24 February 2024. Te Raukura, Kapiti

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The two recently appointed directors at RNZB, Tobias Perkins and Ty King-Wall, express in the program’s introduction their hope that the national Tutus on Tour production will leave the audience captivated, moved and wanting more. It did and we do.

The program opens with a set of excerpts from Swan Lake, staged after Russell Kerr’s treasured production from 1996. Usually we see either the complete four act ballet (which RNZB will perform in May this year), or just Act II as a stand-alone piece. Here however is a totally new experience—the full four acts reduced to a 40 minute abridged version, so it’s the classic story but without the trimmings, and on a tiny budget. Far from reducing the impact of the mighty original, this in an unexpected way brings out a poignancy and intimacy in the interactions between the characters, in what is effectively a chamber version of the choreography. And with soloists of this calibre, we lose nothing of the quality.

Turid Revfeim has staged the piece with care—but she swiftly credits David McAllister (who has been Interim Artistic Director at RNZB this past year) with the actual choice and sequence of excerpts. There’s no von Rothbart on stage for example but his evil presence is caught in the orchestral overture (in very good amplification in this excellent venue). The performance is danced to a 2013 recording of Nigel Gaynor conducting the NZSO, back in that memorable era when RNZB retained their own conductor on the staff, and he’d be the best ballet conductor, music advisor and arranger that you could want. We’re off to a very good start indeed, bathing in sumptuous Tchaikovsky.

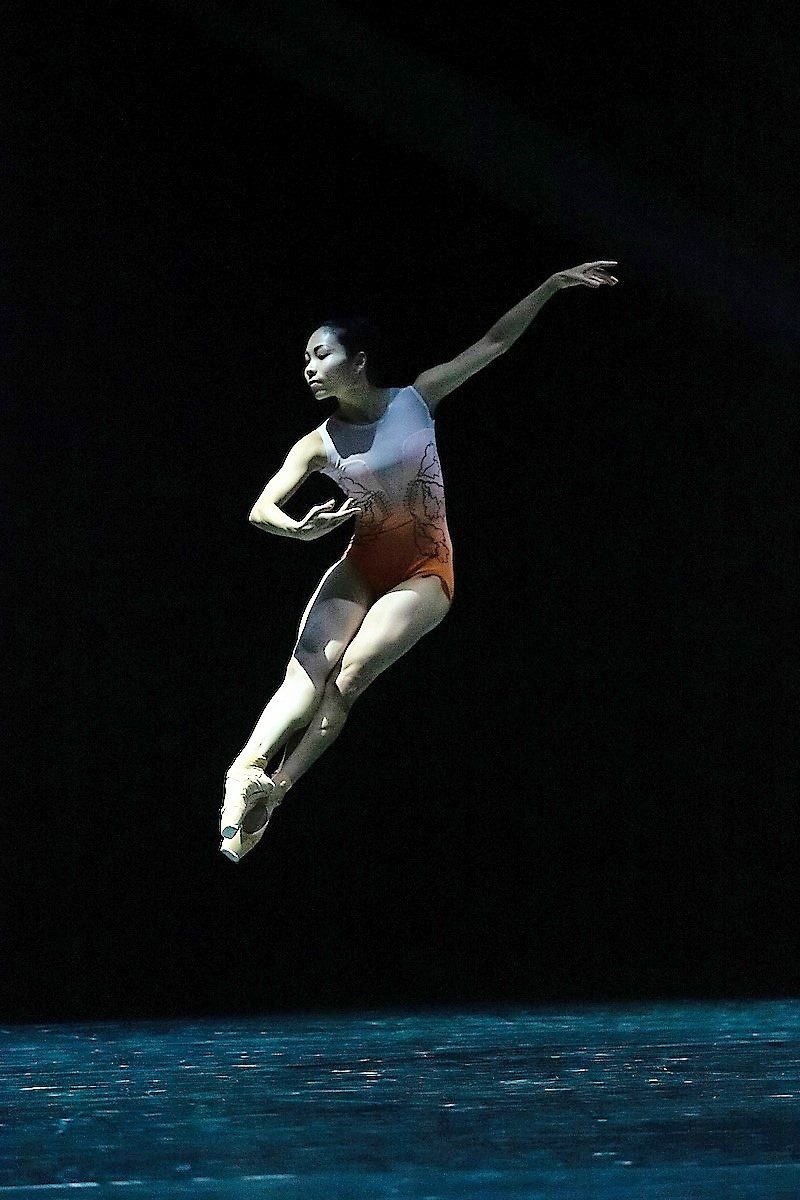

The cygnets are the pert little favourites and do very well. Laurynas Vejalis, a brooding Siegfried, dances powerful allegro legwork with adagio arms (that’s a whole lot harder to do than it sounds, and the results affect our pulse and breathing). Then he and Mayu Tanigaito as Odette develop an exquisite rapport in the pas de deux from Act II. This was a revelation and may have to do with the smaller proportions of the venue? In a full-sized theatre all the dancers have to project a larger-than-life scale to reach the back of the Gods. Here there’s little distance from stage to audience and that means the pair can dance solely to, with and for each other. Neither of them looks at the audience, we are merely voyeurs of their love-making. I’ve never seen anything quite like it.

