Book by Michelle Potter. Published by FortySouth Publishing, Tasmania

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The first word of appreciation for this book should go to its design and visual appeal. A well-made paperback volume of good weight and proportion, it feels right in the hand, and its pages stay open (instead of closing themselves as typical paperbacks annoyingly do). In addition the ink of the text sits bright on the page rather than being absorbed into the paper, so that by running your hand over the page you discover a kind of braille, a little dance for your fingertips, in a haptic pleasure I don’t recall noticing in other volumes (clever designer).

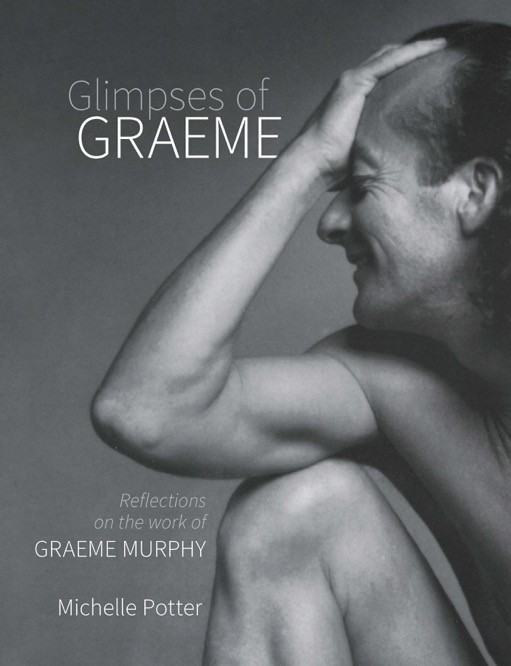

The front cover image is Murphy the man, in dance profile and grinning, the back cover Graeme the young schoolboy, smiling his pleasure for the ice cream sundae he has just enjoyed. The front endpaper has a curtain-call lineup of applause—the back endpaper has Murphy acknowledging that applause—with a facing image of Graeme and his life and work partner, Janet Vernon, back to back. Their combined lifetime contribution to dance in Australia receives tribute in every chapter of the book (heroic couple, generous author).

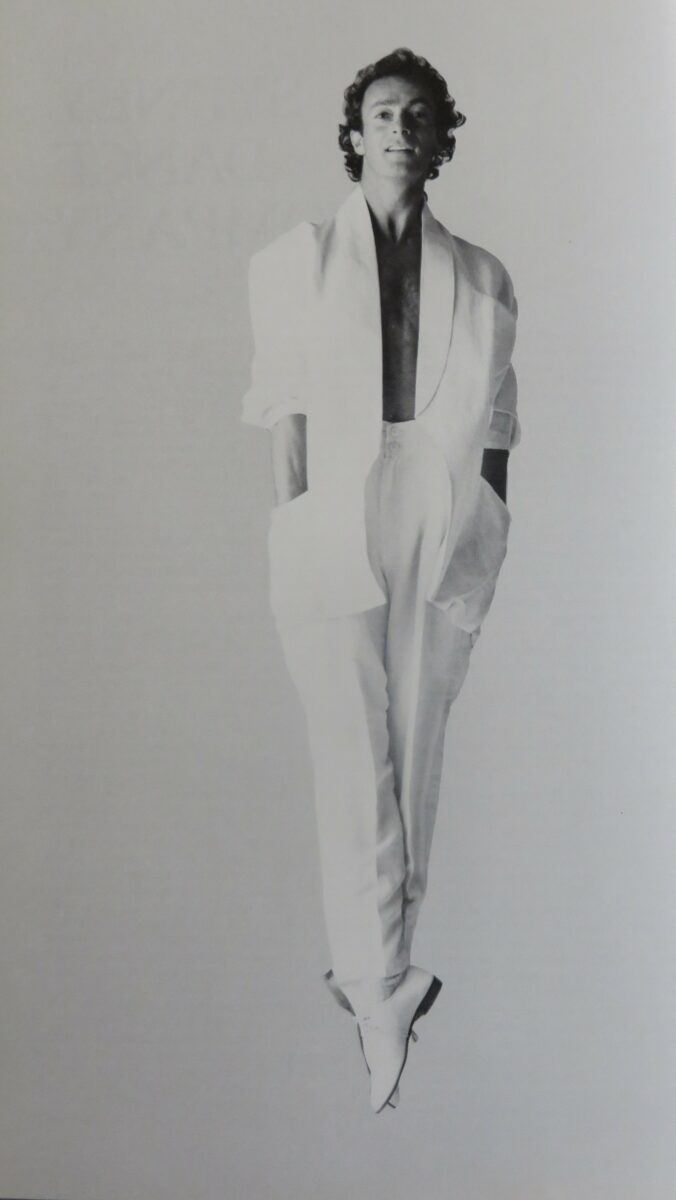

The frontispiece photo has Graeme Murphy en l’air, not in some balletic cliché of soaring jeté or flying leap, limbs outspread, striving beyond gravity, where aspiration replaces destination. This is not any role performed but the man himself, right here, right now, in the middle of the page, looking straight at you, the reader. Hello.

