The year everywhere saw curtailment of a number of dance events but the resilience in dancers’ responses still gave us plenty of highlights to savour …

Ballet Collective Aotearoa launched its long-awaited premiere season, Subtle Dances, in the Auckland and Dunedin Arts Festivals early in the year. Artistic direction of BCA by Turid Revfeim, to establish a new national independent ballet enterprise, is supported by her troupe’s pioneering and committed spirit that refuses to let funding challenges affect their vision, as further festival bookings eventuate and new sponsorship initiatives are waiting in the wings. BCA achieved an outstanding professional level of dance and music presentation with this triple-bill that premiered choreographies by Sarah Knox, Cameron Macmillan and Loughlan Prior, in collaboration with the New Zealand String Trio, who played onstage throughout. This was chamber performance of the highest order, and impressive that the two arts could bring such coherence to a triple-bill. It was further affirmation to see Abigail Boyle, nationally treasured dancer, performing at her peak. Young company member Kit Reilly is one to watch out for (he has recently received the inaugural Bill Sheat Memorial Award for a dancer prepared to commit to New Zealand identity in their career).

Later in the year Loughlan Prior achieved what is arguably his finest choreography—Transfigured Night, beautifully themed to the Schoenberg score, performed by New Zealand String Quartet in a NZChamber Music national tour, in an impressive staging where musicians and dancers again shared the stage space. The calibre of choreography, fine dancers and fabulous musicians ensured that the totality was greater than the sum of its considerable parts. That doesn’t happen just by cutting the stage into two halves, but grows out of the skill and vision of the choreographer, and willingness of the musicians to take risks (NZSQ have always been up for that). Laura Saxon Jones, another much valued New Zealand dancer, was here in her prime, as Prior, who knows her work well, intuited exactly how to create a searingly memorable role for her. Thanks to inspired set and costume design by William Fitzgerald (who also danced in the work), the unlikely space of the Fowler Centre was transformed into a grail of poignant and poetic beauty. At the end, audience members, primarily music followers, were either on their feet or reduced to tears by this outstanding work, which would hold its strength in any venue worldwide. Perhaps it is music audiences that will enlarge a future following for dance as they find music treated with equal respect as choreography, without distracting interruptions of shouting and whistling that haul balletic virtuosity out of the context of choreography (as though dancers need encouragement to tackle the next entrechat or pirouette).

Lucy Marinkovich brought her remarkable Strasbourg 1518 back to Circa Theatre after its premiere season there was cut short last year. It remains the most powerful experience of dance theatre seen here in a very long time, and its Auckland season also made huge and visceral impact. Lucien Johnson’s sound design plus saxophone drove the performers into the stratosphere. I remember the narrator from the original production, France Hervé, for the remarkable transition within her role that edged its way through the performance. No easy way to turn that alchemy into words.

Bianca Hyslop choreographed and Rowan Pierce designed Pohutu, performed for the Toi Poneke gallery, a highly effective setting for a work of empathy with unfolding references to both geographical landscape and mental inscape.

The New Zealand School of Dance graduation offered a program of interesting contrasts within the classical and contemporary vocabularies, and I felt thrilled to encounter the choreographic instinct and potential of Tabitha Dombrowski’s new work, Reset Run.

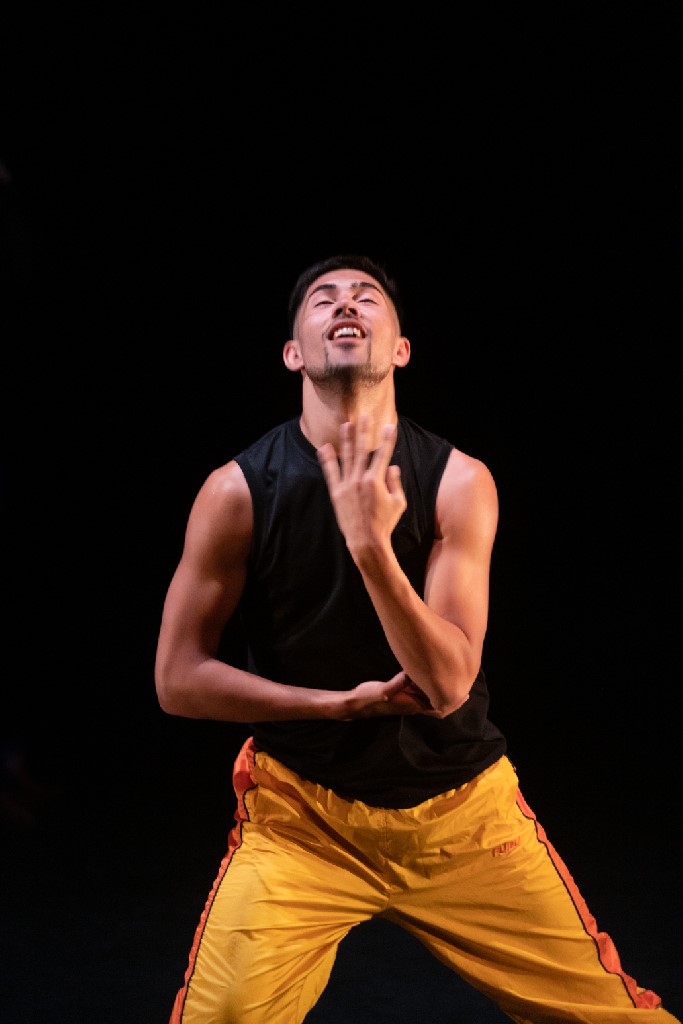

Vivek Kinra’s company Mudra presented Navarasa, to his customary highest standard of Bharata Natyam, a consistent contribution to Wellington’s artistic life for decades. One of my favourite things is to observe a dance class, to sight the seeds planted that over time grow into performance. It’s one of the ways to prepare for the privilege of writing about dance in its ephemeral, enduring path. Kinra is one of the most naturally gifted dance teachers across all genres in Wellington, in his command of discipline that is shared with, but not imposed upon, his students. In this Indian dance form there is a wonderful continuity between studio and stage which offers a cleansing and rewarding experience.

