18 July 2024. Bangarra Dance Theatre, Canberra Theatre.

In Canberra I had a rather different view of the production of Bangarra’s Horizon from the one I had in Sydney back in June. When I arrived at the Canberra Theatre to collect my tickets there was only one ticket in the envelope , despite the fact that I had officially been allocated two and did in fact have a guest with me. I was reallocated seats and ended up in row W very much on the side—not a position where critics usually sit! But in fact it gave me an interesting view of some aspects of the show, in particular a good view of the overall picture that was being presented, which gave added strength to some of the visual elements. While I much prefer to be a little closer, and hope the Canberra Theatre Centre can manage to get things right next time, all was not lost.

My review of the Canberra opening of Horizon was published online by Canberra’s City News and can be accessed at this link. Below is a slight enlarged version of that text.

Horizon is Bangarra Dance Theatre’s first mainstage, international collaborative initiative. It centres on aspects of Australian and Aotearoa New Zealand dance practice as those aspects reflect traditional society and culture.

The major part of the show is The Light Inside, a work in two sections. The first, ‘Gur Adabad/Salt Water’, is choreographed by former Bangarra dancer, Deborah Brown, whose family connections are in the Torres Strait Islands. The second is ‘Wai Māori/Fresh Water’, created by choreographer and director of Auckland’s New Zealand Dance Company, Moss Patterson, who grew up in the area around Lake Taupo on the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. The Light Inside is preceded by Kulka, a short work by Sani Townson, former Bangarra dancer and now Youth Programs Coordinator with the company.

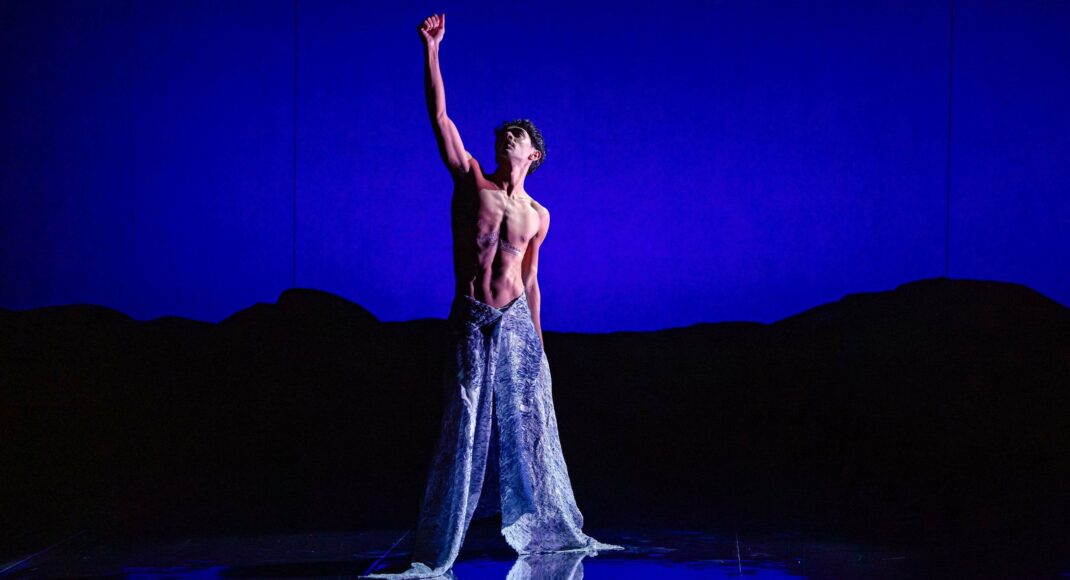

The focus of Kulka is nighttime with emphasis on the fact that much of Torres Strait Islander society abounds in traditional songs and dances about constellations that guide the totems and clans in the society. A leading role was taken by Kassidy Waters while a highlight was a trio danced by Lucy May, Bradley Smith and Kallum Goolagong, which centred on the role of the Crocodile God in Townson’s clan. A feature of Horizon was a projection that acted as a kind of backcloth and mirrored the performers as they danced. Kulka introduced us to this mirror-like effect, which was continued, although slightly differently, during The Light Inside.