There’s a charming pas de trois danced by Calum Gray, Catarina Estévez Collins and Cadence Barrack. Calum has a new strength and presence which is a pleasure to see. Then follows a smashing Neopolitan number by Ema Takahashi and Dane Head that sizzles the stage. Wow.

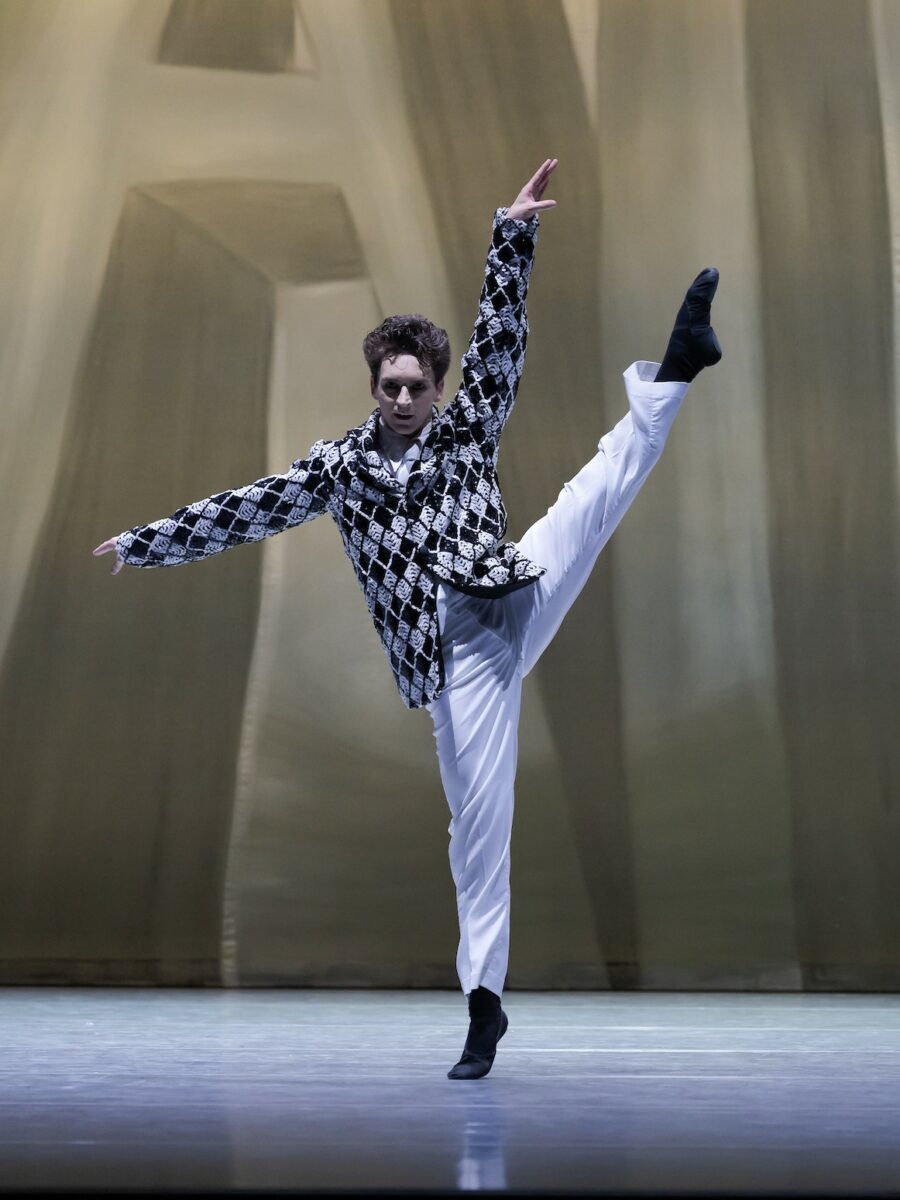

There’s a new Siegfried now, the sharp and spirited Kihiro Kusukami, to dance with Odile, Katherine Minor—and here’s another triumph, again I think in part due to the intimate scale of the venue. Siegfried looks only at his ‘love’ (but it’s ‘the wrong woman’, you fool), while she, the beautiful brazen two-faced prostitute, looks at him just often enough to keep him mesmerised, but also at times at us, not with a smile exactly, more of a sneer and a wink, as if to say ‘Aren’t I clever to seduce a prince like this and do my father’s bidding at the same time?’ It’s a very skilled performance indeed, and cadences a miniature ballet we will long remember.