Simultaneous movement in both upward and downward directions is implied. The single vertical stroke of the svelte elevated dancer in white trousers and loose-lapelled jacket, legs pointing down with pencil sharp engaged feet in an exquisite fifth position displaying all the stylised turnout that ballet requires of a dancer, (but none of the distorted overarched eagle feet sometimes displayed by those more interested in virtuosity than in dialogue or eloquence). Meantime the upper body is that of a relaxed and graceful man, hands tucked into large pockets, an enigmatic smile hovering around his lips. The floor is not shown in the photo so the image is of a dancer enduringly airborne, not one ounce of the effort involved in an elevation of this order allowed to show. Dancing masters of the Italian Renaissance had a term for this quality—sprezzatura/‘divine nonchalance’—as though to say ‘Look—leaping like this is as easy as breathing. I’ll teach you how to do it if you like.’ Yeah right. It’s a graceful yet wonderfully cheeky portrait, inviting readers into the book (gifted dancer, clever photographer). I savoured the photo for a day before starting to read the text. Felt as though I had been dancing.

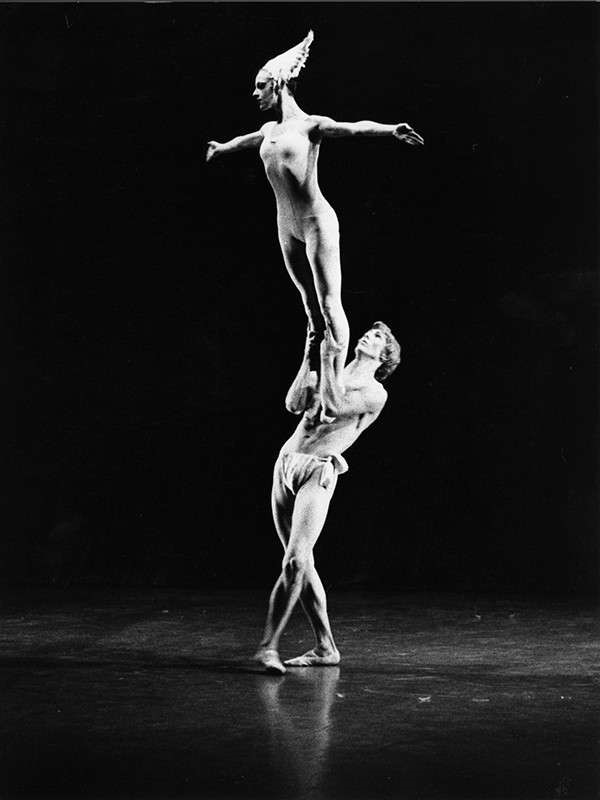

The book title is borrowed from Murphy’s first major choreography, Glimpses, 1976. The astonishing photograph from that work reveals his early theatrical vision, with Janet Vernon standing tall on the chest of dancer Ross Stretton.

Eight chapters celebrate Murphy’s choreographic works in thematic rather than chronological treatment, mainly through excerpts selected from reviews Michelle has written over the years. It has been a colossal choreographed body of work. Over and over Murphy’s collaborations with design artists and composers are acknowledged and there is much discussion of the Australian content within the works, by dint of those collaborations rather than simply in local narratives or settings.

I thoroughly enjoyed reminders of those of Murphy’s works we have seen in New Zealand — with design by Kristian Fredrikson, the striking Orpheus for the RNZBallet’s celebrated Stravinsky centenary season in 1982, devised by artistic director Harry Haythorne. Our company also staged The Protecting Veil the following decade. Sydney Dance Company visited with Shining (I recall a mighty performance from New Zealand dancer Alfred Williams). They returned with Some Rooms, a fine work which appealed to audiences wider than just dance aficionados. Berlin was a major work that well warranted the trip to Auckland then, so of interest now to learn of the creative processes of its music ( with Iva Davies and Icehouse) and design (by Andrew Carter).

I also saw Mythologia in Sydney, 2000, though I retain much livelier memories of the inspired Nutcracker, The Story of Clara, and of the remarkable Swan Lake for Australian Ballet. Harry Haythorne had roles in these two works, but it was his tap-dancing-on-roller-skates routine in Tivoli that warranted yet another trip across the Tasman, to see the hilariously entertaining yet simultaneously poignant production. The closing image has never left me.

It’s also a good memory that Murphy invited New Zealand choreographer Douglas Wright to stage his legendary Gloria, to Vivaldi, on Sydney Dance Company.

Once when I was visiting Harry in Melbourne, he took a phone call from Graeme and I recall a very long conversation, more than an hour, with loads of laughter while Harry winked and indicated I should continue browsing his bookshelf. They were clearly best of mates with a great deal of respect for each other’s work.

There’s another synergy one can appreciate: Graeme’s work, Grand, was made for and dedicated to his mother—and Michelle has made and dedicated this book to her own mother who died recently.

The book’s text is succinct and its themes clearly delineated. My paraphrasing would not be nearly as useful as my encouragement to you to find and enjoy it for yourself (lucky reader).

Jennifer Shennan, 19 November 2022

Featured image: Cover image (excerpt) of Glimpses of Graeme. Full cover reproduced below.