10 February 2017, Tate Modern, London

The Robert Rauschenberg retrospective currently showing at London’s Tate Modern until 2 April, is a remarkable exhibition. It brims with the known from Rauschenberg—Monogram, the famous Angora goat with tyre; Bed made from a quilt when Rauschenberg had no money for canvas; the early Black Mountain experiments; the fascinating sound assemblage, Oracle; his silk screen work; in fact memorable items from every decade of his working life.

Combine: oil, paper, fabric, printed reproductions, metal, wood, rubber shoe-heel, and tennis ball on two conjoined canvases with oil on taxidermied Angora goat with brass plaque and rubber tire on wood platform mounted on four casters, 106.7 x 135.2 x 163.8 cm

Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Purchase with contribution from Moderna Museets Vänner/The Friends of Moderna Museet

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York

But it also has some fascinating lesser known items. They include a collection of personal boxes (Scatole personali) of various shapes and sizes containing an assortment of small items (including dead insects, pebbles, dirt and sticks) made in response to reliquaries Rauschenberg saw in the 1950s while touring Italy with fellow artist Cy Twombly; and a large, square, open-topped tank of bubbling mud, or actually bentonite clay and water, that is linked up with a sound system that records the sound of the bubbles plopping and spluttering.

What the exhibition shows quite clearly is that Rauschenberg was fearless in his approach to what constitutes art. He experimented with everything that came his way.

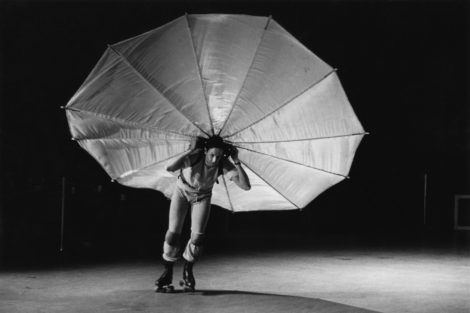

But I was especially interested in Rauschenberg’s collaborations with choreographers, including Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown and a range of choreographers working with Judson Dance Theater, and also with his own endeavours in the field of performance art. These activities were nicely represented in the exhibition with video material, photographs and, in the case of Rauschenberg’s performance pieces, his workbooks in which he recorded his movement ideas. Of his own pieces, the best documented was Pelican first made in 1963 for Rauschenberg himself, Per Olof Ultvedt and Carolyn Brown.

Photo: © Peter Moore © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

As video footage in the exhibition shows, Rauschenberg and Ultvedt performed the choreography on roller skates with parachutes attached to their backs and Carolyn Brown executed some balletic moves, including a stunning series of posé turns on pointe. The piece evolved when Rauschenberg was inadvertently described as choreographer rather than stage manager on publicity material for the Pop Art Festival being held in Washington D.C. in 1963. He seized the moment and made Pelican. Others of Rauschenberg’s performance pieces that were well documented in the exhibition included Elgin Tie and Spring Training.

Other dance material on show included some footage from Minutiae, an early work from Cunningham featuring a screen designed by Rauschenberg. While the screen itself was not included in the exhibition, the footage showed several close-up shots of it, including a small revolving mirror and pieces of lace and other fabric, in addition to the largely red paintwork. What was especially interesting was the location of the footage in a room of Rauschenberg’s ‘red’ paintings, made in a period when he moved away from his early experiments with black and white paint. These red paintings, which included Charlene (1954), a stunning work from the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, clearly set the context for the Minutiae screen.

