15 May 2024 (matinee). Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

Études and Circle Electric—it is hard to imagine two more different ballets (or perhaps dance works is a better expression than ballets). But they were the two works that shared the Australian Ballet’s Sydney program in May.

Danish-born Harald Lander choreographed Études in 1948 for the Royal Danish Ballet. It is essentially a non-narrative work (an unusual departure for the Danish company at that time) and is based on the structure of a ballet class. It begins with exercises at the barre and moves on to centre work building up to various, often complex, aspects of a class. There are many moments when we can see the relationship between class work and the art of ballet as it appears onstage. This happens as the choreography develops patterns and groupings of dancers, and also in references to other well-known productions, including the Danish classic, August Bournonville’s La Sylphide.

Circle Electric, on the other hand, is a newly commissioned work from recently appointed resident choreographer for the Australian Ballet, Stephanie Lake. The official synopsis says that the work ‘starts as a microscopic investigation of the intricate and the intimate, ultimately expanding to encompass a telescopic view of humanity.’

Circle Electric opened the program and for a moment it looked promising as two lines of dancers, positioned close together and wearing startling costumes (designer Paula Levis), held their arms to the front with fingers dramatically stretched out, then lifted the arms skywards, heads looking up expectantly.

But suddenly the dancers leaned forwards/downwards and engaged in a weird set of shivers, shakes and odd poses. They reminded me of animals in a zoo to tell the truth. Then they stretched upwards again, and dropped down again. This would not have been so bad had there only been one or two iterations of the up/down construction. But it went on and on and on. It was, admittedly, broken up between repeats with duets from other dancers (costumed quite differently) coming out from the wings but then rushing back before the up/down bit began again. Why repeat so many times? It was just frustrating to see it over and over and over again.

The frustrations continued as the work progressed. The many sections that followed seemed not to relate to each other and, when we got past the ‘intricate and intimate’ bit, crowds of dancers came together as a group of some kind and shouted across the stage to each other. Then they turned on the audience and shouted at us. Why?

Then there was the length of the piece. After a 1:30pm start, interval came at about 2:45pm. That’s 70+ minutes of what seemed like disconnected material. It was just too long and much repeated material could easily have been removed. A 30 minute piece perhaps?

The best part of Circle Electric was the outstanding dancing. The bodies of the highly trained dancers of the Australian Ballet can adapt pretty much to any style and they did adapt beautifully to Lake’s individualistic contemporary style.

After Circle Electric, Études was blessed relief. It has an engrossing beginning with its choreography reflecting exercises at the barre made to look so theatrically engaging with shaded lighting and moments when only feet, or some other sections of the body, are lit up. What follows is equally engrossing as it leads us through more examples of ballet technique put side by side with reflections on what makes it to the stage. It is a technically demanding work and there were times when a few wobbles occurred. But basically it was a thrill to watch. All I want to say is, ‘What a relief!’.

I find it hard to understand how David Hallberg would appoint a resident choreographer whose creative impulses can deliver something like Circle Electric, even more so when looking back at the choreographers who have held the position of resident choreographer over the past decades (going way back to Maina Gielgud’s tenure as director). Dance must move ahead for sure, but 70 minutes of dance that seems composed of sections and sections of movement that appear not to have any overall coherence just doesn’t cut it for me (especially when I paid $215 for my ticket).

Michelle Potter, 17 May 2024

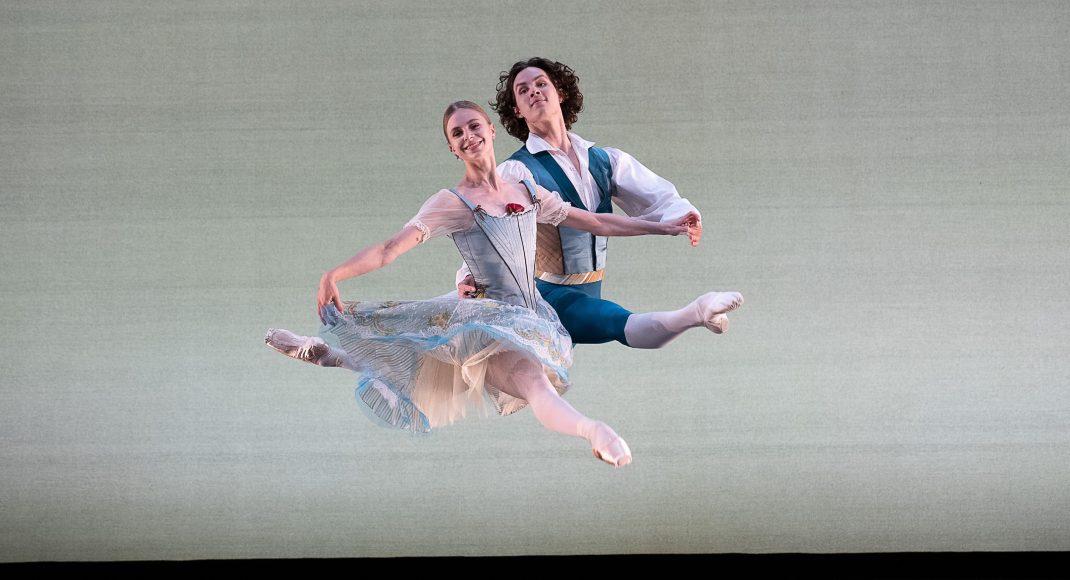

Featured image: Artists of the Australian Ballet in an early moment from Etudes, 2024. Photo: © Daniel Boud