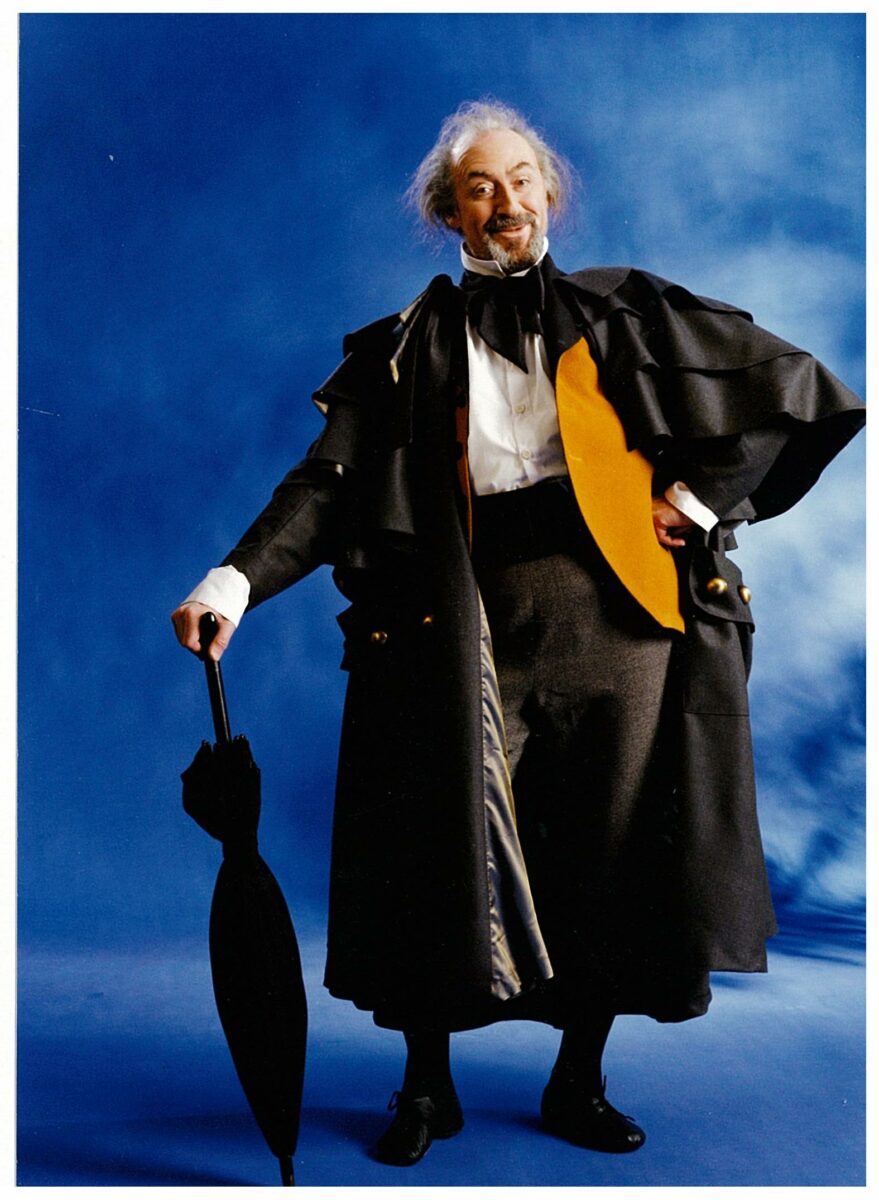

In Maori custom an address or oratory always opens with acknowledgment of those recently deceased, recognising ‘the mighty totara trees that have fallen.’ That puts Jon Trimmer right up there in the first line since he is/was unarguably the hero of New Zealand dance. Knighted for his unmatched artistry, and the longevity of his fabled performance career, Jon was loved by so many—for all the roles he danced but also for the plain common decency in the man. Fastidiously professional about his own work, he was always interested in the work of others, ever standing by to help should that be needed. Jon may have passed (26 October 2023, aged 84) but the memories of his mighty performance career will never be forgotten, never. Nor will we see his like again, ever. Jon carried the mantle from Poul Gnatt and Russell Kerr to safeguard the Company for decades. That now passes to those performers and directors who lead RNZBallet. One can only wish them courage. [The Company’s public tribute to Jon will be held in Wellington on Friday 2 February, 2024. See Company’s website for details and reservations. The next Russell Kerr lecture in Ballet & Related Arts, on Sunday 25 February 2024, will be devoted to Jon. Presenters include Turid Revfeim, Anne Rowse, Kerry-Anne Gilberd, Michelle Potter. For details and reservations, email jennifershennan@xtra.co.nz). Links to my obituaries for Jon are at this link and at www.stuff.co.nz