After the interval comes Alice Topp’s Clay, a pas de deux from her Logos, to music by Einaudi, seen here in 2023. Performed by Mayu Tanigaito and Levi Teachout, this is in extreme contrast of movement style and vocabulary from the previous work and Mayu reveals the great range of her performing ability. With tightly focussed tension, the drama of their pas de deux recalls the choreography of the full work.

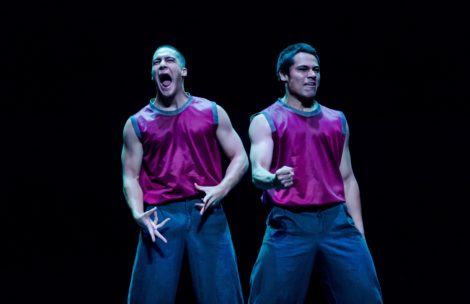

Shaun James Kelly has re-worked Prismatic (from the larger cast first seen in last year’s Platinum season). The bright and energised piece pays homage to the neo-classical gem, Prismatic Variations, co-choregraphed by Russell Kerr and Poul Gnatt in 1959. The ascetic aura of that talisman work cannot be easily imitated, but I do wonder if the dancers’ facial expressions and smiles could be reined in and at least in parts replaced by the meditative neutrality that gave the original work such a celestial aura and mana. There are striking sequences and shapes throughout the choreography, with a final triumphant sculpture of the group of twelve dancers that suggests the crow’s nest or bowsprit of a ship sailing on the high seas.

I very much value the printed program for its thoughtful and detailed content. The Company is entering a new era, and one can only wish them all safe travels and happy dancing in this tour around the country. Half the Company does the North and half the South Island, which gives valuable access for younger dancers to try new roles. Audiences in twelve centres will be thrilled to have them back. Some in those audiences will remember the tours of 156 towns that Poul Gnatt took New Zealand Ballet to in 1950s. He persuaded them to enrol as Friends of the Ballet and their 5-shillings subs paid for the petrol to drive to the next town. The rest is history.

