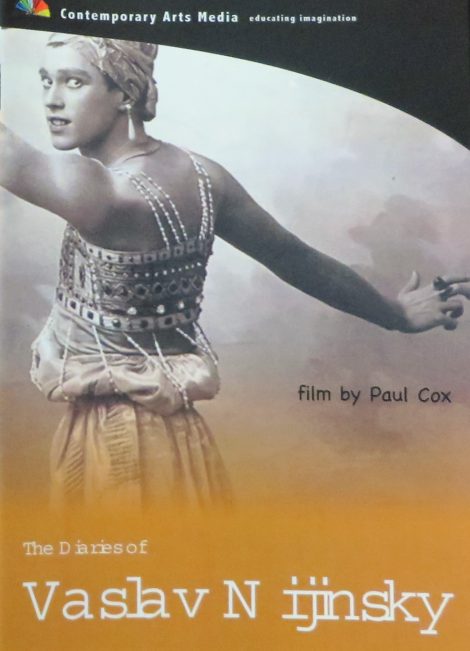

The death earlier in June of film maker Paul Cox sent me in search of a DVD copy of his film The diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky. The backstory is that Cox heard actor Paul Schofield on British radio reading from Nijinsky’s diaries (cahiers), which were first released in 1936 after having been rearranged and edited dramatically by Nijinsky’s wife, Romola.1 From that moment Cox was smitten and wanted to make a film based on the diaries. The making was a drawn-out experience (it took three years),2 but the film was eventually completed in 2001 and released in 2002. Cox has referred to it as a ‘cinematic poem’: it is certainly far from a documentary in the commonly understood meaning of the term.

Nijinsky began writing down his thoughts as a kind of diary on the morning of his last public performance, which he gave at the Suvretta Hotel in St Moritz on 19 January 1919. He wrote his last entry on 4 March that same year, the day he was to go to Zurich to see the psychiatrist, Eugen Bleuler, who would decide that he was suffering from incurable schizophrenia and who would advise, among other things, that he be admitted to a sanatorium. There are three exercise books of writing and drawing, with the first two books containing sections of Nijinsky’s own form of dance notation. The fourth notebook contains several letters to family, friends and others. The three diary books are held by the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. The fourth book of letters is held in Paris by the Department of Music, Bibliothèque nationale.

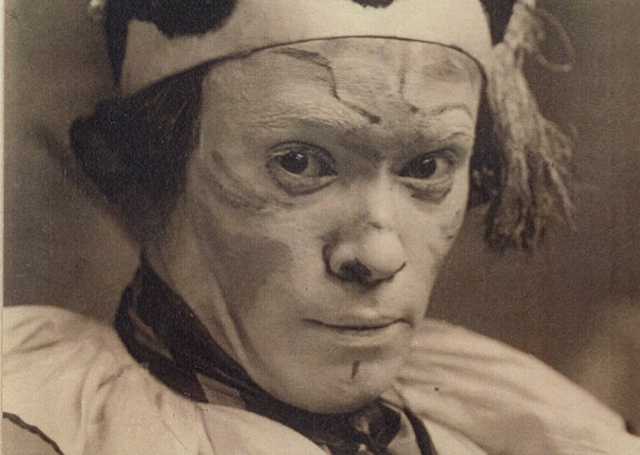

I found Cox’s film (which I must admit I had never seen before) absolutely mesmerising. It is in many respects a collage of images that flash past us, some of which return hauntingly throughout the film. Sometimes they are photographs of Nijinsky in his well-known roles for the Ballets Russes, such as the image at the top if this post, which shows Nijinsky as Petrushka. Sometimes they are images from nature, with flowing water and birds, in particular a crane, appearing frequently. Cox also plays with light and shade and there are many fleeting, emotive moments where shadows flicker over walls, water, and natural features of the landscape. The images reflect Nijinsky’s words as they are written in the diaries and are spoken as a voice over by Derek Jacobi.

The film begins with a funeral procession, Nijinsky’s funeral. As the coffin and the mourning party move down a pathway we see ‘ghosts’ of Nijinsky hovering in the background and sometimes merging with the funeral procession. They are characters Nijinsky played in the ballets that made him the famous male dancer that he was—the Spirit of the Rose from Le spectre de la rose, the Golden Slave from Scheherazade, the Faune from L’Après-midi d’un faune, and so on. These characters appear, disappear and reappear throughout the film, slipping between the other images, always reminding us of Nijinsky’s remarkable dancing career.