Deborah Brown’s ‘Gur Adabad/Salt Water’ focuses on the relationship between Torres Strait Islander communities and the sea. An exceptional introduction to the work came from Daniel Mateo. It looked back to the work of a 19th century anthropologist as he recorded aspects of Torres Strait Islander culture on wax cylinders. Another highlight was ‘Blue Star’, an exceptionally performed solo by Lillian Banks telling of a seasonal change when moisture in the air makes the stars turn blue and twinkle, which becomes a guide for the seafaring peoples of the region.

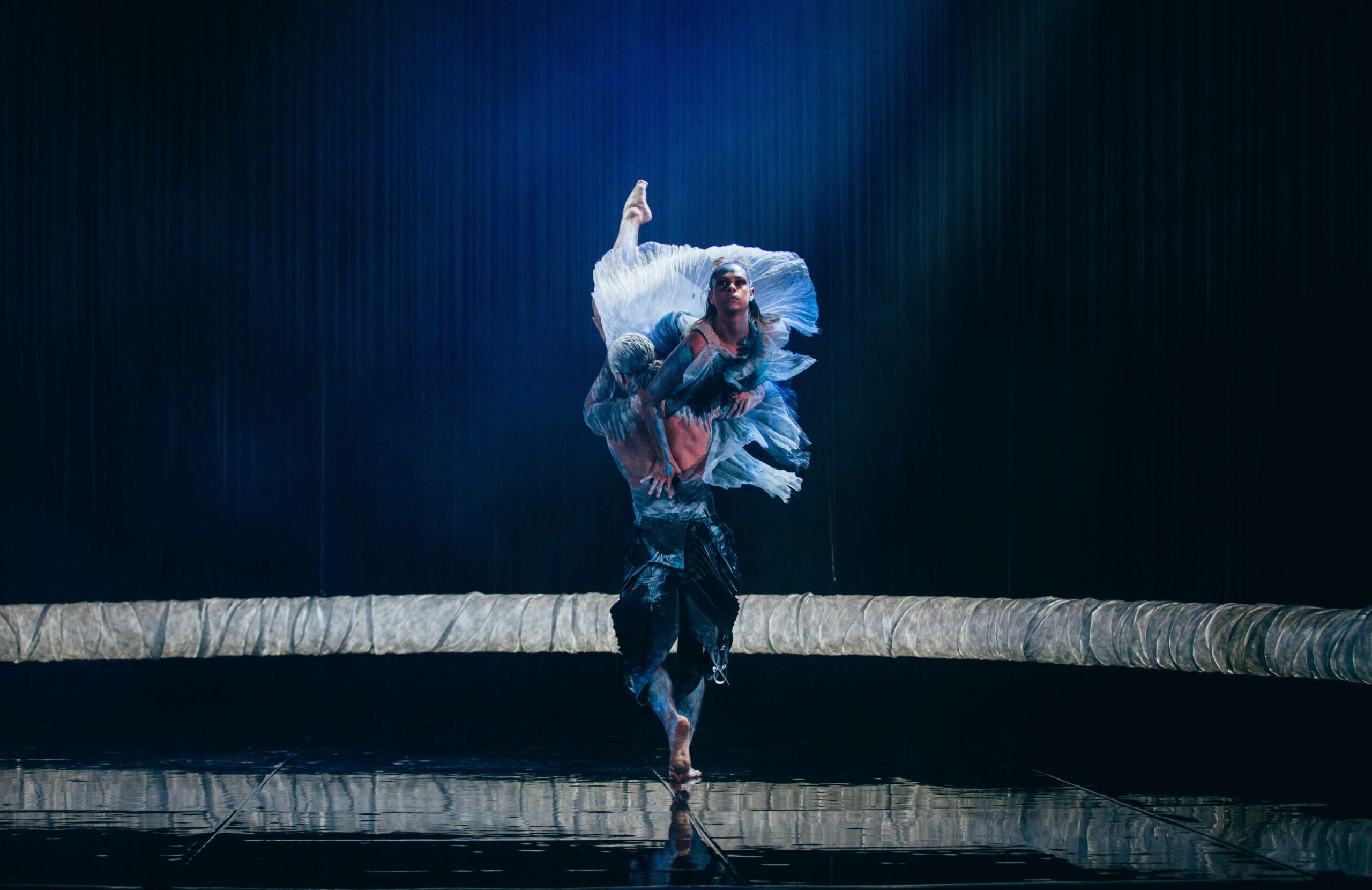

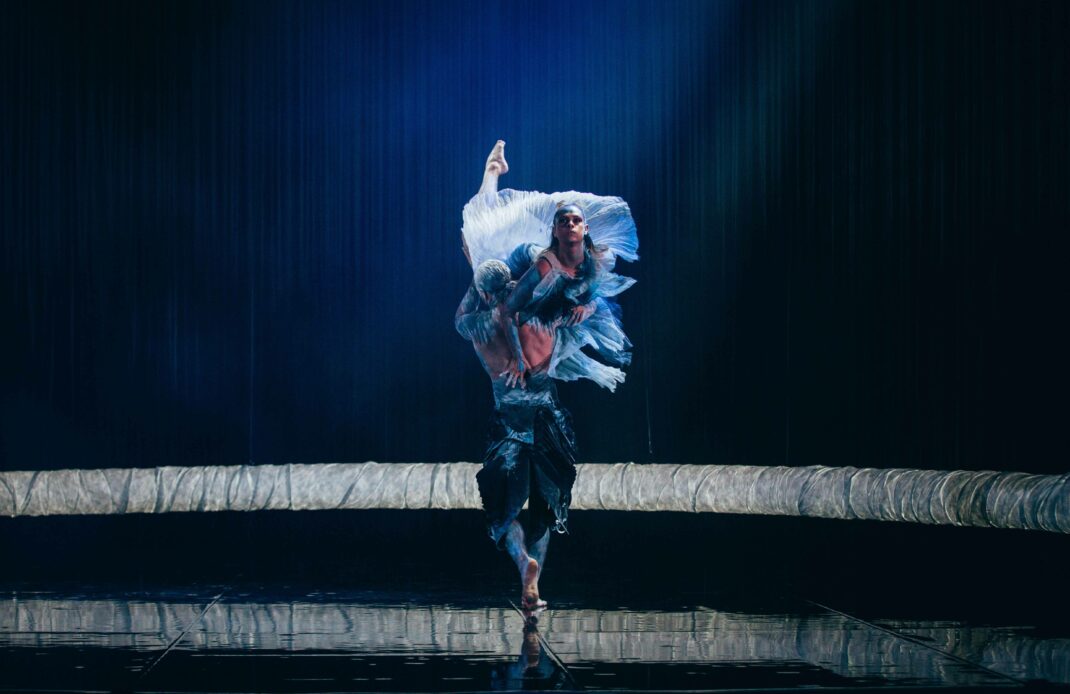

The standout work on the program, however, was ‘Wai Māori/Fresh Water’, Moss Patterson’s section of The Light Inside. I first saw this work in Sydney at its world premiere in June. Then I couldn’t stop thinking about the relationship this new work had with the Māori haka. I was repeatedly reminded of football matches between Australia and New Zealand that are inevitably preceded by a haka. But the Canberra show seemed very different. After a month of performances in Sydney, the dancers had clearly absorbed the powerful and individualistic nature of Patterson’s choreography. The work was intensely moving and dramatic. Those qualities were clearly transmitted through the bodies of the dancers. They were proud. They were aggressive. They were strong and determined as they took their place in the world. Football memories were gone.

The work ended in a quieter fashion with the ensemble dancing to suggest peace and communication. But the strength and power of Patterson’s ‘Fresh Water’ remained and had clearly inspired the audience. Cheers rang out as the evening came to a close.

Horizon is an admirable undertaking and, as is usual with Bangarra productions, the collaborative elements were exceptional. Original scores were created by Steve Francis, Brendon Boney and Amy Flannery. Costume designs came from Jennifer Irwin and Clair Parker, set design from Elizabeth Gadsby, and lighting from Karen Norris.

Michelle Potter, 23 July 2024

Featured image: Kassidy Waters and dancers of Bangarra Dance Theatre in a moment from The Light Inside. Bangarra Dance Theatre, 2024. Photo: © Daniel Boud