I attended a spirited gathering at Parliament, where a book documenting the Irish population resident in New Zealand was launched. Every address was laced with a song, as we are so accustomed to in Maori whaikōrero (oratory) and following waiata (song) but it was especially apparent here that Celtic dance is as readily available as song, poetry, literature, instrumental music—fiddle and pipes—as affirmations in Irish communication. No choreographer to be named here—just dancing from the heart.

The Royal New Zealand Ballet’s restaging of Liam Scarlett’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream brought us many poignant reminders of the premiere season in 2016 and its stellar cast. Previous artistic director Ethan Stiefel had initially proposed and negotiated with Queensland Ballet for the two companies to share a series of productions, which was a truly exciting prospect. Queensland Ballet did mount A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 2016 but after that, unfortunately, the project did not proceed further. But the calibre of choreography and design (Tracy Grant Lord) of Dream remains intact. It was Scarlett’s masterstroke to frame the plot with a prologue of the young child caught between fractious parents yet resolved by the epilogue, hence the genius to telescope a 500 year old theme into contemporary society. That Liam Scarlett died at 35, earlier this year, is something that Shakespeare, in heartbreaking tragedy, would be challenged to account for.

I watched on Sky Arts several sizzling programs of documentary/performance by Flamenco artists, memorably Rocio Molina. The best-made dance films for my eye are those of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan, superb record of the company’s prolific repertoire in perpetuity, and their viewings always prompt me to send a message to everyone in my contacts list to watch if at all possible.

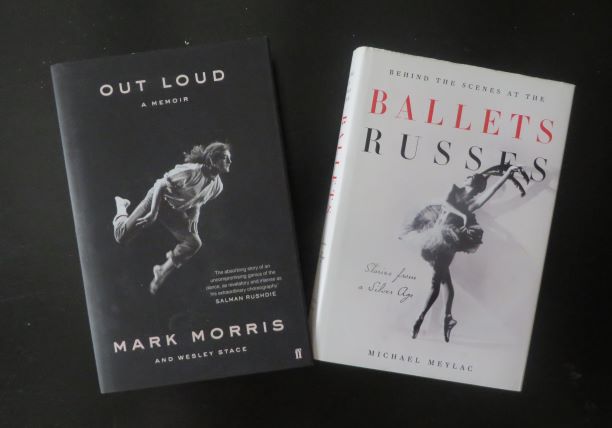

Dance reading helped fill some of the quieter stretches of the year—Michel Meylac on Russian Ballet emigrés was exactly what it claimed—whereas I found totally delightful surprise, when reading the fresh and fabulous Zadie Smith—Feel Free—to happen upon her essay Dance Lessons for Writers, in which she brilliantly couples and compares Fred Astaire & Gene Kelly … ‘aristocracy v. proletariat…the floating and the grounded …’; Harold Nicholas & Fayard Nicholas … ‘propriety and joy, choose joy…’; Michael Jackson & Prince; Janet Jackson, Madonna, Beyoncé; David Byrne & David Bowie; Rudolf Nureyev & Mikhail Baryshnikov… ‘the one dancer faced resolutely inwards, the other is an outward-facing —artist…’. It’s heartening to find such perceptive analysis from a writer who is not exclusively describing dance performances, but who can trace and evaluate how these technical and aesthetic qualities resonate with the rest of our experiences.

For the fourth Russell Kerr Lecture in Ballet & Related Arts, Anne Rowse brought her own 90 years alongside her decades of friendship with 91 year old Russell Kerr to trace their parallel careers—and what fabulously sustained careers those have been. The event was coupled with a celebration of Michelle Potter’s book, Kristian Fredrikson, Designer, generously supported by the Australian High Commission.

The same event also saw the launch of DNA—Dance Needs Attention, a networking enterprise to invite artistic associates to support each other as individuals in independent dance studies and writing projects. Among early tasks was the opportunity for me to read the manuscript of associate Ashley Killar’s forthcoming biography of John Cranko—a fascinating read and one certainly to watch out for.

2022 will see Patricia Rianne, in the fifth lecture of the RKL series, trace her own life and career—including the ballet, Bliss, that she choreographed after a Katherine Mansfield story, for New Zealand Ballet in 1986. There will be several seminars throughout following months in which we will celebrate Poul Gnatt’s arrival in New Zealand in 1952, when he first taught open classes in Auckland as the Borovansky Ballet toured here, before he founded the New Zealand Ballet the following year.

May we all be safe and sound through 2022… 100 years since James Joyce published Ulysees, TS Eliot published The Waste Land, Virginia Woolf is writing, Katherine Mansfield is writing… and Sergei Diaghilev invited Igor Stravinsky, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Erik Satie and Clive Bell to dine together in Paris at the Majestic hotel. Wonder what was on the menu that night. Choreographic scenario, anyone?

Jennifer Shennan, 21 December 2021

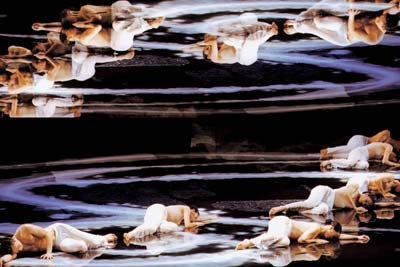

Featured image: Scene from Helix in Subtle Dances, Ballet Collective Aotearoa, 2021. Photo: © John McDermott