Tributes from Michelle Potter and Jennifer Shennan

From Michelle:

It is with immense sadness that I pass on the news that esteemed dance writer, Joan Acocella, has died in New York City aged 78. She was one of the best dance writers I have come across. Why? Her writing style was always eloquent, elegant and engaging. Her research for her writing seemed to know no bounds. And her way of thinking about dance was profoundly different from most dance writers.

In the introduction to her book, Twenty-eight artists and two saints, a collection of essays written initially for other printed sources (largely but not exclusively for The New Yorker), she explains her point of view in relation to the essays included in the book. Her approach addresses what she calls ‘the pain that came with the art-making, interfering with it, and how the artist dealt with this’ rather than what she sees as a common belief that artists endure ‘a miserable childhood and then, in their adult work, to weave that straw into gold’.1

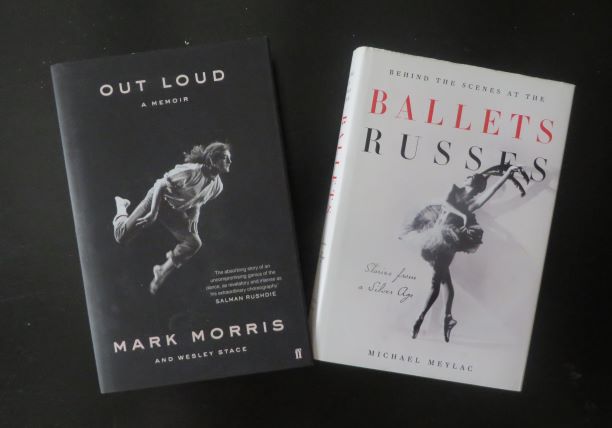

Her 1993 publication Mark Morris also has a beautiful slant on the idea of biography. In her Author’s Note that precedes the biography itself she writes:

My goal was to provide an account of [Morris’] life and a guide to his work, but what I wanted most was to give a portrait of his imagination—an idea of how he thinks, or how he thinks the thoughts that lead to his dances.2

Elsewhere on this site I have written about Mark Morris with the words:

Acocella knew Morris’ background, sexual, emotional, family and otherwise, but didn’t dwell on it as such. Instead she showed us so clearly how that background could give us an insight into his works. I especially enjoyed her chapter on Morris’ time in Brussels. True, she mentioned the dramas, but also the successes so that it became a balanced account of that time. She also set it within a context of European approaches to viewing dance and contrasted these approaches with those she thought were more typical of American thoughts. Her biography of Morris is so worth reading.

Then there is her fabulous editing of Nijinsky’s diaries in which she gives us the real thing, not an expurgated version as did Nijinsky’s wife, Romola.

But I have one personal memory that has always stayed, and always will stay with me. While working in New York I was giving a media introduction to a New York Public Library Dance Division exhibition INVENTION. Merce Cunningham and collaborators. I was about to use a quote from an article by Acocella on the Cunningham production Split Sides. As I looked up and out to the audience, there was Joan Acocella smiling beatifically as her name was mentioned and somehow seeming to stand out from the others in the auditorium. A shining moment and a special memory of an exceptional lover of dance.

From Jennifer:

In 2000 Wellington’s International Festival of the Arts proposed an Arts Writing initiative in which the British High Commission brought out Michael Billington, long-time theatre critic for The Guardian, and Fulbright New Zealand brought Joan Acocella, dance critic from New York.

(At first the invitation had gone Deborah Jowitt but, as the deadline for her book on Antony Tudor was approaching, she declined. Jenny Gill of Fulbright asked me to suggest an alternative. I had met Joan Acocella in 1980s while studying in New York and many of us were delighted when she accepted the invitation).

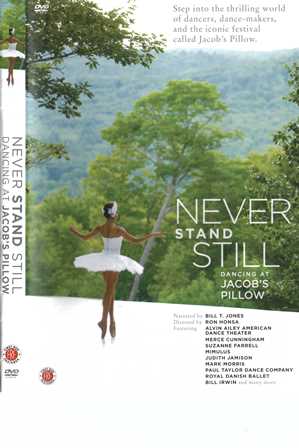

I requested that Joan first be taken to Dunedin where RNZBallet were performing a season including halo by Douglas Wright, and Mark Morris’ Drink To Me Only With Thine Eyes, and her resulting review was full of interest. Then in Wellington Joan conducted a weekend dance-writing workshop—some dozen of us attended NDT’s Mozart program, wrote a review overnight, delivered those to Joan at her hotel before breakfast then met mid-morning to hear her comments on our various reviews. It was a fascinating experience and I stlll use my notes from that weekend.

I also arranged for Joan to give a lecture at NZSchool of Dance where she spoke about Nijinksy. (Joan’s edition of Nijinsky’s Diary reinstates all that his wife Romola had omitted from her early publication of it. Her biography of Mark Morris is also an insightful study of an iconoclastic artist).

In the years of Joan’s sparkling dance and literature writings for the NY Review of Books, and for The New Yorker, there are many classic pieces, but her trip with Baryshnikov on his first return to Riga is probably the most indelibly etched of them all.

A very great dance writer indeed. It was a privilege to have known and worked with her.

Joan Acocella: born San Francisco, 13 April 1945; died New York City, 7 January 2024

Michelle Potter and Jennifer Shennan, 11 January 2024

Featured Image: Joan Acocella photographed in New York. Photo from The New York Review of Books.

1. Twenty-eight artists and two saints (New York: Vintage Books, a Division of Random House) 2007), p. xiii. Not all the subjects in this book are dance artists but those who are include Lucia Joyce, Vaslav Nijinsky, Lincoln Kirstein, Frederick Ashton, Jerome Robbins, Suzanne Farrell, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Martha Graham, Bob Fosse and Twyla Tharp.

2. Mark Morris (New York: Farrer Straus Giroux, 1993), unpaginated.

Various obituaries are available on the internet.