The dancing components, like the characters who hover around the funeral procession, are interspersed seemingly randomly between the flow of non-dancing imagery. David McAllister and Vicki Attard appear as the two characters in Le Spectre de la rose, while dancers from Leigh Warren and Dancers take on most of the other dancing roles. I admired Aidan Kane Munn’s ‘War Dance’, which he choreographed as a tormented, quivering solo and danced blank-faced. This was the item Nijinsky chose to dance at Suvretta House: ‘Now I will dance you the war … the war which you did not prevent.’ It is described by Joan Acocella (following Romola Nijinsky’s description) as ‘a violent solo, presumably improvised’ and analysed by Ramsay Burt in relation to Nijinsky’s thoughts on war and peace.3 I also especially admired Csaba Buday’s performance as the Faune in a version of L’Après-midi d’un faune choreographed by Alida Chase and set outdoors in a clearing surrounded by trees and bushes. There was an animal-like awareness to Munn’s reactions as the Nymphs passed by, and his closing scene with the veil was gentle yet blatantly sexual.

There is a kind of narrative component to anchor the imagery and dancing. We meet Romola and her parents and the various doctors who examined Nijinsky, for example. But we never hear them speak, although their body language and facial expressions give us clues as to how the story and their thoughts about Nijinsky are unfolding. Their presence forces us to face the reality that is behind the film.

The diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky is a truly beautiful, painterly film. Like John Neumeier’s Nijinsky, which Hamburg Ballet performed in Australia in 2012, it is absolutely compelling and arouses so many thoughts about the nature of Nijinsky—the man and the dancer. But, in contrast to the Neumeier work, the Cox film is almost serene in its overall mood, despite some confronting and bloody images relating to Nijinsky’s vegetarianism, and the challenging words and ideas spoken forcefully by Jacobi. That I find the mood serene is is not to suggest, however, that Cox has not presented the drama and the confusion of thought that permeated Nijinsky’s life. It is just felt in a different manner. The film and the dance work complement each other in a very unusual way and, having at last seen the film, I look forward immensely to seeing the Neumeier work again when it is performed by the Australian Ballet later this year.

Michelle Potter, 25 June 2016

Featured image: Vaslav Nijinsky as Petrushka. Photographer and source unknown

1. Joan Acocella, in her introduction to the unexpurgated edition of the diaries, published in English in 1999 as The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky, explains in detail how Romola altered the diaries in that first publishing endeavour of 1936. In particular Acocella notes that around 40% of the contents of the diaries was omitted. Acocella’s introduction is, as is all her writing, lucid and informed: Joan Acocella (ed.), The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1999).

2. Philip Tyndall describes the development of the film saying that Cox ‘did much of the cinematography himself in addition to the writing, directing, co-producing and editing.’ Philip Tyndall, ‘The diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky. The culmination of a career.’ In Sense of Cinema. Issue 20, May 2002. Accessed 25 June 2016.

3. Ramsay Burt, ‘Alone in the world. Reflections on solos from 1919 by Vaslav Nijinsky and Mary Wigman’. In On Stage Alone. Soloists and the modern dance canon, eds Claudia Gitelman and Barbara Palfy (Gainesville FL: University of Florida Press, 2012).

Dear Michelle,

I came across you whilst researching Vaslav Nijinsky, for a project I’m working on for my MA in Contemporary Art Practice. I just wanted to thank you for leading me to the Paul Cox film which I was previously unaware of.

Having read the Nijinsky’s diaries and finding them inspirational, I am presently downloading the film and very much looking forward to viewing it.

Best wishes,

Derek Dickinson

Thanks Derek for your comment. I hope you enjoy watching the film. I went back to read my post and was reminded of the approach Cox took, and of how much I loved watching the film.

On another point I went to your website and enjoyed looking at your gallery. I especially liked the Yves Klein-coloured works.

Dear Michelle,

thank you so much for taking the time to respond and to check out my website, it’s always great to get positive feedback. I haven’t finished watching the film yet but so far I am really enjoying it. I particularly like Derek Jacobi so it is a bonus hearing his narration. I do think the film will help enormously with my research, so once again thank you for guiding me towards it!

Best wishes,

Derek