The Royal Danish Ballet has had a close relationship with Jacob’s Pillow, that beautiful dance venue in the Berkshires in Massachusetts, since the 1950s. Ted Shawn, founder of the Pillow, was even given a knighthood by the King of Denmark in 1957 for initiating the cultural exchange that brought the Danes to the attention of an American dance audience.

Most recently the company, presently led by Nikolaj Hübbe, performed at the Pillow in 2018. Highlights from that 2018 program have just been streamed by Jacob’s Pillow as they, like all of us around the world, attempt to manage a situation in which live performance is pretty much impossible. The streamed program consisted of the pas de sept from A Folk Tale, the pas de deux from Act II of La Sylphide, the pas de deux from Act I of Kermesse in Bruges, the pas de deux from Act II of Giselle, and the pas de six and tarantella from Napoli. With the exception of Giselle, all had choreography by August Bournonville, whose unique style has become synonymous with the Royal Danish Ballet (although of course these days the company dances the choreography of many others).

This program was danced without scenery, which put the focus firmly on the choreography, and it enabled us, I think, to look beyond the complexity of those incredible beaten steps and the beautiful ballon that has always seemed to be the cornerstone of the Bournonville technique. Not that those particular features, and the complexity of the combinations of steps, was unclear, but other aspects of the technique became more apparent (at least to me). I was moved especially by the use of the upper body, the epaulement and the incline of the head; by the simplicity of some of the steps that provided a contrast to the more complex ones; and by the use of academic positions of the arms—constant use of bras bas, and third position captured my attention in particular.

I loved too the interactions between the dancers when they weren’t dancing. At times they were casual onlookers, at others they applauded their colleagues efforts, or they showed them off to the audience. The dance became a regular human activity rather than an eisteddfod-like showcase.

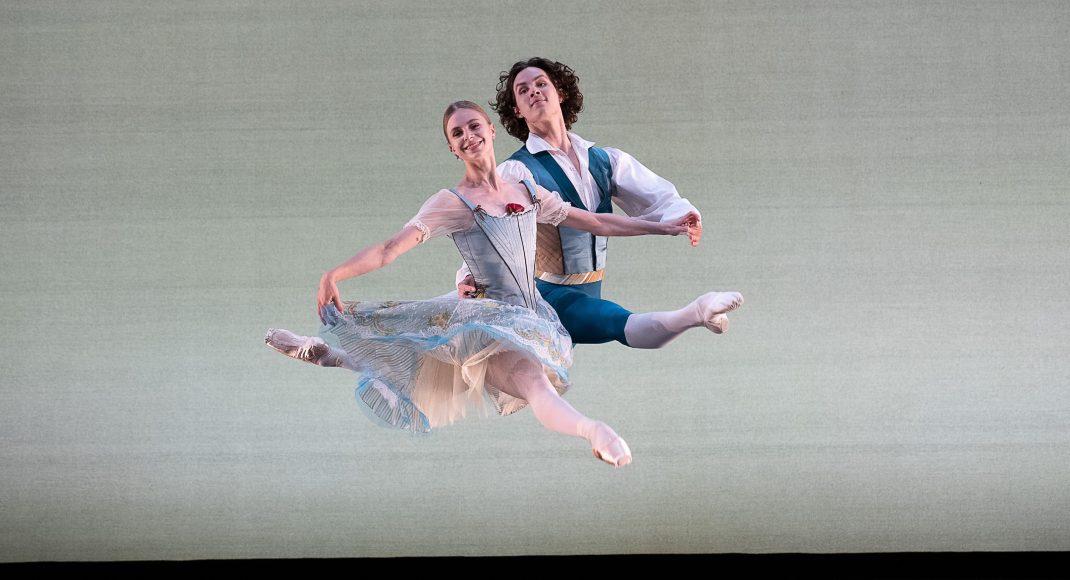

While Napoli was the highlight as the closing work, and it was danced with strength, joy and vibrancy, I admired in particular the pas de deux from Kermesse in Bruges. Andreas Kaas had great presence on stage and an exceptional ability to connect with his partner, Ida Praetorius on this occasion. They gave the pas de deux a real storyline. But that pas de deux also demonstrated how duets from Bournonville often involve a particular structure in which the partners often dance side by side, sometimes in unison, sometimes executing the same steps next to each other but as a kind of mirror image. There are fewer high lifts as a result (although, of course, they are not missing).

The one jarring issue for me occurred in the pas de deux from La Sylphide danced by Amy Watson and Marcin Kupinski—nothing to do with the performance itself but with the shirt Kupinski wore. It seemed to be made of very light material and every time he jumped (which was often) it moved up and down to the extent that I kept thinking he was lifting his shoulders and destroying the line of his body. He wasn’t and his performance in Napoli showed his physical composure. But in La Sylphide that shirt made it seem as if he wasn’t in control.

The one non-Bournonville work, the Act II pas de deux from Giselle, seemed a little lack-lustre to me. Perhaps it did need something else—if not some scenery then the presence of Myrthe. I did admire, however, the way J’aime Crandall used her arms with so much expression.

But shirts and lack-lustre aside, what a wonderful hour of dancing. And follow this link for an excerpt from A Folk Tale courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive.

Michelle Potter, 1 August 2020

Featured image: Andreas Kaas and Ida Praetorius in the pas de deux from Kermesse in Bruges. Royal Danish Ballet, 2018. Photo: © Christopher Duggan

Afterthought (from an Australian perspective): Given the Australian connections in the Danish Royal Family, perhaps we need to persuade the Queensland Performing Arts Centre (QPAC) to make an effort to partner with the Royal Danish Ballet in QPAC’s very successful International Series. The Series has so far seen American Ballet Theatre, the Paris Opera Ballet, the Royal Ballet, La Scala Ballet, the Bolshoi Ballet, and others, come to Brisbane for a summer season. The Royal Danish Ballet would be a magnificent addition.

What a thrill if Royal Danish Ballet could be brought to perform in Australia. That would certainly warrant a trip across the Tasman — (and possibly be worth whatever quarantine conditions might be imposed, though let’s hope none).

Your mention of Ted Shawn’s welcoming of Inge Sand and other Danish dancers to Jacob’s Pillow strikes resonance this side of the Tasman too. Poul Gnatt was only 30 when he arrived here in 1953 to found the New Zealand Ballet. (He had been a celebrated Principal with RDB among his peers Frank Schaufuss, Fredbjorn Bjornsson, Erik Bruhn). A trojan decade followed as he established the company throughout the country, building up a stalwart army of Friends from the first year (their poignant story needs to be told sometime since it seems to have been forgotten…) Gnatt brought his sister Kirsten Ralov and her husband F.Bjornsson, to perform a Bournonville programme with New Zealand Ballet. — (Theirs was the first complete Napoli to be produced outside of Denmark, and indeed Far From Denmark).

Gnatt was in 1963 offered a Government grant (Leon Gotz was Minister of Internal Affairs at the time) to fund a refresher return trip to Denmark to renew contacts there and make plans for further repertoire development here. He made all the appropriate arrangements including travel bookings but then was told the government had changed its mind! Furious beyond words, he left anyway. How did he finance the trip? Ted Shawn invited him to teach and give lecture dems at Jacob’s Pillow! There are several letters from Poul to “Dear Pappa Shawn” among the Gnatt papers at the Turnbull Library here. Ballet history is less of a straight line and more of a rond-de-jambe. Poul’s beloved Bournonville heritage was the trunk from which subsequent branches of ballet style were developed here. It’s a proud heritage and one that should be remembered with joy.