22 June 2024 (matinee). The Playhouse, Queensland Performing Arts Centre, Brisbane

I didn’t see Greg Horsman’s version of Coppélia, a joint production between Queensland Ballet and West Australian Ballet, when it was first performed back in 2014. But, having admired his reimagining of La Bayadère (despite efforts by some to remove it, and other productions of Bayadère, from the world-wide repertoire), I was looking forward to Queensland Ballet’s presentation of Horsman’s Coppélia. I was not disappointed.

Horsman has kept enough of the original storyline of Coppélia so that the work is recognisable to those of us who have been brought up on the traditional version. Dr Coppélius is bent on bringing a doll to life while the people of the town try to discover what is happening inside his house. And there is the usual love interest wending its way through the story. But Horsman has set this Coppélia in South Australia, in the small town of Hahndorf, which was the home in the early 1800s of German settlers.

But before Act I begins, with its presentation of the activities of the Hahndorf townsfolk, we are given some background in an outstanding prelude. It introduces us to Dr Coppélius and his daughter Coppélia as they prepare to set out on a journey to settle in Australia. The prelude contains a brief moment on stage and then some film (stills and footage) as the boat traverses the oceans. As the voyage continues we see Coppélia’s death and her burial at sea.

The scene then moves to Hahndorf and follows the story largely as we know it, with some exceptions and additions. A notable addition is a brief, moving moment when we see Dr Coppélius (D’Arcy Brazier) making the decision to try to return Coppélia to life. Then there are changes to how the music is used choreographically. The Mazurka from Act I becomes a celebration of a recent win by Hahndorf’s football team. Later, parts of the music for the Czardas in Act I become an accompaniment to a German-style dance with lots of slapping of the knees.