Jennifer Shennan, 26 February 2024

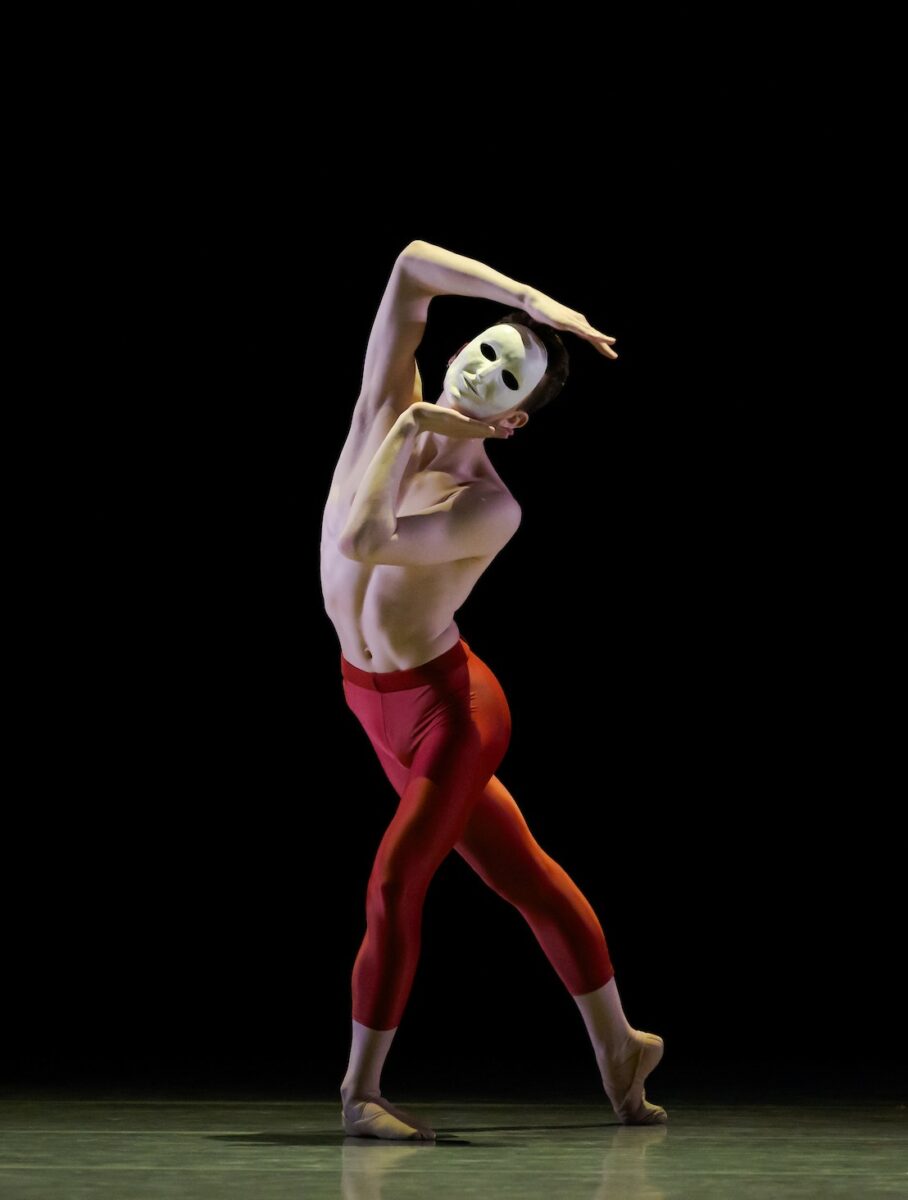

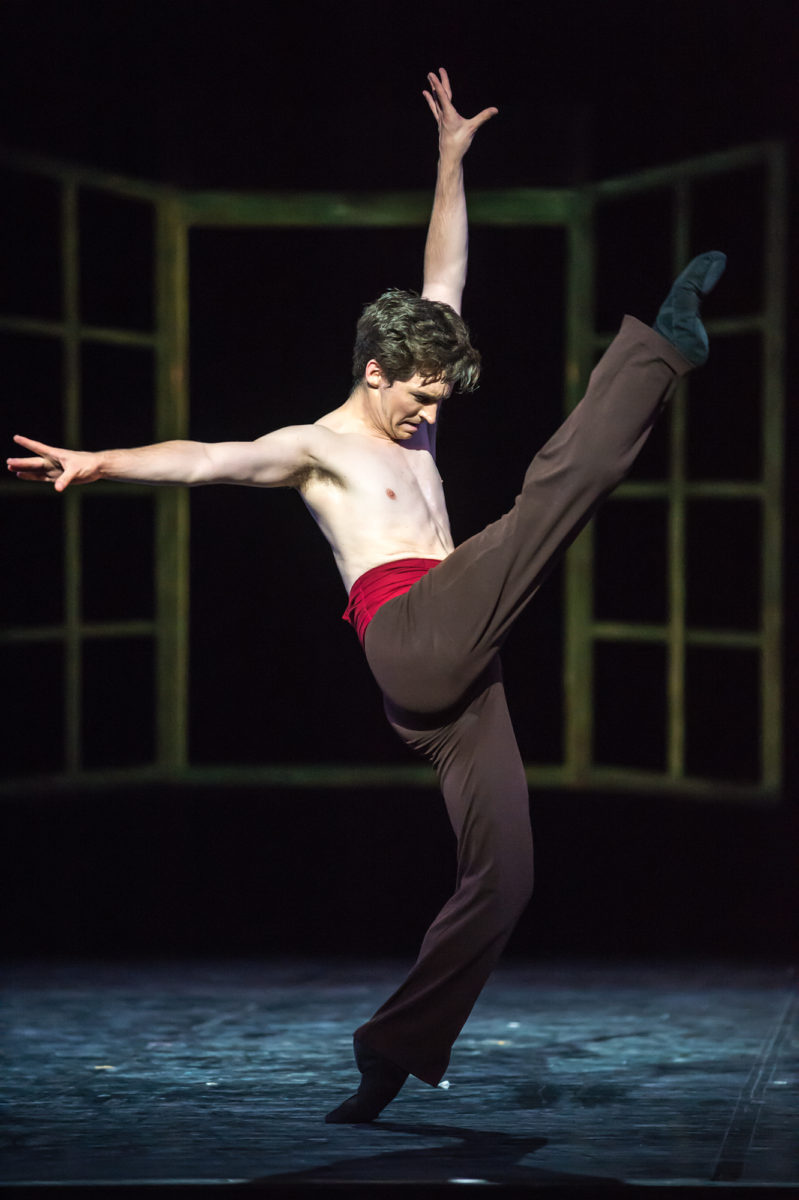

Featured image: Front cover image for the program for Tutus on Tour showing Mayu Tanigaito as Odile in Swan Lake. Photo: © Ross Brown