John Neumeier choreographer. Hamburg Ballet

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

John Neumeier has been the artistic director and choreographer of Hamburg Ballet since 1973. His prolific output of numerous full-length ballets over those decades is legendary, and what’s more, all the works have stayed current in the company’s repertoire and are given regular return seasons. That is a phenomenal achievement in world ballet terms.

I was more than fortunate, when on a Goethe Institut study tour to Germany in 2005, to see many of Neumeier’s full-length ballets staged in a breathtaking single week in Hamburg—Romeo & Juliet, Lady of the Camelias, Death in Venice, Midsummer Nights Dream, Odysseus, Mahler Third Symphony. I have simply never recovered from that week and indeed have no intention of ever recovering.

Hamburg Ballet later performed in Brisbane where I saw Nijinsky Gala. Neumeier has long and often cited Vaslav Nijinsky as the formative inspiration for his own life in ballet. On a later visit to Copenhagen I was enormously impressed by the Royal Danish Ballet’s production of The Little Mermaid, which they had commissioned of Neumeier. I visited Hamburg again in 2015, to see his Bach St.Matthew Passion.

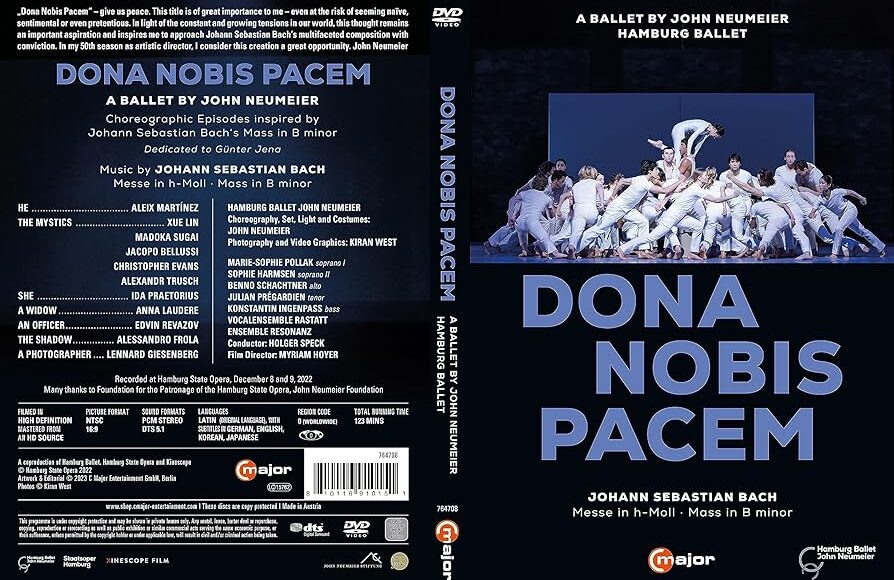

I’d have to say deep and lasting gratitude was the word for all these choreographic riches, but you can’t have too much of a good thing so when recently I noticed Dona Nobis Pacem, to JS Bach’s B Minor Mass, was to be Neumeier’s prayer for peace in the world and his swan song choreography as he prepares to retire from Hamburg Ballet, I was tempted to treat myself to a final trip to Europe. Would I, wouldn’t I get there?

Measure my delight then to notice that the local Arts TV channel was about to screen film of Dona Nobis Pacem right here in my front room! So I didn’t have to fly to Europe after all but just to cancel all commitments for a day and a night and sit glued to the screen for two airings of the work that proves among the of most poignant, exquisite, sad and uplifting of ballets ever made.

Do check Youtube for a 5 minute excerpt of the work. There you will see the superb ensemble dancing of the blessed spirits, as well as of the shell-shocked soldier-victims of war. The lead performer, Spanish born dancer Aleix Martinez, brilliantly portrays the central role of—shall we call him the Unknown Soldier, or Everyman. He would and should outdance warmongers everywhere—but that’s not the way the world works of course.

A few days later the same Arts Channel broadcast the documentary—The Life and Work of John Neumeier. All manner of insights are offered, as to how the boy from Milwaukee ended up as arguably Europe’s finest ballet choreographer who rates the music he selects as highly as the dances he sets to them. You don’t work with French pianist David Fray unless you mean business. Clearly these films exist somewhere in the world. Please hunt them down and watch them, then tell your grandchildren what you saw.

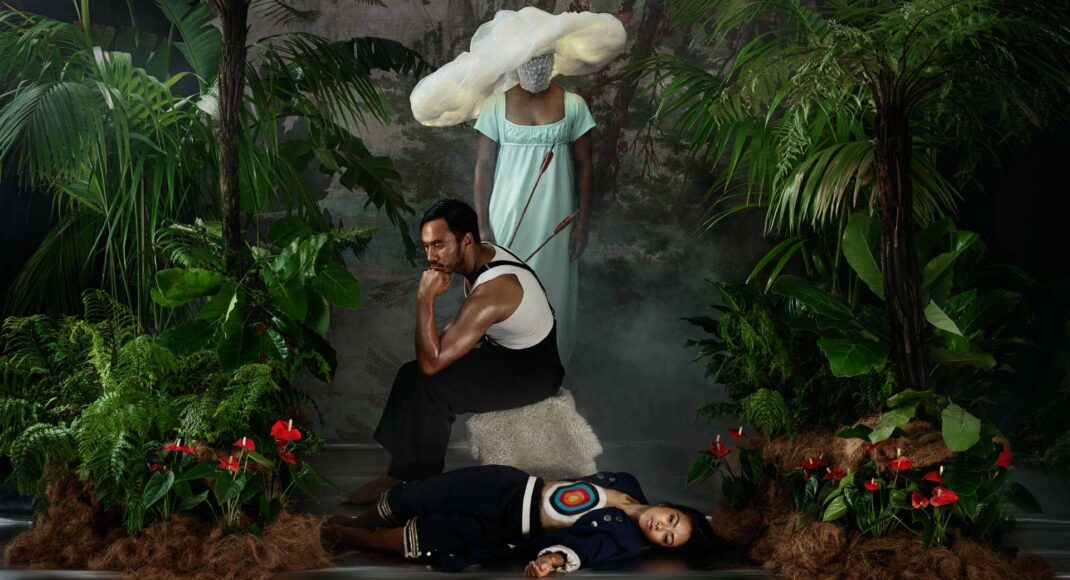

If we had to pick our three favourite choreographers in the whole world, and thank goodness we don’t, my votes would go to John Neumeier, and to New Zealand’s Gray Veredon (more on him later), and the remarkable Douglas Wright. Both Neumeier and Wright shared the magnetic inspiration of Nijinsky, of dancer and of choreographer in their own calling, and I was more than once made mindful of Wright by this choreography of Neumeier and by the performance of Martinez, which is about the finest compliment I can offer to them all.

Jennifer Shennan, 29 April 2024

Featured image: DVD cover, Dona Nobis Pacem