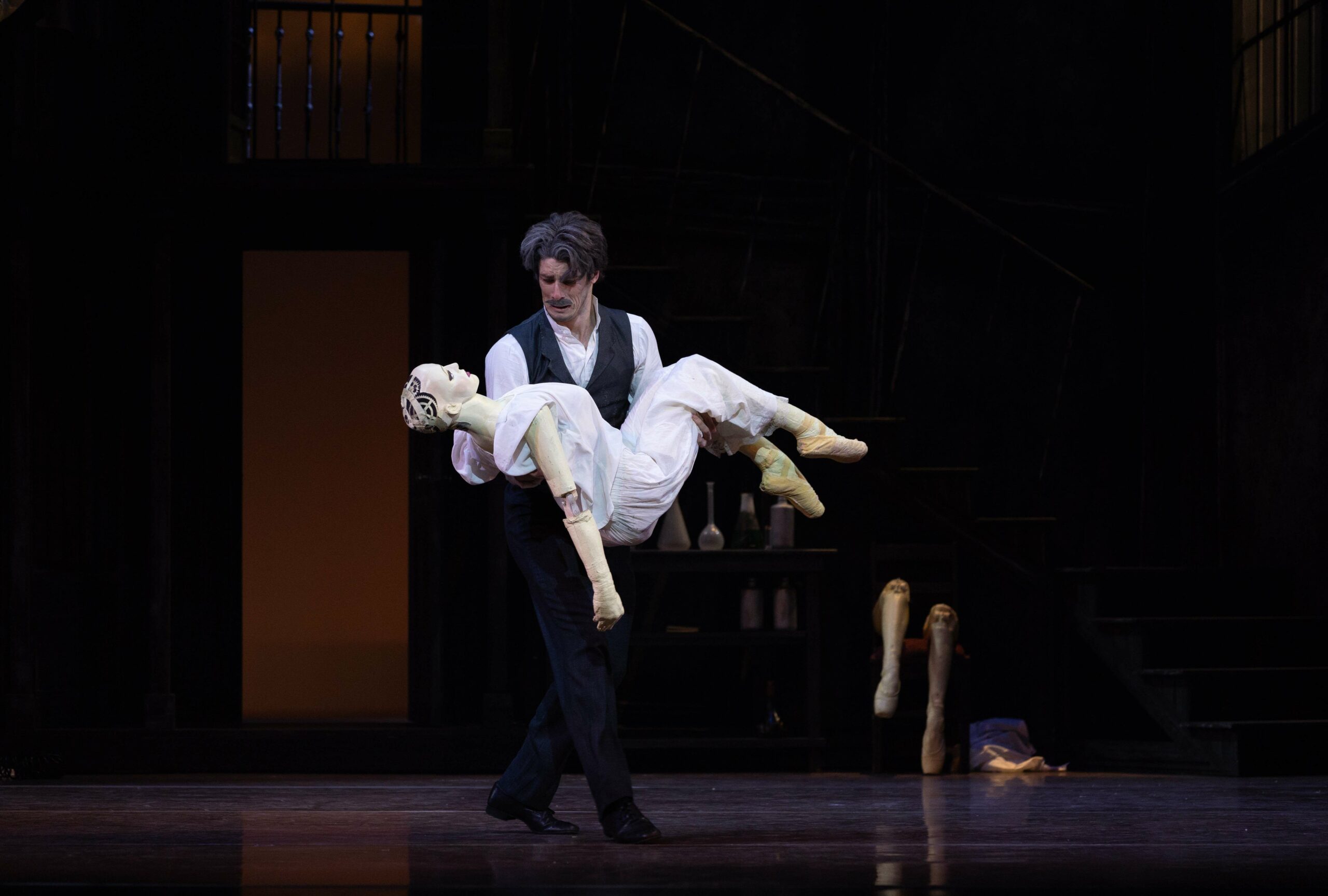

Act II keeps closely to the traditional production as Swanilda (Laura Tosar) and her friends discover the studio of Dr Coppélius, and Franz (Edison Manuel) climbs through a window in Dr Coppélius’ house to make his own discoveries. Act II ends as we might expect with Swanilda and Franz escaping while Dr Coppélius is left holding the doll he was hoping would be his daughter brought to life.

Act III adds some developments to the original story, including the appearance of an angry Dr Coppélius, who usually does not appear in this last Act, carrying his lifeless doll. But after a scuffle or two peace is reached between him and the townsfolk. Swanilda and Franz make plans for the future and the work ends happily.

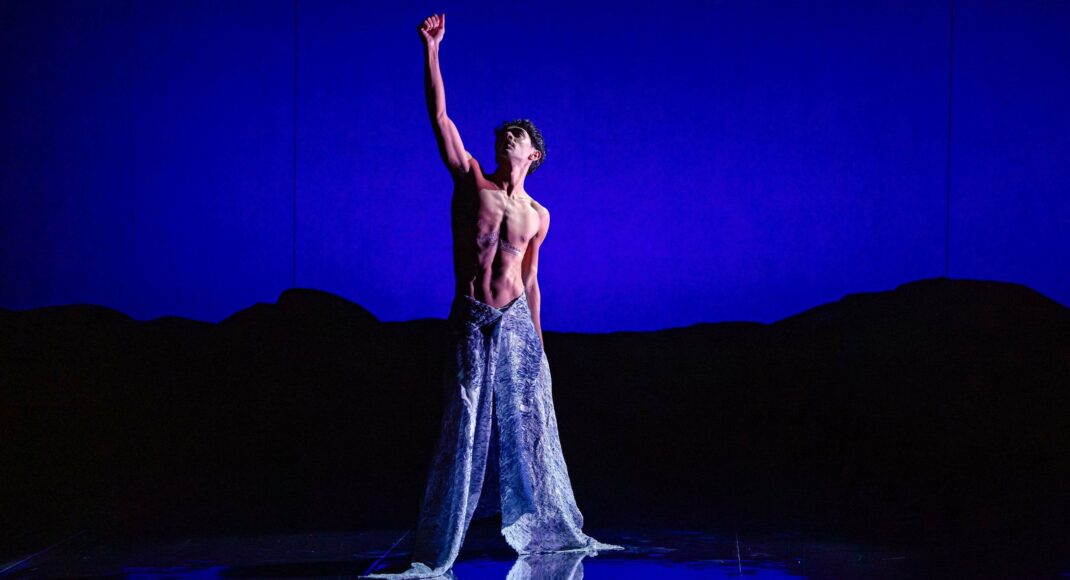

I was at the second last performance of this Coppélia and, as often happens in such situations. it is not always principal artists who take on leading roles. In particular, I enjoyed immensely seeing company artist Edison Manuel dance Franz. He was engaging in his characterisation and displayed a nicely placed and developed technique. He is someone to watch over the coming years.

There was so much to like in Horsman’s Coppélia. It was appealing in design with lighting by Jon Buswell, set design by Hugh Colman, and costumes by Noelene Hill. But what I especially loved was the way Dr Coppélius had been transformed. Gone was the bumbling, eccentric pantomime-style character that we so often see in traditional productions. Horsman’s Dr Coppélius was a man whose life had been rocked by the death of his daughter and we could see in his every move that he was not the eccentric person of the traditional ballet but someone whose emotions are like our own.

Some of the best choreographers in Australia and overseas have reimagined old stories and made them more relevant in some way. Greg Horsman has joined them and created a thoroughly enjoyable ballet with a coherent, Australianised storyline.

Michelle Potter, 26 June 2024

Featured image: Dr Coppélius and the doll he hoped he could bring to life. Queensland Ballet, 2024. Photo: © David Kelly