……………………

The Auckland Arts Festival began the year with two striking productions—Revisor, stunning dance-theatre choreographed by Crystal Pite, with dancers playing actors playing dancers. Scored in Silence was a deeply moving film-dance testament to the experiences of the profoundly deaf community of Hiroshima 1945.

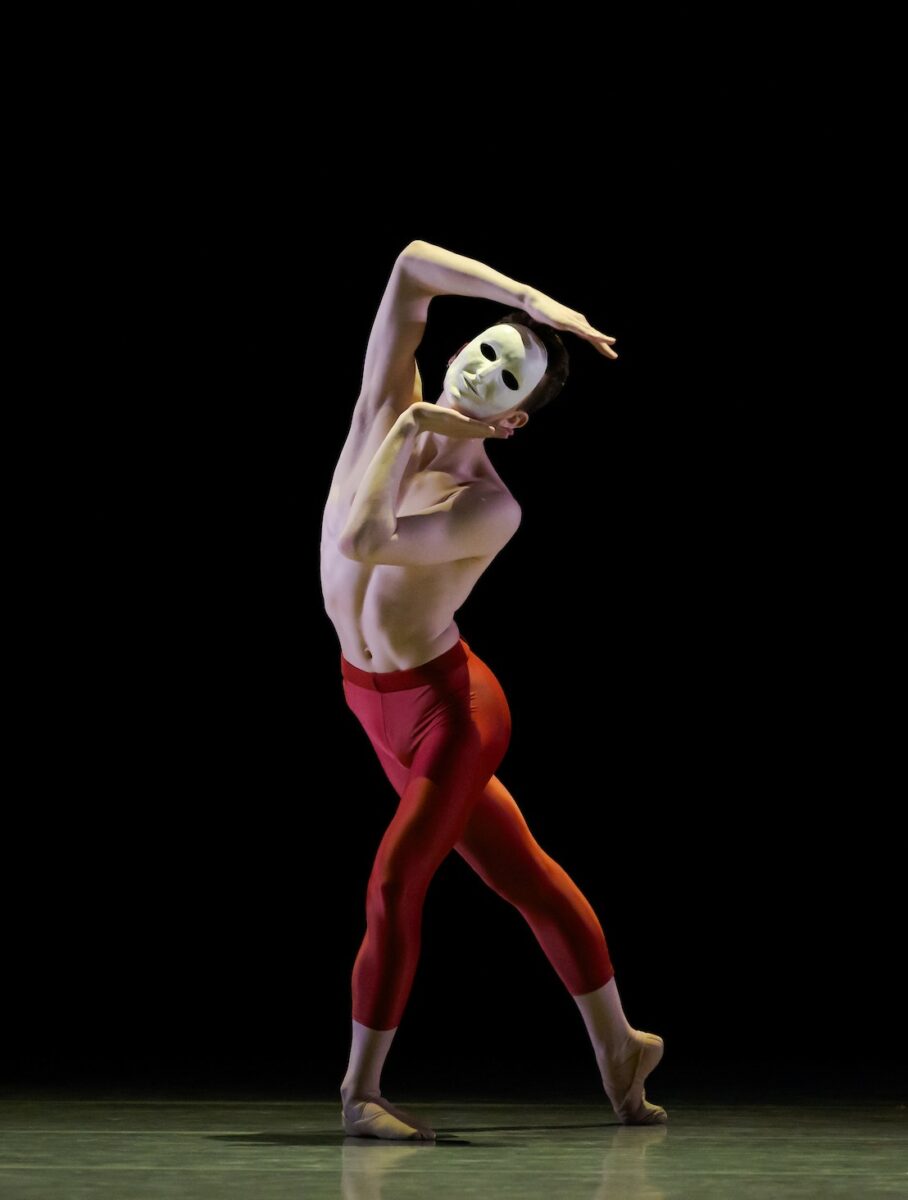

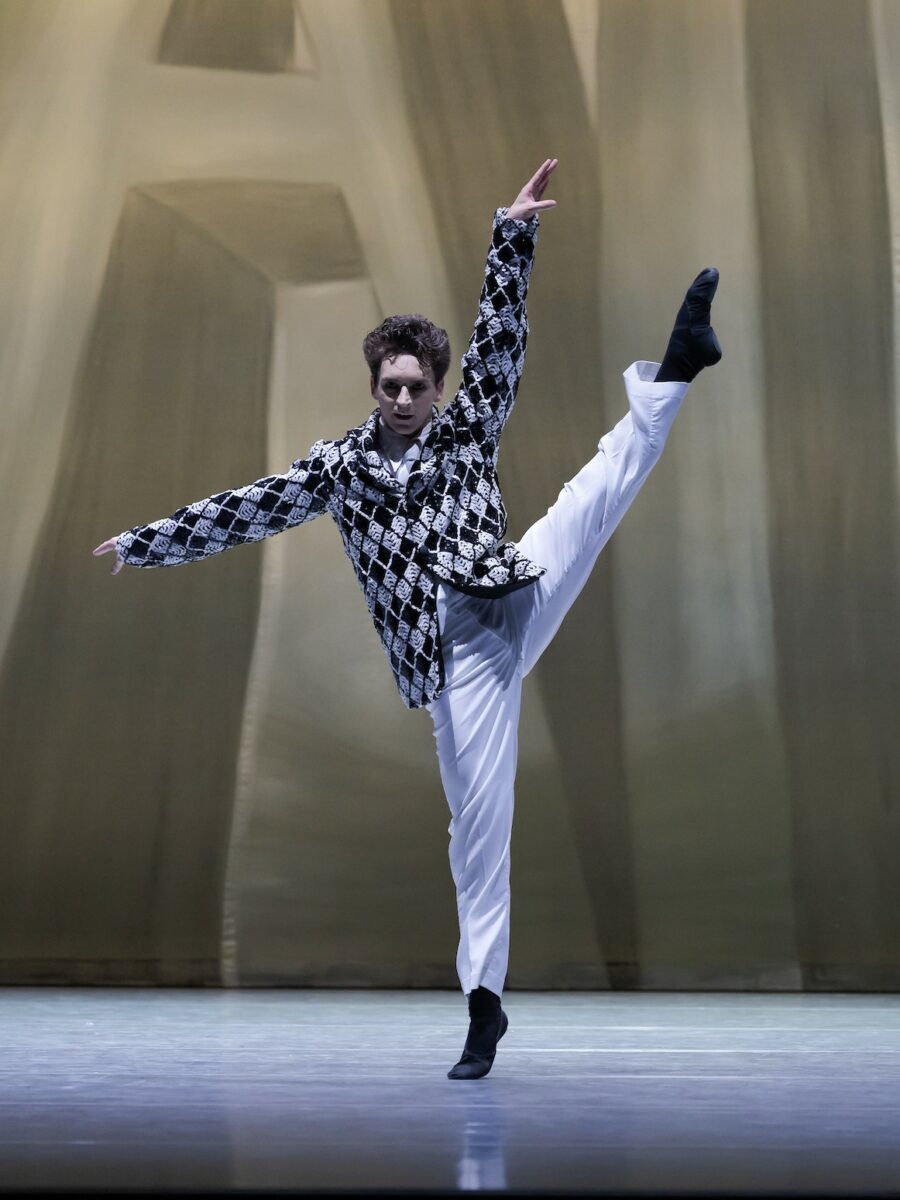

Royal New Zealand Ballet’s mid-year season Lightscapes, had four works with for me the standout Requiem for a Rose by Annabella Lopez-Orcha—a beautiful mysterious meditation, and the powerfully atmospheric Logos by Alice Topp (an RNZB alumna). Their single performance Platinum, was a tribute to 70 years achievement. My enduring memory is of Sara Garbowski dancing exquisitely in the excerpt from Giselle Act II. Sara has since retired from her 15 year performance career, and I for one am sorry we did not see her in the complete ballet. (Perhaps if she finds retirement over-rated she could come back as a guest artist to perform it in a year’s time?). The Company’s year ended with a romping return season of Loughlan Prior’s Hansel & Gretel which the rejuvenated company performed with great gusto.

