rarely discuss. The work would thrill audiences here, if only they had the chance to see it.

During the extraordinary times of Covid 2020, dancers and dance companies worldwide have been both staunch and flexible in streaming videoed responses to the wild changes in their lives and work. In some cases that has brought publicity and exposure they could never have dreamed of, and we have been offered access to extraordinary choreographic riches—Saarinen’s Borrowed Light, Lin Hwai Min’s Moonwater, Marston’s The Cellist would be some of the finest examples—though we have probably all seen enough of the dances videoed on a mat in the living room or on the patio—as a message of dancers’ resilience they’re fine, but as choreography they were mostly short of the mark.

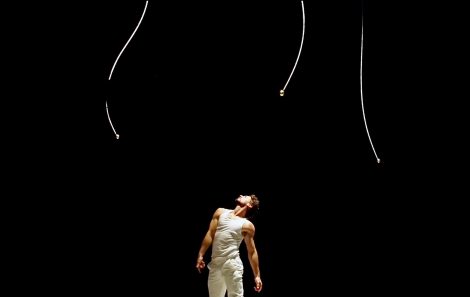

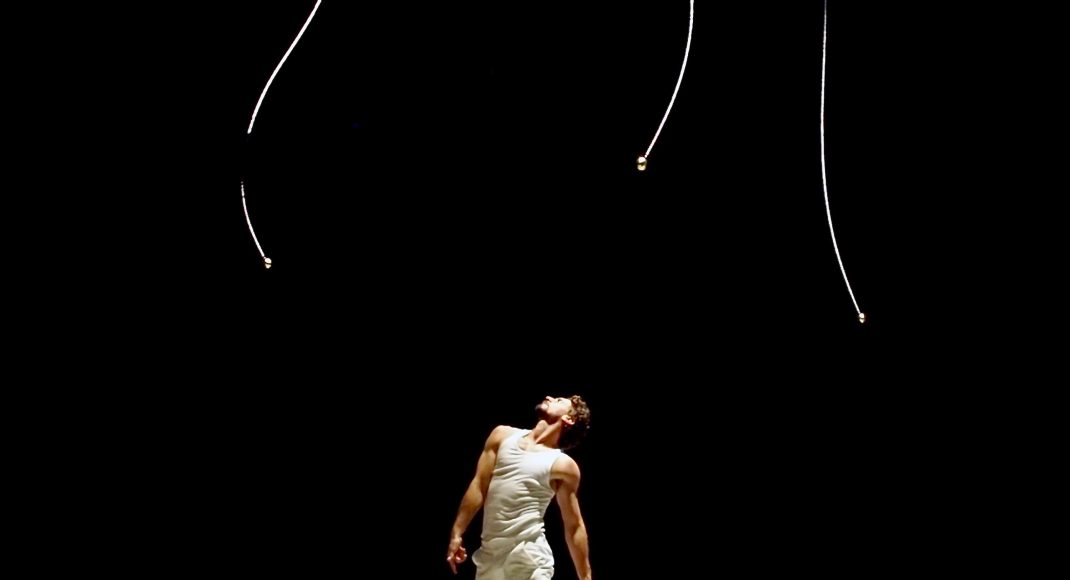

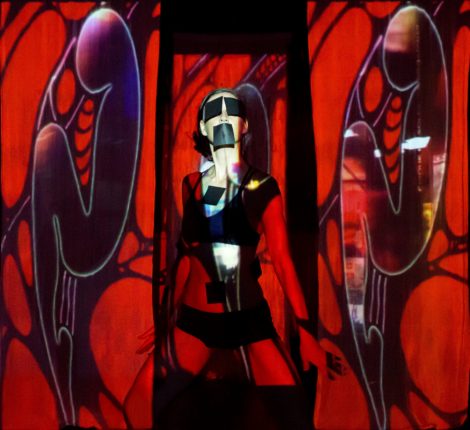

Cameron McMillan, in collaboration with the Govett-Brewster Gallery, has made a work in response to Len Lye’s Sky Snakes, which had its premiere exhibition in February 2020. Beneath Sky Snakes is an absorbing choreographic response to a sculpture that was moving already. The dance has a man on the ground, beneath a sky with huge forces of stalactite proportions. Tempo Dance Festival, an annual Auckland season, enterprisingly made the video available during this year’s digital season since the live program was cancelled. The choreography is yet in early stages of the film treatment it deserves but the dance shows a performer still moving with the mesmerising fluidity that Acocella described back in 2000. Perhaps a Govett-Brewster commission to Cameron could see a series of dances relating to other of Len Lye’s works. We all benefit from writing, talking, thinking about and remembering good dancing. Malo and Manuia

Jennifer Shennan, 11 September 2020

Featured image: Cameron McMillan in Beneath Sky Snakes, 2020. Screenshot