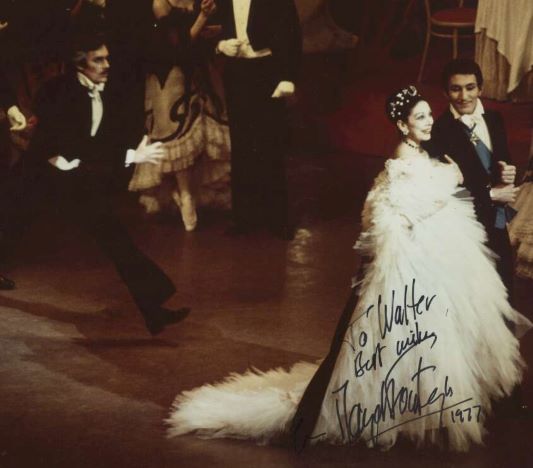

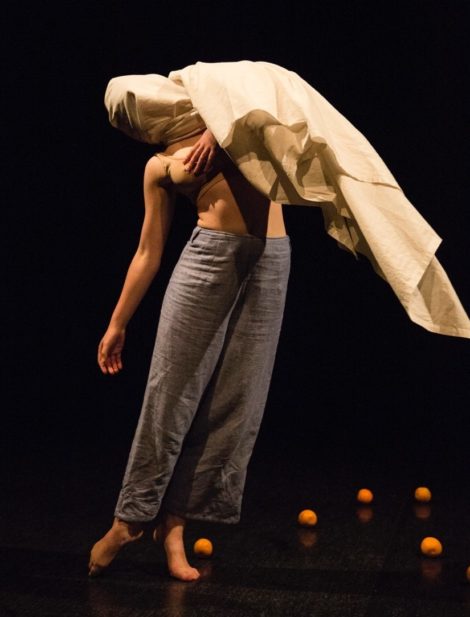

Other dance footage included a section from Cunningham’s Travelogue, designed by Rauschenberg in 1977. Again the location of the footage within the exhibition was significant. It provided further context for Rauschenberg’s Travelogue designs. In 1975 Rauschenberg spent time in Ahmedabad, a city in India renown for its textiles, and his use of textiles in his works from this period were hung in one room of the exhibition, along with the Travelogue footage. In Travelogue, this Indian experience is reflected in the costumes he designed, with their ‘wheels’ made from sections of different fabric; in the sheer cloth that hung from overhead as the dance progressed; and in the long strip of sheer, white fabric that the dancers carried at various stages.

On the other hand, the painting Charlene from 1954 has, in one corner of the canvas, a flattened-out umbrella with its sections painted in different colours and his Travelogue costumes are redolent of this part of Charlene. In fact, I was surprised by the extent to which umbrellas and parachutes appeared throughout the exhibition. They seemed to permeate most periods of Rauschenberg’s output.

Solvent transfer and acrylic on wood panel, with umbrellas

188.6 x 245.7 x 88.9 cm

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York

Then the exhibition also had on display material relating to Trisha Brown’s 1979 Glacial Decoy, for which Rauschenberg provided costume designs that required the use of sheer, white materials. He also provided the set, which consisted largely of a series of his photographs that were projected in a particular rotation onto four screens at the back of the stage space as the dance unfolded. There was video footage of Glacial Decoy for visitors to view and also, projected onto an exhibition wall in the manner in which they appeared on stage, were the photographs that made up the set.

One other item (or two items) interested me—Factum I and Factum II. These two works (combines) were painted simultaneously in 1957. Rauschenberg apparently said he made them because he was interested in ‘the role that accident played in my work’. They reminded me of those ‘spot the difference’ games, and the differences included drips of paint in one that were not the same in the other. But given the date at which they were painted—a time when Rauschenberg was closely involved with Cunningham and John Cage—that interest in ‘accident’ in a work must surely reflect the influence of Cunningham and Cage.

This was an exceptional exhibition, curated jointly by curators from Tate Modern and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. It was a great insight into the long and varied career of one of the world’s boldest artists, and there was much to be enjoyed for those whose major interest is in dance and collaboration.

Michelle Potter, 12 February 2017

Featured image: Costume from Travelogue (detail) as displayed in the exhibition INVENTION: Merce Cunningham and Collaborators, Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center, New York, 2007. Photo: © Neville Potter