Mary-Jane O’Reilly’s Ballet Noir, a contemporary treatment of Giselle Act II, was a phenomenal achievement—independent dancers who nevertheless performed as a seasoned company, with flawless technique, integrated design and powerful dramatic effect. We don’t do Dance Oscars, thank goodness, but if we did, this work would probably score. Another memorable season was the dance opera, (m)Orpheus, with direction and choreography by Neil Ieremia of Black Grace dance company. The dancers combined seamlessly with the singers who found nobility in a contemporary urban setting.

It was terrific to hear of Raewyn Hill’s staging Douglas Wright’s exquisite Gloria on her Co3 in Perth. Rumours of other works by Douglas in their planning for re-staging, mean I’d better be saving for an airfare. In Wellington an exhibition, Geist, of Tessa Ayling-Guhl’s photo portraits of Douglas Wright from 2015, was a moving experience. Björn Aslund choreographed a solo, geist dance, accompanied by Robert Oliver on bass viol, in the gallery. It’s always special when a dance enhances an art gallery space, uniting both art forms. A gathering was held at The Long Hall on October 14 to mark Douglas’ birthdate — and an archival screening of The Kiss Inside made compelling viewing. We plan to host a similar event every year on that date, and are grateful to Megan Adams who maintains the Douglas Wright archive with fastidious care.

A capacity audience attended the Russell Kerr lecture, this time focussing on Patricia Rianne’s celebrated career, and viewing her 1986 ballet, Bliss, based on the Katherine Mansfield short story. 2023 marks the centenary of Mansfield’s death and I was honoured to present a paper KM and Dance, at the VUW conference held to mark that.

2023 also marked the centenary of the tragic incident in which a young dancer, Phyllis Porter, was performing in the Opera House in Wellington, when her tarlatan skirt caught on the gaslight in the wings and she was horribly burnt, and died four days later. Shades of Emma Livry in Paris, though no-one here makes a pilgrimage to Phyllis’ resting place.

2023 offered several memorable dance videos—the Arts channel had a repeat screening of the splendid Cloudgate in Lin Hwai Min’s Rice. Firestarter about Bangarra Dance Theatre again made compelling viewing. A doco, The Boy Who Couldn’t Stop Dancing told of Tom Oakley, a young Liverpool boy with serious cystic fibrosis yet who had danced his way to win a scholarship to Rambert Dance school. The outstanding force in German dance, Susanne Linke, sent me an intriguing video of her dance project, Inner Suspension, in which she shares her pedagogy and technique. (Anyone interested to receive the link could email Inge Zysk at info@susannelinke.com).

Several dance books of interest featured in my year. David McAllister was appointed Interim Artistic Director at RNZBallet. His two books, Ballet Confidential and the earlier Solo, provide access to the backstage life of the ballet and proved popular among local readers. The book Royal New Zealand Ballet at Sixty which Anne Rowse and I co-edited back in 2013, was released in a digital edition by Victoria University Press.

If I had to signal the hour and a half of the year that offered the purest dance pleasure, it would be the RNZB Company class I observed taught by David McAllister. Clarity of physics, and the miracle of anatomy, combined with music and poetry from each dancer, reveals the art, unmarked by choreography, casting, costumes and champagne—all the things we go to the ballet for. Here by contrast is the forge and the chapel where the art of the dancer is daily honed and made good. It’s my favourite thing.

Season’s greetings to all—in happy anticipation of 2024 which will see Akram Khan’s The Jungle Book Reimagined—and mid- year an intriguing project, Bismaya, in which Chamber Music New Zealand are bringing musicians from India to combine with Vivek Kinra’s Mudra dance company in a national tour and workshops. Russell Kerr’s pedigree production of Swan Lake from RNZB comes up in May, and later their mixed bill, Solace which includes a new work by Alice Topp. A return season of Liam Scarlett’s magical Midsummer Nights’ Dream is the work that keeps his talent alive.

Jennifer Shennan, 30 December 2023

Featured image: Jon Trimmer as a Stepmother in Cinderella. Royal New Zealand Ballet, 1987. Photo courtesy Royal New Zealand Ballet